Bell’s Palsy

Bell’s palsy is one of the most common neurologic disorders affecting the cranial nerves. It is an abrupt, isolated, unilateral, peripheral facial paralysis without detectable cause.

Bell’s palsy is the most common cause of facial paralysis worldwide.

History

The Scottish anatomist, physiologist, neurologist, surgeon and artist, Sir Charles Bell (1774–1842), first described the anatomy and function of the facial nerve in the early 1800s.

Bell’s initial description in 1821 involved facial paralysis caused by trauma to peripheral branches of the facial nerve. His description of idiopathic facial nerve paralysis appeared in Appendix to the papers on the nerves in 1827.

The first modern published description of a lower motor neuron (LMN) seventh cranial nerve palsy appears to have been in 1798 by German physician Nicolaus Anton Friedreich (1761-1836)

Anatomy

The facial nerve (seventh cranial nerve) has two components:

- Motor fibres innervating muscles of facial expression.

- Visceral mixed root:

- Parasympathetic fibres to lacrimal, submandibular, and sublingual glands.

- Afferent fibres for taste from the anterior two-thirds of the tongue.

- Somatic afferents from the external auditory canal and pinna.

Pathophysiology

Bell’s palsy is defined as idiopathic facial paralysis.

Proposed Causative Mechanisms

- Viral infection:

- Herpes simplex virus.

- Herpes zoster.

- Microvascular lesions (e.g. in diabetics).

- Inflammatory (likely autoimmune).

- There have been associations with an immune-mediated response to some vaccines (e.g. an intranasal influenza vaccine used in 2000 and SARS-CoV-2 vaccines).

- However, the causal role of vaccines remains uncertain and controversial, as the case rate may simply reflect background incidence.

Complications

Potential complications include:

- Corneal drying → ulceration and infection.

- Loss of taste over anterior two-thirds of the tongue.

- Hyperacusis (due to nerve to stapedius involvement).

- Drooling, difficulty with eating and speech.

- Incomplete recovery.

- Aberrant regeneration:

- Co-contraction of facial muscles (synkinesis).

- Involuntary tearing when eating (crocodile tears).

- Gustatory sweating.

- Depression, which may be profound.

Clinical Features

Bell’s palsy is a clinical diagnosis of exclusion.

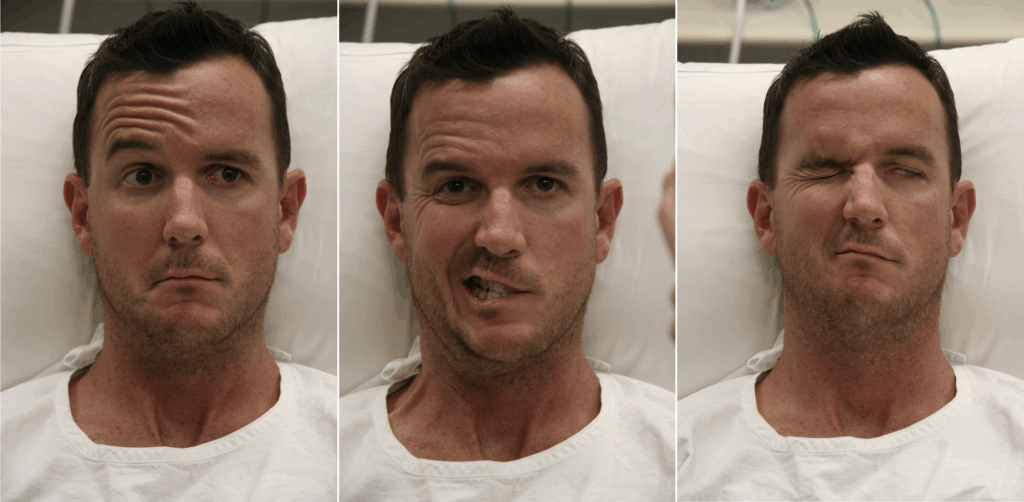

Main Clinical Features

- Pain behind the ear over the mastoid — often precedes facial paralysis.

- Possible history of recent viral illness.

- Lower motor neuron seventh cranial nerve lesion:

- Weakness/paralysis of upper and lower facial musculature on the affected side.

- Forehead sparing suggests a central (upper motor neuron) lesion.

- Onset is rapid (hours to 1–2 days).

Associated Symptoms

- Drooling.

- Altered taste.

- Tearing.

- Altered hearing.

- Difficulty closing the eye (Bell’s sign — eye rolls upward).

- Subjective feeling of numbness (without true sensory loss).

- Hyperacusis may occur; deafness is not typical.

- Other cranial nerves: normal.

- Tympanic membranes: should not be inflamed.

- Vesicles → consider Ramsay Hunt syndrome.

- Depression is common.

- Search carefully for vesicular lesions (ear, throat, face) suggestive of Ramsay Hunt syndrome.

Natural History

- Course varies: early complete recovery → substantial nerve injury with sequelae.

- Most patients develop incomplete paralysis and recover fully.

- Poorer prognosis in:

- Complete paralysis.

- Loss of taste on anterior two-thirds of the tongue.

- Maximal weakness reached within 3 weeks; some recovery should be seen by 6 months.

- If no facial function returns by 4 months, alternative aetiologies should be considered.

- Recurrence occurs in 7–15% of cases.

Differential Diagnoses

Consider other causes of LMN seventh cranial nerve lesions:

- Ramsay Hunt syndrome.

- Middle ear pathology / mastoiditis.

- Trauma.

- Parotid gland pathology.

- Previous surgery.

- Tick envenomation.

Investigations

Bell’s palsy remains a clinical diagnosis. Investigations are used to exclude other pathology.

Blood Tests

- FBE & blood film:

- Rarely, LMN seventh nerve palsy can be the first presentation of haematological malignancy (especially in children).

- In known leukaemia, new LMN seventh nerve palsy warrants thorough evaluation for CNS relapse.

CT Scan

- Not routinely indicated unless the diagnosis is unclear or atypical features are present.

- High-resolution contrast-enhanced CT may be used when MRI is unavailable.

MRI

- Investigation of choice.

- Enhancement not seen in all cases (reported 57–100%).

- Normal enhancement pattern: geniculate ganglion and mastoid segments.

- In Bell’s palsy:

- Long segments enhance uniformly.

- A prominent fundal tuft sign may be seen.

- Nodularity suggests a possible neoplastic cause → search for leptomeningeal enhancement.

Electrophysiologic Studies

- Rarely performed emergently.

- EMG may assess the degree of nerve injury — more for prognosis, not acute workup.

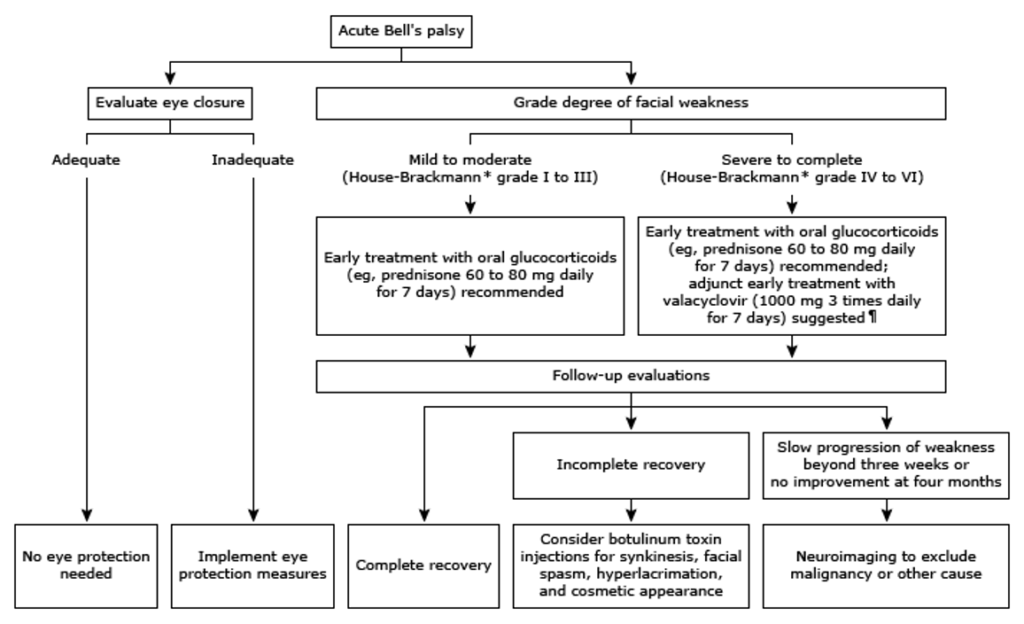

Management

1. Steroids

- Early oral corticosteroids (within 72 hours) significantly improve recovery.¹

- Prednisolone: 1 mg/kg (up to 75 mg) orally daily for 5 days.²

2. Eye Care

Essential when the patient cannot fully close the eye.

- Glasses or protective pad during the day.

- Micropore tape / eye pad at night.

- Lubricating eye drops (artificial tears) during the day:

- Poly-Tears — 1 drop every 1–12 hrs.

- Ointment at night:

- Poly-Visc.

- Consider ophthalmology referral if the eye cannot fully close (consider lateral tarsorrhaphy).

3. Antiviral Agents

- Viral aetiology is suspected; evidence for routine antivirals is low.

- Antivirals may be considered in severe cases (complete paralysis).

- Some clinicians use antivirals even in milder cases based on Pascal’s Wager principle.

- If Ramsay Hunt syndrome is suspected → definitely give antivirals.

- Options: acyclovir, valacyclovir, famciclovir.

- Severity can be guided using the House-Brackmann classification.

4. Psychiatric Support

- Support/counselling may be required due to psychological impact.

Disposition

- Close follow-up is required.

- GP review is usually sufficient.

- Refer to neurology if:

- Severe or atypical cases.

- No improvement at 4 months.

- Ophthalmology referral if the eye cannot close.

House-Brackmann Classification of Facial Nerve Dysfunction

| Grade | Severity | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Normal | Normal in all areas |

| 2 | Mild dysfunction | Gross: Slight weakness noticeable on close inspection; May have slight synkinesis; Normal symmetry and tone at rest Motion: Forehead (moderate to good function); Eye (complete closure with minimal effort); Mouth (slight asymmetry) |

| 3 | Moderate dysfunction | Gross: Obvious but not disfiguring difference between the two sides; Noticeable but not severe synkinesis, contracture, or hemifacial spasm; Normal symmetry and tone at rest. Motion: Forehead (slight to moderate movement); Eye (complete closure with effort); Mouth (slightly weak with maximum effort) |

| 4 | Moderately severe dysfunction | Gross: Obvious weakness and/or disfiguring asymmetry; Normal symmetry and tone at rest Motion: Forehead (none); Eye (incomplete closure); Mouth (asymmetric with maximum effort) |

| 5 | Severe dysfunction | Gross: Only barely perceptible motion; Asymmetry at rest Motion: Forehead (none); Eye (incomplete closure); Mouth (slight movement) |

| 6 | Total paralysis | No movement |

References

Publications

- Sullivan FM, Swan IR, Donnan PT, Morrison JM, Smith BH, McKinstry B, Davenport RJ, Vale LD, Clarkson JE, Hammersley V, Hayavi S, McAteer A, Stewart K, Daly F. Early treatment with prednisolone or acyclovir in Bell’s palsy. N Engl J Med. 2007 Oct 18;357(16):1598-607.

- Chiang LY, Crawford JR, Kuo DJ. Unilateral facial nerve palsy as an early presenting symptom of relapse in a paediatric patient with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. BMJ Case Rep. 2017

- Gagyor I, Madhok VB, Daly F, Somasundara D, Sullivan M, Gammie F, Sullivan F. Antiviral treatment for Bell’s palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Nov 9;(11):CD001869

- Sullivan F, Daly F, Gagyor I. Antiviral Agents Added to Corticosteroids for Early Treatment of Adults With Acute Idiopathic Facial Nerve Paralysis (Bell Palsy). JAMA. 2016 Aug 23-30;316(8):874-5.

FOAMed

- Sanger G. Bell’s Palsy. LITFL

- Sanger G. Sir Charles Bell. LITFL

Fellowship Notes

MBBS DDU (Emergency) CCPU. Adult/Paediatric Emergency Medicine Advanced Trainee in Melbourne, Australia. Special interests in diagnostic and procedural ultrasound, medical education, and ECG interpretation. Co-creator of the LITFL ECG Library. Twitter: @rob_buttner

Educator, magister, munus exemplar, dicata in agro subitis medicina et discrimine cura | FFS |