Blind, Aching and Vomiting

aka Ophthalmology Befuddler 007

A middle-aged woman presents to the emergency department complaining of decreased vision and an aching pain in her right eye. She says it came on after an argument with her husband earlier in the evening. The eye pain has progressed to a frontal headache. She could hardly read anything on a Snellen’s chart, and while you were assessing her visual acuity she started to vomit.

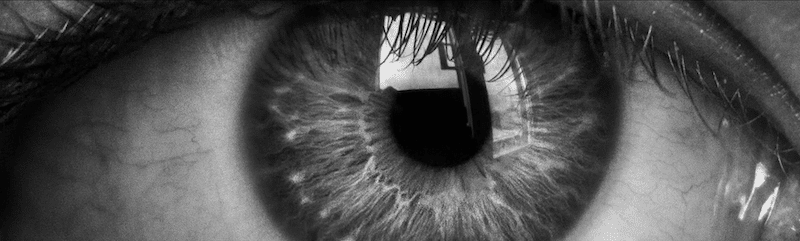

This is what her right eye looks like:

Questions

Q1. What is the likely diagnosis?

Answer and interpretation

Acute closed-angle glaucoma

This is new onset raised intraocular pressure resulting from failure of the trabecular drainage system. It causes loss of vision by compression of the optic disc.

Aqueous humour is produced by the ciliary bodies in the posterior segment. It circulates forwards into the anterior chamber (AC). It is resorbed through the trabecularmeshwork into the canal of Schlemm which drains into episcleralveins. The aqueous humour provides structural integrity to the eye,provides oxygen and nutrients to avascular structures like the lens and the cornea, and disperses waste products.

Q2. What are the possible underlying causes of this condition?

Answer and interpretation

Acute angle closure glaucoma can be primary or secondary.

Primary causes

- Pupillary block — this occurs when the posterior iris contacts the lens, blocking the flow of aqueous humour from the posterior chamber to the anterior chamber. The resulting increase in posterior chamber pressure pushes the iris forward and blocks the trabecular meshwork.

- Angle crowding — this may occur due to an abnormally configured iris, e.g. plateau iris, that obstructs the angle during pupillary dilatation.

Secondary causes (numerous)

- peripheral anterior synechiae (PAS) pulling the angle closed, e.g. uveitis (may become chronic)

- neovascular glaucoma, e.g. diabetes mellitus

- membranous obstruction, e.g. iridocorneal endothelial syndrome

- lens-induced, e.g. large lens or small eye

- drugs, e.g. topiramate and sulfonamides can cause ciliary body swelling

- choroidal swelling, e.g. central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) or post-op/ laser treatment

- posterior segment tumour

- hemorrhagic choroidal detachment

- aqueous misdirection syndrome

Q3. What are the risk factors for the primary form of this condition?

Answer and interpretation

Risk factors for pupillary block include:

- shallow anterior chamber

- female

- age

- Asian ethnicity

- long sightedness (hyperopia)

- family history

Q4. What are the possible precipitating factors in the primary form of this condition?

Answer and interpretation

The acute event may be precipitated by:

- topical mydriatics

- anticholinergic and sympathomimetic drugs

- emotional stimuli

- accommodation (e.g. reading)

- dim light

Q5. What features on history and examination should be looked for?

Answer and interpretation

History:

- frontal headache, nausea and vomiting

- eye pain, blurred vision, coloured halos around lights

- risk factors?

- precipitants?

Examination:

- Visual acuity (VA) — decreased

- Pupil — fixed irregular semidilated (midposition)

- Slit lamp — shallow AC (closed angle), injected conjunctiva; corneal microcystic edema. Consider secondary causes, e.g. synechiae, neovascularisation.

- Tonometry — high intraocular pressure (IOP). The eye is tense and tender on palpation. Note that angle-closure glaucoma can occur in the absence of high IOP.

- Fundoscopy — pronounced cupping or spontaneous arterial pulsations signifies the need for urgent treatment. Rule out CRVO and hemorrhage.

The angle is also narrow or occluded in the patients other eye in primary acute closed-angle glaucoma

If the patient presents very early in the attack, there may be very few examination findings.

Q6. What is the management?

Answer and interpretation

Urgent ophthalmology referral — severe and permanent damage may occur within hours.

Urgent treatment is needed if:

- Visual acuity is HM (hand movements only) or worse

- there is pronounced cupping

- spontaneous arterial pulsations are observed on fundoscopy

If IOP <50 mmHg and there is little visual impairment topical therapy is usually sufficient. The mainstays of urgent management are:

- head up — at least 30 degrees

- topical b-blocker — e.g. timolol 0.5% 1-2 drops as a single dose (caution if bronchospasm or heart failure)

- topical cholinergic (miotic) — e.g pilocarpine 2 or 4 % eyedrops — one-two drops q15min until pupillary constriction occurs (a 2% solution may be better in blue-eyed patients and a 4% solution in brown-eyed patients); especially if angle crowding is suspected.

- topical alpha2-agonist — e.g., apraclonidine 1% 1-2 drops as a single dose.

- carbonic anhydrase inhibitor — e.g. acetazolamide 500mg IV, or PO if IV not available (not if topiramate or sulfonamide-induced acute closed angle glaucoma)

Additional treatments:

- symptomatic treatment of pain and nausea/ vomiting

- if IOP and visual acuity have not improved in 1 hour, consider mannitol (e.g. 1-2 g/kg IV over 45 minutes)

- discontinue any precipitants and treat underlying causes

The ophthalmologist may also opt for one or more these therapies:

- topical steroid — e.g., prednisolone acetate 1%

(topical steroids should only be administered by an ophthalmologist) - compression gonioscopy — determines if trabecular blockage is reversible and may break the acute attack

- peripheral iridotomy may be required

(often performed in the asymptomatic eye as well as a preventative measure) - Specific secondary causes may require specific therapies and laser surgery may be required for in some cases (e.g. argon laser gonioplasty)

Q7. How is open angle glaucoma different from this condition?

Answer and interpretation

Open angle glaucoma is a leading cause of blindness in the developed world. It is a chronic condition, usually affecting both eyes and typically occurs in the elderly.

It is characterised by:

- reduced visual acuity

- relatively late onset visual field losses

- raised intra-ocular pressures

- progressive cupping of the optic disc.

Treatment is with topical agents (similar to those used for acute closed angle glaucoma) and surgery.

Q8. What is a normal intraocular pressure?

Answer and interpretation

10-20 mmHg

Patients with intraocular pressures higher than this should be followed up by an ophthalmologist.

Q9. Why is visual acuity more important in the assessment of this condition than tonometry?

Answer and interpretation

Glaucoma is really best viewed as a type of optic neuropathy. Patients vary in their susceptibility to intra-ocular pressure changes. Glaucoma can occur at ‘normal’ intraocular pressures, and other patients appear unaffected by chronic intraocular hypertension.

Q10. What is shown above?

Answer and interpretation

A pale, cupped optic disc — the hallmark of chronic glaucoma.

Q11. What is cupping?

Answer and interpretation

A sustained rise in intraocular pressure causes ‘atrophy’ of optic nerve fibers. This occurs centrally causing an enlargement of the central cup of the optic nerve. The normal cup-to-disk ratio is 0.3.

A cup-to-disk ratio >0.6 is characteristic of chronic glaucoma.

References

- Ehlers JP, Shah CP, Fenton GL, Hoskins EN. The Wills Eye Manual: Office and Emergency Room Diagnosis and Treatment of Eye Disease Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

- NSW Statewide Opthalmology Service. Eye Emergency Manual — An illustrated Guide. [Free PDF]

OPHTHALMOLOGY BEFUDDLER

Chris is an Intensivist and ECMO specialist at The Alfred ICU, where he is Deputy Director (Education). He is a Clinical Adjunct Associate Professor at Monash University, the Lead for the Clinician Educator Incubator programme, and a CICM First Part Examiner.

He is an internationally recognised Clinician Educator with a passion for helping clinicians learn and for improving the clinical performance of individuals and collectives. He was one of the founders of the FOAM movement (Free Open-Access Medical education) has been recognised for his contributions to education with awards from ANZICS, ANZAHPE, and ACEM.

His one great achievement is being the father of three amazing children.

On Bluesky, he is @precordialthump.bsky.social and on the site that Elon has screwed up, he is @precordialthump.

| INTENSIVE | RAGE | Resuscitology | SMACC