RESCUEicp and the Eye of the Beholder

Guest post by Dr Alistair Nichol, Professor of Intensive Care at the Alfred Hospital and Monash University School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine.

Outcomes following decompressive craniectomy… “Favourable” is in the eye of the beholder!

The “Trial of Decompressive Craniectomy for Traumatic Intracranial Hypertension” (RESCUEicp) trial recently reported outcomes following decompressive craniectomy in 408 patients with severe Traumatic Brian Injury (TBI)1. This publication had been eagerly awaited after the Decompressive Craniectomy in Diffuse Traumatic Brain Injury (DECRA) study2 reported worse functional outcomes at 6 months following bifrontal decompressive craniectomy. In DECRA2 this worsening of outcomes occurred despite a significant reduction in ICP in patients who received a decompressive craniectomy2.

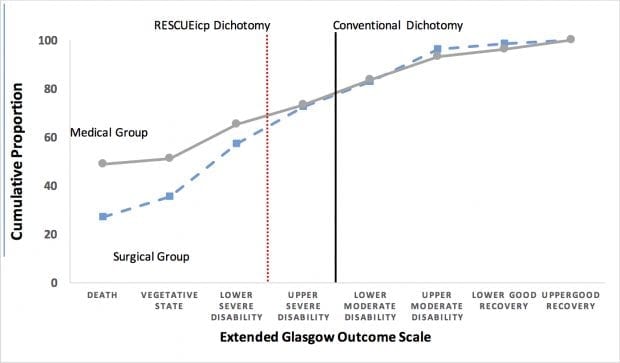

The inclusion criteria and the choice of surgical decompression differed somewhat between these two studies1,2. The RESCUEicp investigators reported a positive outcome with an increase in “the rate of an outcome of upper severe disability or better was 42.8% in the surgical group versus 34.6% in the medical group” 1. This reported finding might not be as straightforward to interpret as initially presented. While there are a number of scales available to assess outcome in patients after TBI3 the extended Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOSe) is the most commonly utilised. The conventional assessment of outcome after TBI has defined as “favourable” if there is full independence at 6 months (GOSe grade 5-8) and unfavourable ((GOSe grade 1-4) if there is death or severe disability.

The dichotomized reporting of patients as having “favourable” or “unfavourable” outcomes depends upon the “dichotomization point” chosen. The RESCUEicp investigators chose a non-conventional dichotomization point and rated GOSe grade 1-3 as “unfavourable” and 4-8 as “favourable”. Significant caution is needed when established scales are modified or when new points of dichotomization are used to convey long understood meanings. Under this new interpretation, favourable outcomes would not now indicate fully independent but only the ability to be left alone at home for at least 8 hours per day with an ongoing need for assistance outside the home. Indeed, there may be merit in looking at a new dichotomization point in an old scale. However, this change of meaning has an enormous impact on individuals and families and the socio-economic impact of what a favourable outcome is and is only apparent after a more considered read!

Furthermore, if we shift the dichotomization point back to the conventional definition GOSE grade 5-8 the reported benefits are no longer apparent (see Figure 1). In a recent letter to the NEJM we (J Cooper, A Nichol, C Hodgson), commented that the proportion of patients with the conventional “favourable” outcomes were now exactly 27% in medical and surgical groups, as compared to the reported 32.4% in medical and 45.4 surgical groups (p=0.01) using the RESCUEicp dichotomization4.

Whether this treatment is perceived as effective or not depends on both the dichotomization point chosen (Figure 1) and our definition of what is a “favourable” outcome for a patient. Convention would say decompressive craniectomy is NOT an effective intervention.

Clinicians should consider these nuances before advocating for a decompressive craniectomy for their patients.

Figure 1. Cumulative Proportions of Results on the Extended Glasgow Outcome Scale. The cumulative proportion is the percentage of all scores that are lower than the given score. Conventionally, an unfavourable outcome is defined as a composite of death, vegetative state, or severe disability (Upper and Lower), corresponding to a score of 1 to 4 on the Extended Glasgow Outcome Scale, as indicated by the solid vertical line. The RESCUEicp study defined an unfavourable outcome as a composite of death, vegetative state, or severe disability (Lower only), corresponding to a score of 1 to 3 on the Extended Glasgow Outcome Scale, as indicated by the dot vertical line score of 1-3 as unfavourable.

References

- Hutchinson PJ, Kolias AG, Timofeev IS, et al. Trial of Decompressive Craniectomy for Traumatic Intracranial Hypertension. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2016; 375(12):1119-30. [pubmed]

- Cooper DJ, Rosenfeld JV, Murray L, et al. Decompressive craniectomy in diffuse traumatic brain injury. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2011; 364(16):1493-502. [pubmed]

- Nichol AD, Higgins AM, Gabbe BJ, Murray LJ, Cooper DJ, Cameron PA. Measuring functional and quality of life outcomes following major head injury: common scales and checklists. Injury. 2011; 42(3):281-7. [pubmed]

- Cooper DJ, Nichol A, Hodgson C. Craniectomy for Traumatic Intracranial Hypertension. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2016; 375(24):2402. [pubmed]

Response

Dr Hutchinson, Dr Kolias, and Dr Menon – three of the authors of the RESCUEicp trial – respond to this post in a subsequent LITFL blogpost titled “Beholder” or patients and families?

Chris is an Intensivist and ECMO specialist at The Alfred ICU, where he is Deputy Director (Education). He is a Clinical Adjunct Associate Professor at Monash University, the Lead for the Clinician Educator Incubator programme, and a CICM First Part Examiner.

He is an internationally recognised Clinician Educator with a passion for helping clinicians learn and for improving the clinical performance of individuals and collectives. He was one of the founders of the FOAM movement (Free Open-Access Medical education) has been recognised for his contributions to education with awards from ANZICS, ANZAHPE, and ACEM.

His one great achievement is being the father of three amazing children.

On Bluesky, he is @precordialthump.bsky.social and on the site that Elon has screwed up, he is @precordialthump.

| INTENSIVE | RAGE | Resuscitology | SMACC

Not really sure that both are 27%. If we change the dichotomization point you obtain 32% favorable outcomes in the DC group and 28,5% of favorable outcome in the medical treatment group, in which you should at least have any decency to say that that 37% of the patients in the medical group underwent as well a DC.

Having that said, if whatever you said was true and there was a 27% equal favorable outcome in both groups or if the 32% and 28,5% are not statistically different (taking in account that 37% of the patients in the medical group received a DC), what you could only say is that in this dichotomization group there are no differences, you could NEVER say that DC is NOT EFFECTIVE.

It’s great that you will never do neurosurgery.

A Neurosurgeon.