A Change in Condition

aka Postcards from the Edge 007a

2002 was the year I became a doctor. It is easy to forget the growing pains of the student-to-doctor metamorphosis. For me, the once vague notion of becoming a doctor was made real when I traveled to Zambia to work on the wards of St. Francis Hospital (SFH) in Katete:

Inevitably, every medical officer working at SFH encounters a tap on the shoulder from a nurse followed by the quiet echo of the whispered words, “Doctor, there has been a change in condition”.

Usually, this means a patient has died. Sometimes the patient is still in the last throes of trying to die. Invariably, there is very little that can be done. The patient may have been dead for sometime and an over-worked nurse has only just noticed his or her lack of responsiveness. Or you may find that the suction is not working or the mask and bag has gone missing, thus robbing the dying patient of a last breath. Woven together such experiences form the grim reality of life and death in a “developing” world hospital.

The phrase’a change in condition‘ also aptly described how my experiences in Zambia affected me. Many times I felt a chill and imagined myself a naïve Charlie Marlow journeying to the ‘Heart of Darkness’. At times the dying words of the maniacal Kurtz resonated in my thoughts – “he cried out twice, a cry that was no more than a breath – The horror! The horror!”. I too underwent a change in condition.

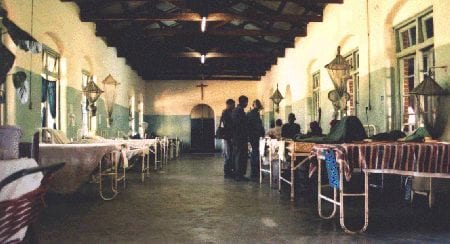

I remember my first ward round on a Sunday morning, two days after arriving in Lusaka. I was still jet-lagged but in a state of agitation fueled by curiosity and enthusiasm. The ward round covered all the surgical and obstetrical/ gynaecological patients in the hospital. This equated to approximately seventy or eighty patients (I couldn’t keep up with the fast pace of the count), and lasted barely two-and-a-half hours. My eyes could hardly adjust to the darkness of the wards, and when they did, they were barely prepared for what they saw. I was struggling to keep my head above water in an ocean of dripping pus, sunken eyes, and protruding ribs.

Soon after I arrived at SFH I paid a visit to the SCBU – the special care baby unit. The room was filled with stifling heat and the walls were lined with boxes with large windows. Through each window one could see a skeletal newborn staring back with eyes wide. A disturbing image of a department store filled with microwave ovens entered my mind; each containing assorted leftovers waiting to be re-heated. Actually I was fortunate – my arrival had followed the eradication of most of the cockroaches that once infested the SCBU. It was said, if one looked closely, that nibbled bite marks left by the cockroaches could still be seen on the tiny toes of the undernourished newborns.

Images are one thing, smells are another. My first walk through the SFH wards took me back to my childhood. As a youngster I used to hand-rear birds and kept an aviary. The background scent of the hospital had the same agricultural odour. As I circulated the hospital, many other scents – none pleasant – also came to the fore. These smells were representative of all the bodily functions of which human beings are capable, plus all the products of the fermentation of countless micro-organisms. Sometimes the odours were so strong I had to consider carefully whether a gasp of air was less harmful than death by asphyxiation.

My introduction to working on the male medical ward included admitting and treating a prisoner from the local jail. The man was in his early thirties. He was debilitated by a chest infection and chronic diarrhoea, which compounded his severe malnutrition and suppressed immune system. He had the appearance of a skeleton lightly clothed, in part, with a thin layer of dark skin. Pus gushed out of a wound an inch long upon lifting his right forearm, and the crackle of bacterial gas beneath the skin was palpable. The prisoner had sustained the injury by defending himself with a raised arm against the swing of a farmer’s hoe. The wound then shared the usual fate of a breach in the skin’s defence in Africa – infection. I helped the patient to lean forward, thus allowing his back to be examined. I was hit instantly by the surge of an insipid wave of ammonia that rose from his urine-soaked clothes. Across his back stretched a thick line of bleeding flesh, perhaps the only clean wound on his body (and probably an indication of the antiseptic quality of urine). His left ankle was a gaping purulent crater. Chronic osteomyelitis had eaten away at both his bony and soft tissues. Elsewhere, his body bore the numberless punctured impressions of human jaws. As time passed his leg wound teemed with hungry maggots that ate at the dead flesh, baring the ruptured tendons and decaying bones of his left foot. The surgeons eventually took over the man’s care. Last I heard, the poor man was accused of keeping himself sick to avoid a return to prison. Who could blame him?…

“The horror! The horror!”…

After my first day at SFH, I wondered how long it would be before I became desensitised to the enormity of my surroundings. Only a week later, it seemed almost normal to see a room of thirty young men, cachexic, with sunken eyes, and mouths filled with the white curd of candidiasis.

Initially, I felt that medicine in Zambia was a hopeless enterprise. However, I soon learnt to value the things that could be done. Treating candidiasis to allow a man to swallow with some comfort, or giving analgesia to relieve the bone pain of multiple myeloma are brief examples. While there seemed to be a strong palliative component to medicine on the wards, many conditions were curable. There are few occasions in life as rewarding as helping a fitting child to fight off cerebral malaria, bringing a young man back to consciousness with the treatment of life-threatening bacterial meningitis, or hearing a man offer his thanks after the spasms of tetanus have subsided.

At SFH I experienced the fullest range of human emotion. I experienced the greatest challenges of my short medical life. I had my eyes opened to a world I had never before seen. The time I spent at SFH was beyond value and will continue serve me well for the rest of my personal and professional life.

Nickson C, 2002

I went to Africa a student and came back a doctor.

LITFL Zambia related notes

- A Change in Condition

- The Shrinking Feet of the Man from Malawi

- A Midsummer Night’s Dream

- World AIDS Day and the Crisis in Zambia

POSTCARDS

from the edge

Chris is an Intensivist and ECMO specialist at The Alfred ICU, where he is Deputy Director (Education). He is a Clinical Adjunct Associate Professor at Monash University, the Lead for the Clinician Educator Incubator programme, and a CICM First Part Examiner.

He is an internationally recognised Clinician Educator with a passion for helping clinicians learn and for improving the clinical performance of individuals and collectives. He was one of the founders of the FOAM movement (Free Open-Access Medical education) has been recognised for his contributions to education with awards from ANZICS, ANZAHPE, and ACEM.

His one great achievement is being the father of three amazing children.

On Bluesky, he is @precordialthump.bsky.social and on the site that Elon has screwed up, he is @precordialthump.

| INTENSIVE | RAGE | Resuscitology | SMACC