Roast duck and juniper beer

aka Pulmonary Puzzler 003

Consider a 73 year-old female admitted with vomiting and subsequent chest pain.

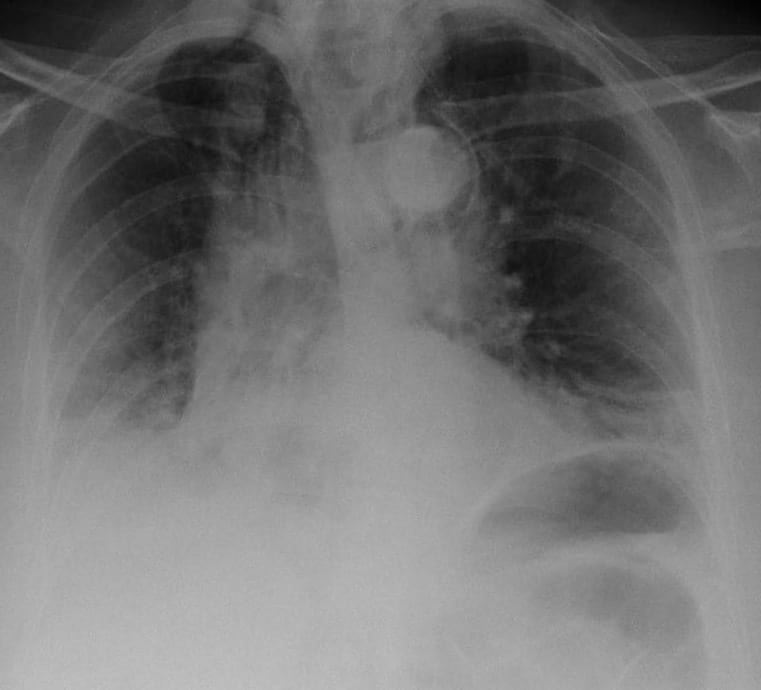

This is her erect AP admission chest X-ray.

Questions

Q1. Describe the chest X-ray?

Answer and interpretation

There is extensive mediastinal emphysema and bilateral pleural effusions.

Q2. What is the diagnosis?

Answer and interpretation

Boerhaave syndrome or so-called ‘spontaneous’ rupture of the oesophagus.

Often it is not really spontaneous as it occurs with vomiting.

Herman Boerhaave (1668-1738) described the condition in 1724, in a classic example of clinicopathological correlation, when faced with the case of the Grand Admiral of the Dutch Fleet, a roast duck and three litres of juniper beer…

Legend has it that letters Boerhaave received bore no address and were simply mailed “To the Greatest Physician in the World”.

– from Tan SY, Hu M. Hermann Boerhaave (1668-1738): 18th century teacher extraordinaire. Singapore Med J. 2004 Jan;45(1):3-5. PMID: 14976574

Q3. What is the classic presentation of this condition?

Answer and interpretation

“A middle-aged man presenting with sudden-onset severe chest or epigastric pain, often radiating to the back or shoulder, after repeated episodes of retching or vomiting in association with over-indulgence in food and alcohol.”

Most presentations of Boerhaave syndrome are atypical and the diagnosis often requires a high index of suspicion – usually an “oesophogram” of some sort is required.

In about 1 in 4 cases there is no history of vomiting!

Q4. What is the Mackler triad?

Answer and interpretation

The Mackler triad consists of:

- vomiting

- lower thoracic pain

- subcutaneous emphysema

Although it supposedly defines the classic features of Boerhaarve syndrome it is probably not worth knowing because it is rarely found and is of negligible clinical utility in the real world.

Q5. Outline the management of this condition.

Answer and interpretation

This a a highly lethal condition – it is essentially 100% fatal if left untreated. Overall mortality is about 30%.

The cornerstones of management are:

- aggressive resuscitation

- early surgical intervention

- broad-spectrum antibiotics

Resuscitation should be followed by prompt surgical intervention (call the thoracic surgeons!). The time between onset of symptoms and surgery is the greatest predictor of patient survival.

- best outcomes if surgery is performed <12 hours from onset.

- mortality probably increases to ~50% at 24 hours, and to ~90% at 48 hours.

Empirical antibiotics are indicated and should be broad spectrum to cover gram positives (including enterococcus), gram negatives and anaerobes. Some also advocate antifungal cover with fluconazole in initial empirical treatment as Candida is commonly grown from drain fluid in these patients (sometimes I give this and sometimes I don’t and I’m not sure whether doing this is a good idea or not).

Conservative management (i.e. without surgery) may be appropriate in some situations:

- presentation >48 hours

- debilitated premorbid condition

- a contained rupture, with minimal symptoms and negligible clinical evidence of sepsis.

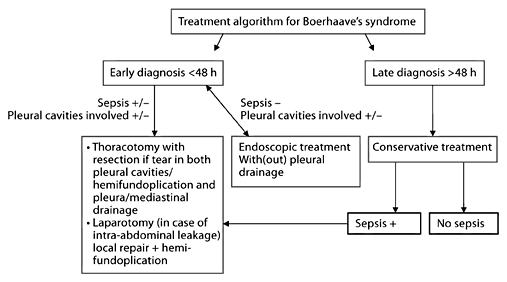

Although there is little consensus for the management of this rare condition, one suggested treatment algorithm is:

References

- For more Pulmonary cases check out the LITFL Top 150 Chest X-Rays

CLINICAL CASES

Pulmonary Puzzler

Intensivist in Wellington, New Zealand. Started out in ED, but now feels physically ill whenever he steps foot on the front line. Clinical researcher, kite-surfer | @DogICUma |