The True Angina

aka ENT Equivocation 003

A 44 year-old man presents to the ED 2 days after having an infected left mandibular second molar tooth extracted by his dentist. The patient has difficulty swallowing, neck pain, fevers and chills. He is a smoker, has poorly controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hyperlipidemia.

Bedside vitals: P 112/min, BP 115/75 mmHg, R 26/min, SpO2 93% OA, T 38.7°C, BSL 12.4mmol.

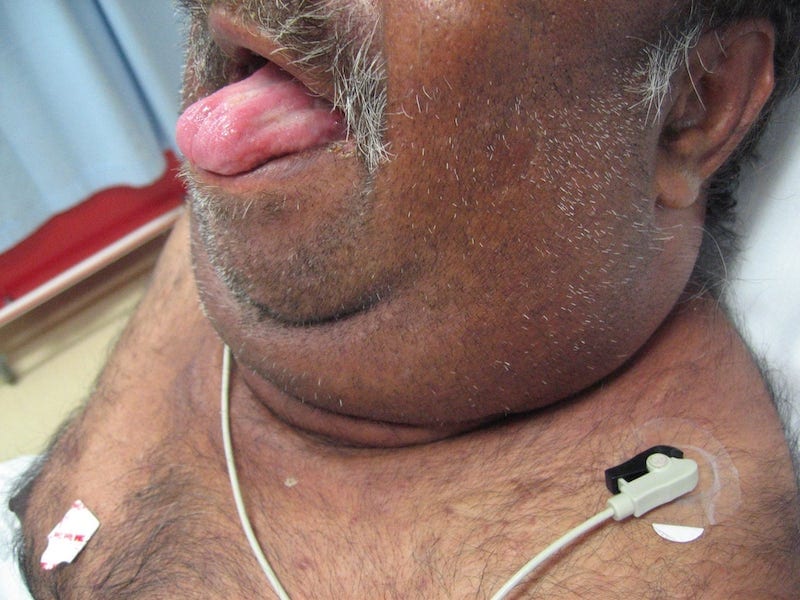

He is tender around his neck and throat but is able to swallow saliva, albeit with considerable pain. Oral examination reveals an elevated tongue with marked submandibular and sublingual swelling:

Questions

Q1. What is the likely diagnosis?

Answer and interpretation

This is a medical emergency that may progress to septic shock and threaten the airway…

Q2. Who first described this condition, and when?

Answer and interpretation

Wilhelm Frederick von Ludwig, described the condition in 1836 based on the observation of 5 patients with

…gangrenous indurations of the connective tissues of the neck that advanced to involve the tissues that cover the small muscles between the larynx and the floor of the mouth

Q3. Describe the pathophysiology of this condition.

Answer and interpretation

Ludwig’s angina, is a rapidly progressive cellulitis of the floor of the mouth, involves the submandibular, submaxillary, and sublingual spaces.

The infection typically occurs in those with poor dental hygiene or following dental procedures. The causative organisms are typical normal oral flora and infection is usually polymicrobial in nature.Causative organisms include:

- Streptococcus pyogenes

- Staphylococcus aureus

- Prevotella melaninogenicus

- Fusobacterium spp.

Ludwig’s angina usually occurs in patients with no comorbidities, but some groups may be at higher risk of developing the condition. This includes patients with:

- Diabetes mellitus

- Chronic alcohol abuse

- intravenous drug abuse

- HIV/ AIDS

- Malnutrition

- Poor oral hygiene

- and smokers

Q4. Describe the epidemiology of this condition

Answer and interpretation

Ludwig angina:

- mostly affects people between the ages of 20 and 60 years.

- has a male predominance.

- is uncommon in children, but can present with no obvious cause.

- Had mortality >50% before the advent of penicillin, and with today’s antibiotics, surgical interventions and high-level supportive care mortality is about 8%.

Q5. What are the clinical features of this condition?

Answer and interpretation

The clinical features of Ludwig’s angina can rapidly evolve.

Symptoms may include:

- Mouth and throat pain

- Fever and chills

- Difficulty in swallowing and drooling

- Trismus (limited mouth opening)

- Hot potato voice

- Stridor is a late-sign and signifies potentially life-threatening airway compromise

Signs may include:

- Fever, tachycardia, and progression to septic shock

- Bull neck appearance

- Tripod position and respiratory distress

- Tongue appears displaced superiorly and anteriorly, and inability to protrude the tongue

- Tenderness over the neck and throat

- Submandibular “woody” induration, crepitus or tenderness

Q6. What investigations would you consider?

Answer and interpretation

Ludwig’s angina is predominately a clinical diagnosis.Laboratory tests are of limited utility, but may include:

- FBC

- U&E

- LFT

- Lactate

- CRP

Imaging is performed to evaluate for:

- airway patency

- extent of soft-tissue swelling

- extension of infection

- presence of drainable abscesses and gas

- Underlying dental disease

CT is the imaging modality of choice. The timing and choice of imaging modality depends on the patient’s clinical stability, airway patency and their ability to lie flat — ensure the airway is secure first!

Findings on CT include:

- Local skin thickening

- Increased attenuation of subcutaneous fat

- Muscle enlargement

- Loss of fat planes within the submandibular space

- soft tissue emphysema and focal fluid collections

Q7. Describe your approach to managing this patient’s airway in the emergency department?

Answer and interpretation

Your priorities are to:

- Secure the airway early.

- Prepare and be ready for a difficult airway — expect that the patient will require a surgical airway.

- Prevent the development of septic shock and multi-organ failure — give antibiotics early.

Airway compromise due to expanding oedema of the soft tissues of the neck is the leading cause of death.

Assess for signs of impending or actual airway compromise:

- trismus with mouth opening limited to 2 cm or less(inter-incisal distance)

- inability ot flex the neck without airway obstruction

- Elevation or firmness of the tongue, or inability to protrude the tongue

- Dsyphagia

- Dyspnoea

- Stridor is a late sign

Approaching the airway:

- Assign roles and ensure that the most experienced airway doctor available is present — ask anesthetics and ENT to attend immediately.

- Have the difficult and surgical airway trolley at the bedside.

- Use the LEMON mnemonic to identify difficult laryngoscopy and intubation — patients with Ludwig’s angina should be considered difficult intubations by definition!

- Look externally — get an impression of potential airway difficulty based on obvious anatomical distortion.

- Evaluate airway geometry — (the 3-3-2 rule) measuring the geometry of the airway can predict the clinician’s ability to align the oral, pharyngeal, and tracheal axes.

- Mallampati score — assess the degree at which the tongue obstructs the visualisation of the posterior pharynx on mouth opening has some correlation with glottis view.

- Obstruction or Obesity — its important to recognise both as these may dictate airway management options.

- Neck mobility — neck immobility also interferes with the ability to align the visual axis by preventing the desired “sniffing position”.

Important considerations in securing the airway:

- You have some time, but not too much time — try to preoxgenate as much as possible before hand.

- Consider immediate transfer to the operating theater where a surgical airway can be optimally performed by an ENT specialist.

- Awake fiberoptic intubation should be considered in the clinically stable and cooperative patient — however for success you need a relatively clean airway free of blood and debris.

- Always have a surgical airway ready and as your back up plan.

- Blind insertion devices (e.g. intubating LMA) are not recommended as they are unlikely to be successful and may cause additional airway compromise during insertion attempts.

This is only a brief review of managing the difficult airway for more resources and an in-depth look check out:

- LITFL Own The Airway! — a collection of high quality free online videos covering everything from the basics to the most advanced aspects of emergency airway management.

- EMCrit: Failure to Plan for Failure: A Discussion of Airway Disasters — Scott interviews Jonathan Benger on the NAP4 study of airway complications in Great Britain.

- EmCrit: Needle vs. Knife: — Scott and Minh Le Cong discuss different approaches to the surgical airway.

Q8. What other management strategies are required in the ED?

Answer and interpretation

Specific management

Early administration of antibiotics:

- broad spectrum antibiotics within the first hour of recognition of infection/sepsis greatly reduces mortality.

Current Therapeutic Guidelines – Antibiotics recommended for Ludwig angina in Australia:

- Metronidazole 500mg IV every 12 hours AND Benzylpenicillin 1.2g IV every 6 hours

- For patients with non-immediate hypersensitivity to penicillin:

Cephazolin 1g IV every 8 hours. - For patients with immediate hypersensitivity to penicillin:

clindamycin 450 mg IV every 8 hours OR lincomycin 600 mg IV every 8 hours.

Steroids:

- Dexamethasone 8-12 mg IV initially then give in dose’s of 4-8mg every 6 hours for the first 48 hours.

- It’s postulated that dexamethasone provides initial chemical decompression by decreasing oedema and cellulitis, thus allowing improved penetration of antibiotics in the area.

Supportive care and monitoring

This patient requires 1:1 nursing care and monitoring:

- Patient will require continuous RR, ETCO2, ECG monitoring and invasive blood pressure monitoring.

- Fluid resuscitation to ensure adequate blood pressure and urine output.

- Indwelling catheter – ensure urine output of at lest 0.5-1mls/kg/hr.

- Stabilisation of blood sugar levels, and frequent monitoring.

- If airway secured consider lung protective ventilation strategies to prevent ARDS and ventilator associated pneumonia, including head up positioning.

- Consider other measures if patient boarded in ED for a while —- VTE and stress ulcer prophylaxis, regular pressure area care.

Remember FAST HUGS IN BED Please!

Disposition

- Early notification of ENT, anaesthetics and the operating theatres to facilitate definitive airway management.

- Early referral to the maxillofacial surgical team for surgical decompression of the sublingual, submental and submandibular spaces.

- Arrange for the patient to be admitted to ICU, for further supportive and post operative care.

So, what actually happened to this man?

Answer and interpretation

The patient had a rocky course — he was initially taken from ED to the operating theater where an emergency tracheostomy was performed by the ENT team.

He was then transferred to the CT scanner for imaging, and then back to the OT for surgical decompression of his submandibular and sublingual spaces. The patient arrived in ICU 8 hours after his initial presentation to the ED with two drain’s in-situ and ongoing discharge of purulent fluid.

Once weaned from the ventilator he spent another 6 days on the ward prior to being discharged home with a tracheostomyy in-situ, and a plan for its reversal in the near future.

References

- Buckley, M. & O’Connor, K. (2009). Ludwig’s angina in a 76-year-old man. Emergency Medicine Journal. 26(9), 679-680. PMID: 19700596

- Costain, N. & Marrie, T. (2011). Ludwig’s Angina. The American Journal of Medicine. 124, (2) 115-117. PMID: 20961522

- Duprey, K. & Rose, J. (2010). Ludwig’s Angina. The International Journal of Emergency Medicine. 3, 201-202. PMID: 21031047

- Ludwig, B. et.al. (2010). Diagnostic imaging in nontraumatic paediatric head and neck emergencies. RadioGraphics. 30, 781-799. PMID: 20462994, (full text).

- Ramadan, H. & Solh, A. (2004). An update on otolaryngology in critical care. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 169, 1273-1277. PMID: 15087296. (full text).

- Reynolds, S. & Chow, A. (2009). Severe soft tissue infections of the head and neck: A primer for the critical care physicians. Lung. 187, 271-279. PMID: 19653038

- Vissers, R. & Gibbs, M. (2010). The high-risk airway. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 28, 203-217. PMID: 19945607

- Wolfe, M. Davis, J. & Parks, S. (2011). Is surgical airway necessary for airway management in deep neck infections and Ludwig’s angina? Journal of Critical Care. 26, 11-14. PMID: 20537506

CLINICAL CASES

ENT equivocation