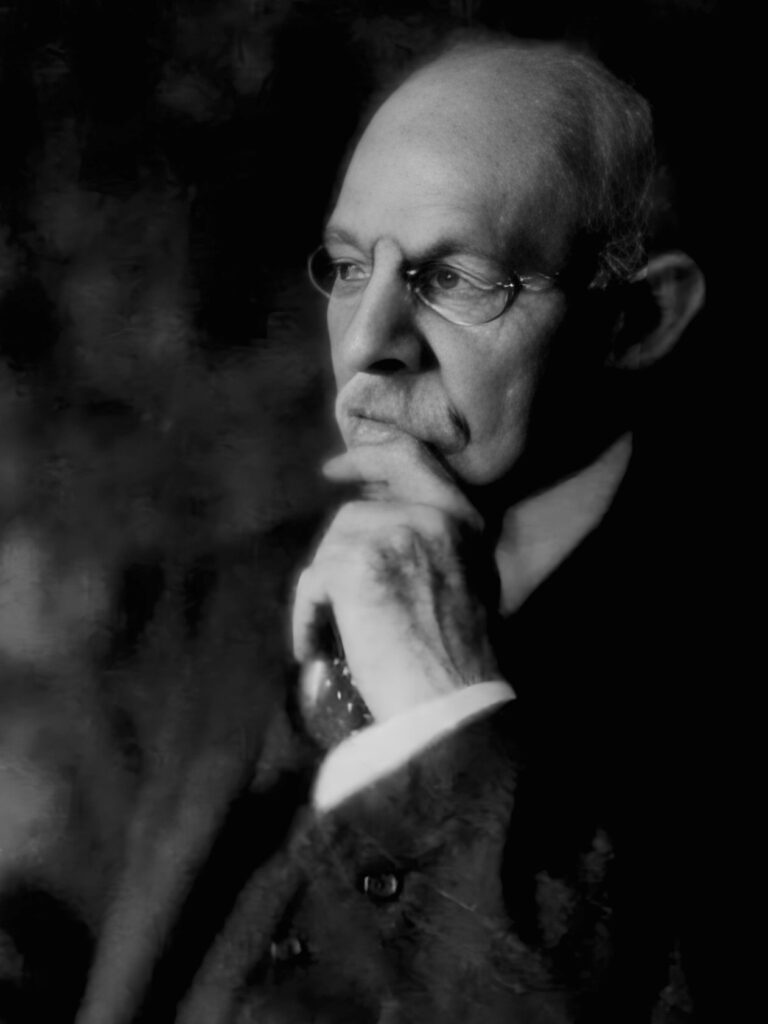

William Halsted

William Stewart Halsted (1852-1922) was an American surgeon and innovator; father of modern American surgery

Halsted was a pioneering American surgeon whose work reshaped surgical training, practice, and safety in the United States. One of the founding professors of Johns Hopkins Hospital and School of Medicine, he introduced surgical gloves, radical mastectomy for breast cancer, and the residency system. Despite personal struggles with drug addiction, Halsted’s scientific rigor and experimental discipline revolutionized surgical standards and patient outcomes.

Born September 23, 1852, in New York City, Halsted was raised in a prominent family and educated at Phillips Academy and Yale, where he was more renowned for athletics than academics. His interest in medicine crystallized during his senior year, prompting enrollment in the College of Physicians and Surgeons (Columbia). After graduating in 1877, he trained at Bellevue Hospital and studied advanced surgery and anatomy in Europe (1878–1880), absorbing cutting-edge techniques from luminaries like Billroth, Kaposi, and Zuckerkandl.

In New York, Halsted rose rapidly as a teacher, surgeon, and researcher, holding posts at several major hospitals. He led innovations in surgical charting, antisepsis, and nerve-block anaesthesia using cocaine—experiments which led to his own addiction. He underwent treatment at Butler Hospital and was recruited by William Welch to join Johns Hopkins, where he began rebuilding his career through research.

In 1890, Halsted became the first Chief of Surgery at Johns Hopkins Hospital and in 1892, its first Professor of Surgery. His approach emphasized meticulous technique, antisepsis, and scientific inquiry. He developed the Halstedian surgical residency model—a structured, progressive training system that became the standard globally. He also pioneered operations on the thyroid, hernia, and biliary tract, and famously introduced rubber gloves in the operating room.

Married in 1890 to Caroline Hampton (1861–1922), his surgical scrub nurse and niece of Confederate general Wade Hampton III, Halsted continued his work while leading a quiet, reclusive life in Baltimore. He died on September 7, 1922, of complications following surgery for gallstones.

Biography

- Born September 23, 1852 in New York City

- 1863–1869 – Attended Phillips Academy, Andover

- 1870–1874 – Undergraduate at Yale; captain of football team

- 1874–1877 – Studied at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons; graduated MD with distinction.

- 1876–1878 – Internship at Bellevue and New York Hospitals

- 1878–1880 – Postgraduate study in Vienna, Leipzig, Würzburg. Attended clinics under Chiari, Fuchs, Arlt, Politzer, Kaposi, Billroth, and Mikulicz

- 1880–1886 – Faculty at Columbia; attending surgeon at Bellevue, Roosevelt, Presbyterian Hospitals. Organized Mount Sinai outpatient ‘dispensary’ and remained its director until 1886

- 1881 – Performed a direct blood transfusion on his sister using his own blood to treat postpartum haemorrhage—one of the earliest recorded transfusions in the U.S.

- 1882 – Performed one of the first gallbladder operations in the U.S. on his mother, Mary Louisa Halsted, removing seven gallstones on her kitchen table

- 1884–1885 – Self-experimented with cocaine anaesthesia; developed cocaine addiction.

- 1886–1887 – Treated for addiction at Butler Hospital, Providence.

- 1886 – Joined William Welch’s research lab at Johns Hopkins

- 1889 – Named Chief of Surgery at Johns Hopkins Hospital.

- 1890 – Introduced rubber surgical gloves; married Caroline Hampton.

- 1892 – Appointed first Professor of Surgery at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

- 1904–1913 – Honored with multiple degrees and fellowships; became full-time faculty.

- Died September 7, 1922 in Baltimore, age 69.

Medical Eponyms

Halsted Gloves (1889–1890)

In 1889, William Stewart Halsted introduced rubber surgical gloves not as a sterile barrier, but to protect the hands of his scrub nurse and later wife, Caroline Hampton (1861–1922), from the harsh effects of mercuric antiseptics. He wrote:

In the winter of 1889 and 1890—I cannot recall the month—the nurse in charge of my operating-room complained that the solutions of mercuric chloride produced a dermatitis of her arms and hands. As she was an unusually efficient woman, I gave the matter my consideration and one day in New York requested the Goodyear Rubber Company to make as an experiment two pair of thin rubber gloves with gauntlets.

Their success led to wider adoption: initially worn by the assistant handling instruments (to guard against phenol), then by operators during joint surgery. Halsted recalled that it was likely his house surgeon, Dr. Joseph Bloodgood, who first wore gloves invariably and found them superior for surgical dexterity.

Rubber gloves were introduced by Professor Halsted soon after the hospital opened in 1889. They were invariably worn by the assistant who handed instruments and by the assistant at the wound, usually the nurse in charge of the operating-room. The operator [Halsted] himself rarely wore gloves (at that time) except when clean joints were opened.

The writer was the first as operator to wear gloves as a routine practice in practically all clean operations. He began to wear gloves invariably in December, 1896…Since wearing gloves he has operated in 100 cases of inguinal hernia and in only one case (recent) the wound suppurated

Bloodgood 1899 (Halsted’s assistant and House Surgeon)

Halsted later reflected that glove usage evolved gradually—more from practical benefit than a sudden insight—and acknowledged the early oversight in not recognising their full aseptic potential sooner.

Halsted Operation (Radical Mastectomy)

The Halsted operation, introduced in the 1890s, was the first standardized procedure for radical mastectomy in the treatment of breast cancer. It involved:

- Complete removal of the breast

- Excision of both pectoralis major and minor muscles

- Extensive axillary lymph node dissection

Halsted’s rationale was based on the belief that breast cancer spread contiguously through lymphatics and soft tissue. His method prioritized local control by removing all potentially affected structures in continuity. While later superseded by more conservative techniques, the Halsted operation remained the gold standard for over half a century.

Its legacy lies not only in improved cancer survival rates for the era but also in shaping oncologic surgical philosophy—emphasizing meticulous dissection, en bloc resection, and the principle of clear margins.

Halsted Syndrome

Halsted syndrome refers to chronic postoperative lymphedema of the upper limb following radical mastectomy, particularly after the Halsted operation. It results from:

- Extensive removal of axillary lymph nodes

- Disruption of lymphatic drainage

- Possible injury to the axillary vein or surrounding structures

Clinically, the syndrome manifests as persistent swelling, heaviness, and fibrosis of the affected arm. It became a recognized complication of Halsted’s aggressive surgical approach, especially in the pre-radiotherapy era.

The syndrome underscores the balance modern oncology must strike between oncologic control and functional preservation, and it contributed to the development of less radical and sentinel node-based approaches in breast cancer surgery.

Halsted Blood Transfusion (1881)

July 26, 1881– Halsted performed one of the earliest recorded human-to-human blood transfusions in the United States. While visiting his sister Minnie in Albany, New York, he found her critically ill from postpartum haemorrhage. With no time to spare, Halsted drew blood from his own arm using a syringe and injected it directly into hers. He later recounted:

After checking the hemorrhage, I transfused my sister with blood drawn into a syringe from one of my veins and injected immediately into one of hers. This was taking a great risk but she was so nearly moribund that I ventured it and with prompt results.

Remarkably, Minnie recovered. This procedure predated Karl Landsteiner’s 1901 discovery of blood types, which would later make transfusions safer. Halsted’s bold intervention underscored both the potential and perils of early transfusion practices

Halsted Cholecystectomy (1882)

1882 – Halsted performed one of the earliest documented gallbladder surgeries in the United States on his mother, Mary Louisa Halsted. The procedure took place on the kitchen table of his mothers home…

…Halsted was summoned in haste to his mother’s bedside at Albany and arrived in time to operate at 2am, he saved her life by draining an empyema of the gall-bladder which was about to rupture, and extracting seven gall-stones.

This operation highlights Halsted’s surgical skill; his willingness to apply emerging medical techniques in critical situations; and his innovative approach to surgery

Halsted’s Addiction and Its Impact

1884 – Halsted embraced cocaine as a promising new local anaesthetic, inspired by emerging reports from Europe. Alongside colleagues, he conducted self-experiments to test its efficacy—demonstrating the first regional nerve blocks and laying foundations for modern anaesthesia.

However, these experiments led to an unintended consequence: Halsted developed a cocaine addiction that disrupted his early career. Efforts to treat the dependency—then poorly understood—led to the substitution of morphine, resulting in a lifelong dual addiction.

Despite this, Halsted rebuilt his professional life at Johns Hopkins, where he became a founding figure in modern American surgery. He never resumed clinical cocaine use, and published little on anaesthesia, but was posthumously recognized in 1922 by the American National Dental Association for his pioneering role.

His story remains a compelling study in the risks of self-experimentation, the intersection of innovation and vulnerability, and the resilience that marked his surgical legacy

Halsted and nerve blocks

Halsted’s early work in nerve block anaesthesia not only transformed dental surgery but also laid the groundwork for the broader field of regional anaesthesia in medicine.

Halsted Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block (1884)

Halsted, alongside his colleague Dr. Richard Hall, pioneered the use of cocaine for regional nerve blockade, marking a significant advancement in dental anaesthesia. Their technique involved the direct injection of a 4% cocaine solution.

In 1884, Halsted performed one of the first successful inferior alveolar nerve blocks using cocaine as a local anaesthetic. His technique involved targeting the inferior dental (alveolar) nerve as it entered the mandibular canal. Dr. Richard J. Hall, who witnessed the event, reported:

Dr. Halsted gave Mr. Locke, a medical student, an injection of nine minims, trying to reach with the point of the needle the inferior dental nerve where it enters the dental canal. In from four to six minutes there was complete anaesthesia of the tongue, on the side where the injection had been given, extending to the median line and backward to the base as far as could be reached with a pointed instrument.

This method, known as the Halsted technique, became the foundational approach for mandibular anesthesia and remains widely taught and utilized in dental practices today. Despite its widespread adoption, the technique has a reported failure rate of 15–20%, prompting the development of alternative methods such as the Gow-Gates and Vazirani-Akinosi techniques, which offer higher success rates in certain clinical scenarios.

Halsted’s First Brachial Plexus Block (1885)

In 1885, William Halsted performed what is recognized as the first brachial plexus block at Roosevelt Hospital, New York. Using a surgical approach, he exposed the nerve roots of the brachial plexus in the neck and directly applied cocaine, a newly discovered local anaesthetic. The technique provided regional anaesthesia for upper limb procedures—a radical innovation at the time.

Halsted later recalled:

One of the major operations performed by me under cocaine anaesthesia during the winter of 1884–1885 was the freeing of the cords and nerves of the brachial plexus after injection of the roots of this plexus. This operation was performed in a large tent which I built on the grounds of Bellevue Hospital, having found it impossible to carry out antiseptic precautions in the general amphitheatre of Bellevue where the numerous anti-Lister surgeons dominated and predominated.

This pioneering effort laid the groundwork for modern regional anaesthesia and nerve block techniques, and marked one of the earliest applications of cocaine in clinical anaesthesia.

…and there is more

Halstedian principles

Halsted did not formally publish a consolidated list of surgical principles during his lifetime. Instead, what we now refer to as “Halsted’s Principles” or the “Tenets of Halsted” were derived posthumously from his meticulous surgical techniques and teachings. These principles were later articulated by his students and colleagues, notably Dr. Samuel James Crowe, who compiled them based on Halsted’s practices and observations

Crowe’s list of Halsted’s five surgical rules (from experience and notes, 1957)

- Wounds are resistant to infection when no bits of tissue have been crushed with clamps, torn by the rough handling of retractors, or devitalized by hastily and carelessly applied ligatures

- Wounds of parts rich in blood vessels usually heal without any visible granulation, even when no antiseptic precautions have been taken

- Incisions should be closed carefully and gently, layer by layer. The approximating sutures should never put the tissues under tension, since tension interferes with the blood supply. To avoid tension when closing wounds is one of the great principles of surgery

- The end of the forceps used to pick up bleeding points should be small, so as to avoid crushing and destroying the vitality of surrounding tissues

- A drain is essential when there is necrotic tissue and infection.

Modern Halstedian Principles (codified by surgical educators and historians)

- Gentle handling of tissue

- Meticulous haemostasis

- Preservation of blood supply

- Strict aseptic technique

- Minimum tension on tissues

- Accurate tissue apposition

- Obliteration of dead space

These principles have become foundational in surgical practice, emphasizing the importance of technique and patient safety. While Halsted may not have explicitly listed them, his legacy endures through these guiding tenets that continue to influence modern surgery

The Secret Operation on Rudolph Matas (1903)

In 1903, Halsted performed a clandestine operation on his colleague and fellow surgeon, Rudolph Matas (1860–1957), to remove a testicular mass. The nature and outcome of this procedure remained undisclosed during both men’s lifetimes.

Only upon Matas’s death in 1957 was it revealed during autopsy that he had undergone a right orchidectomy. This secretive episode underscores the deep personal and professional bonds among early surgical pioneers and reflects the era’s attitudes toward privacy and medical disclosure.

The Founding Four of Johns Hopkins Hospital

In 1889, Johns Hopkins Hospital opened with a revolutionary model that integrated patient care, research, and education. This transformation was led by four eminent physicians:

- William Henry Welch (1850–1934) – Pathologist; irst dean of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

- William Osler (1849–1919) – Internist and medical educator.

- Howard Atwood Kelly (1858–1943) – Gynaecologist and pioneer in surgical techniques.

- William Stewart Halsted (1852–1922) – Surgeon and innovator in surgical education.

Together, these “Founding Four” established a new paradigm in American medical training, emphasizing rigorous scientific research and structured clinical education .

Major Publications

- Halsted WS. Refusion in Carbonic-Oxide Poisoning, New York Med J 1883; 38: 625-629

- Halsted WS. Practical comments on the use and abuse of cocaine; suggested by invariably

- successful employment in more than a thousand minor surgical operations. NY Med J 1885; 42: 294–295.

- Halsted WS. Ligation of the First Portion of the Left Subclavian Artery and Excision of a Subclavio-Axillary Aneurism, Johns Hopkins Hosp Bull 1892; 3:93-94.

- Halsted WS. Auto- and Isotransplantation, in Dogs, of the Parathyroid Glandules, J Exp Med 1909; 11: 175-199.

- Halsted WS. The employment of fine silk in preference to catgut and the advantages of transfixing tissues and vessels in controlling haemorrhage; also an account of the introduction of gloves, guttapercha tissue and silver foil. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1913; 60(15): 1119–1126

- Halsted WS. Surgical papers. 1924 Volume I, Volume II

References

Biography

- William Stewart Halsted 1852-1922. Science. 1922 Oct 27;56(1452):461-4.

- Cushing H. William Stewart Halsted (1852-1922). Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 1923; 58(17): 599-604

- Matas R. William Stewart Halsted 1852-1922: an appreciation. Johns Hopkins Hospital Bulletin 1925; 36: 2-27.

- Heuer GW. Dr Halsted. Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital. 1952; 90(2)

- Crowe SJ. Halsted of John Hopkins; the man and his men. 1957

- William Stewart Halsted (1852-1922) surgeon of the “Hopkins Four”. JAMA. 1970 Sep 21;213(12):2072-4.

- Colp R Jr. Notes on Dr. William S. Halsted. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1984 Nov;60(9):876-87.

- Toledo-Pereyra LH. William Stewart Halsted: father of American modern surgery. J Invest Surg. 2002 Mar-Apr;15(2):59-60.

- Osborne MP. William Stewart Halsted: his life and contributions to surgery. Lancet Oncol. 2007 Mar;8(3):256-65.

- Abboud C. William Stewart Halsted (1852-1922). Embryo Project Encyclopedia 2017

- Fresquet JL. William Steward Halsted (1852-1922). Historia de la Medicina.

- Biography: Halsted, William Stewart (1852-1922). Plarr’s Lives of the Fellows Online. Royal College of Surgeons of England.

- Alan Wu. William Stewart Halsted – The Documentary

Addiction

- Brett WR. William Stewart Halsted (1852–1922) cocaine pioneer and addict. British Journal of Addiction. 1952; 49(1-2): 53-59

- Graner JL, Frederick W. William Halsted’s cocaine habit. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984 Dec;102(12):1746.

- Wright Jr. JR, Schachar, NS. Necessity is the mother of invention: William Stewart Halsted’s addiction and its influence on the development of residency training in North America. Can J Surg. 2020 Jan 16;63(1):E13-E19.

Eponymous terms

- Bloodgood JC. Operations on 459 cases of hernia in the Johns Hopkins hospital. The Johns Hopkins Hospital reports. 1899; VII(5): 223-374

- Day SB. Postscript to the surgical legend of William Stewart HALSTED and the introduction of rubber gloves to surgery. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1963 Jul;117:121-2.

- Olch PD. William S. Halsted and local anesthesia: contributions and complications. Anesthesiology. 1975 Apr;42(4):479-86.

- Classic articles in colonic and rectal surgery. William Stewart Halsted 1852-1922. Circular suture of the intestine–an experimental study. Dis Colon Rectum. 1984 Nov;27(11):755-7.

- Ellis H. Eponymns in oncology. William Stewart Halsted (1852-1922). Eur J Surg Oncol. 1985 Jun;11(2):203.

- Breathnach CS. The centenary of the surgical glove. J Ir Coll Physicians Surg. 1997 Oct;26(4):297-9.

- Alexander E Jr. The debt of neurosurgery to William Stewart Halsted (1852-1922). Surg Neurol. 1997 May;47(5):506-11.

- Germain MA. L’épopée des gants chirurgicaux [The advent of surgical gloves]. Ann Chir. 2003 Sep;128(7):475-80.

Eponym

the person behind the name

BA MA (Oxon) MBChB (Edin) FACEM FFSEM. Emergency physician, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital. Passion for rugby; medical history; medical education; and asynchronous learning #FOAMed evangelist. Co-founder and CTO of Life in the Fast lane | On Call: Principles and Protocol 4e| Eponyms | Books |