Ramsay Hunt Syndrome

Ramsay Hunt Syndrome (or herpes zoster oticus) is a shingles-type reactivation of varicella zoster virus infection affecting the seventh cranial nerve.

Ramsay Hunt Syndrome is a rare condition, far less common than Bell’s palsy. However, it is vital to diagnose as its consequences can be devastating.

The principal feature distinguishing it from the more benign Bell’s palsy is the presence of vesicular lesions characteristic of shingles. It is important to look for vesicles in any patient who presents with a presumed Bell’s palsy. A clue to its presence can be severe pain, often out of proportion to that seen in Bell’s palsy (where pain is generally mild or absent).

Ramsay Hunt Syndrome is treated with anti-herpes virus drugs.

The role of steroids in Bell’s palsy is well established; their role in Ramsay Hunt Syndrome is less certain, but they are still prescribed given the seriousness of the condition.

History

Ramsay Hunt Syndrome was named for American neurologist James Ramsay Hunt (1874–1937), who first described the condition in 1906.

Epidemiology

- Ramsay Hunt Syndrome is uncommon.

- More common in patients >60 years.

- Rare in children.

Anatomy

The facial nerve (seventh cranial nerve) has two components:

- The larger portion contains motor fibres stimulating the muscles of facial expression.

- The smaller portion contains:

- Taste fibres (anterior two-thirds of the tongue).

- Secretomotor fibres to the lacrimal and salivary glands.

- Some pain fibres.

Pathophysiology

Herpes zoster oticus (geniculate herpes), Ramsay Hunt Syndrome

- Infection occurs within the geniculate ganglion:

- Results in seventh cranial nerve involvement.

Cephalic Zoster, Ramsay Hunt Syndrome

- Infection occurs within the brainstem:

- Leads to polycranial neuropathy.

- Seventh cranial nerve involvement plus possible involvement of adjacent cranial nerves:

- 3rd, 4th, 6th cranial nerves.

- 5th cranial nerve.

- 8th cranial nerve.

- 9th cranial nerve.

- 10th cranial nerve.

Clinical Features

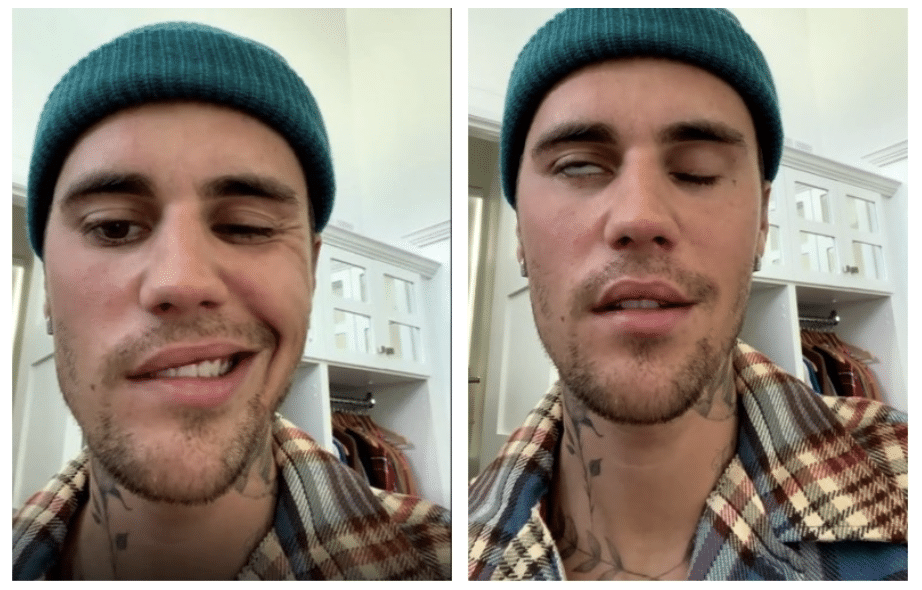

There is a unilateral lower motor neuron seventh cranial nerve palsy associated with ipsilateral vesicular lesions and pain.

1. Features of LMN seventh cranial nerve lesion

- Facial paralysis:

- Weakness/paralysis of entire face (upper and lower) on affected side.

- Assess voluntary movement of the upper face.

- Bell’s sign: eye may roll upward when attempting closure.

- Drooling.

- Loss of taste on anterior two-thirds of the tongue.

- Lacrimation.

- Subjective feeling of facial numbness (without true sensory loss).

2. Vesicles

- Vesicles seen in sensory distribution of the seventh nerve:

- External auditory canal.

- Auricle of the ear.

- Anterior two-thirds of tongue.

- Hard palate.

- Other cephalic vesicles may indicate brainstem involvement:

- Trigeminal nerve branches.

- Palate and pharynx (ninth and tenth nerves).

3. Vestibulocochlear nerve involvement

- Hearing impairment.

- Tinnitus.

- Vertigo.

4. Pain

- Otalgia is common and may precede both paralysis and vesicles (making early diagnosis difficult).

- Pain may be more widespread than in Bell’s palsy.

- Severe pain may be an important clue, as Bell’s palsy typically causes only mild or no pain.

Prognosis

- Worse prognosis than Bell’s palsy.

- Lower probability of complete recovery.

Investigations

Diagnosis is usually clinical, but the following may be considered:

Blood Tests

- FBE — WCC may be elevated.

- CRP — may be elevated.

Serology

- VZV serology usually reflects prior chickenpox and is generally unhelpful.

- Rising antibody titre is more useful.

PCR Testing

- VZV PCR on tear or vesicle fluid may confirm infection.

MRI

- Consider if diagnostic uncertainty or polycranial nerve involvement.

- MRI features:

- Increased enhancement of the facial nerve (similar to Bell’s palsy).

Management

1. Antiviral Therapy

- Most effective if started within 72 hours.

- Options:

- Acyclovir.

- Valaciclovir.

- Famciclovir.

- In severe cases (vertigo, tinnitus, hearing loss):

- Consider IV therapy initially, then transition to oral antivirals.

2. Steroids

- Clearly beneficial in Bell’s palsy.

- Less clear in Ramsay Hunt Syndrome, but expert consensus favours their use.

3. Supportive Measures

- Eye protection to prevent corneal complications.

4. Analgesia

- Provide analgesia as clinically indicated.

5. Psychological Support

- Many patients experience severe and distressing symptoms; psychological support is important.

Disposition

- All cases should be reviewed by neurology.

- Consider ophthalmology review if eye closure is impaired.

- Many cases are severe and may require hospital admission.

References

Publications

- Hunt JR. On herpetic inflammations of the geniculate ganglion. A new syndrome and its complications. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 1907;34:73–96

- Sullivan FM, Swan IR, Donnan PT, Morrison JM, Smith BH, McKinstry B, Davenport RJ, Vale LD, Clarkson JE, Hammersley V, Hayavi S, McAteer A, Stewart K, Daly F. Early treatment with prednisolone or acyclovir in Bell’s palsy. N Engl J Med. 2007 Oct 18;357(16):1598-607.

- Gagyor I, Madhok VB, Daly F, Somasundara D, Sullivan M, Gammie F, Sullivan F. Antiviral treatment for Bell’s palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Nov 9;(11):CD001869

- Sullivan F, Daly F, Gagyor I. Antiviral Agents Added to Corticosteroids for Early Treatment of Adults With Acute Idiopathic Facial Nerve Paralysis (Bell Palsy). JAMA. 2016 Aug 23-30;316(8):874-5.

FOAMed

- Cadogan M. James Ramsay Hunt. LITFL

Fellowship Notes

MBBCh Cardiff University School of Medicine. BSC (Hons) Medical Microbiology Leeds University. I am a current ED RMO at the Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital in Perth hoping to pursue a career in ENT surgery.

Educator, magister, munus exemplar, dicata in agro subitis medicina et discrimine cura | FFS |