What do you do if a puma attacks?

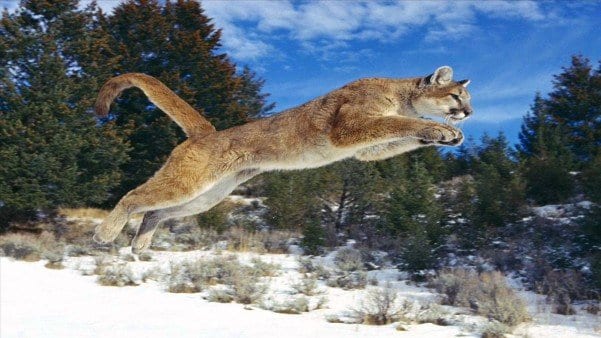

Pumas (Puma concolor) are large feline predators that have been known to attack humans. Slightly more concerning is that most attacks on humans are as prey, not as defense. Thus, there are often signs to warn people going into areas where pumas are common.

Doing a google image search will bring up comical parodies of said sign. But do the signs give good advice?

That was what the authors of this article set to find out. They looked at puma attacks in North America from 1890 to 2000, and found 185 attacks with injury, and 155 more close encounters with no injury. They then analysed the data to see if historically anecdotal risk factors for puma attacks were associated with higher likelihood of injury or death. The variables they analysed were:

- Age (<13 vs older)

- Group size (alone, two, or 3 or more)

- Movement (stationary, quickly, or slowly)

- Posture (crouching, upright, or on horseback/bicycle)

- Separation from group, and

- Noise making

As you can see, the sign above involves 5 of these classic variables. Age, separation from group, posture, noise-making, and movement. An argument can be made for saying that group size is inferred by the number of stick figures in the bottom left pictogram. Interestingly, a couple of those make little or no difference in an attack. There was no association with age or group size.

However, moving quickly did decrease likelihood of severe injury or death in proportion to no injury, while moving slowly or being stationary did not. Crouching versus upright posture did not differ in severity of attack, but being elevated (ie on horseback or bicycle) drastically reduced likelihood of injury or death. Being separated from a group has the highest relative risk, with no uninjured people. Not straying from your group gives you a 40% chance of being uninjured. Last, shouting does help a little over being quiet with regards to escaping uninjured. Doing something even louder (specifically in this article, shooting a gun) makes a larger difference, with a nearly 3:1 odds of escaping uninjured.

So what does this mean if you meet a puma in the wild? Mainly, you need to run away quickly(on a horse if possible). You should probably also carry an air horn, whistle, or some other loud noise-making device for an extra bit of safety. Also, stick with the rest of your party, as there is strength in numbers. Running away flies in the face of what the sign (and classic teaching) tells you, which is to slowly back away. Observations of predatory animals in the wild shows that they often stalk the slower moving members of the herd, as these are easy targets. The article even talks of observed predatory behavior captive cats have towards toddlers and those with unsteady gaits, so it makes sense not to appear weak or infirm to an animal trying to eat you.

And if and animal does attack you, fight back with every means possible.

Coss RG et al. The Effects of Human Age, Group Composition, and Behavior on the Likelihood of Being Injured by Attacking Pumas. Anthrozoös. 2009;22(1):77-87

Of note, while pumas carry multiple other names, such as mountain lion, catamount, and others, I specifically did not refer to the animal as a cougar, nor did I refer to the attacks as cougar attacks. I don’t need that kind of traffic coming from google searches.

Further Reading

- Hensley J. Big Cats and You. EBM Gone Wild

- Hensley J. How to survive a shark attack EBM Gone Wild

EBM Gone Wild

Wilderness Medicine

Emergency physician with interests in wilderness and prehospital medicine. Medical Director of the Texas State Aquarium, Padre Island National Seashore, Robstown EMS, and Code 3 ER | EBM gone Wild | @EBMGoneWild |

The only names we use for this large cat is ‘cougar’ or mountain lion. Why would you not use the name cougar?

The real reason?

Cougar has some innuendo involved with it.