Blown out

aka Ophthalmology Befuddler 014

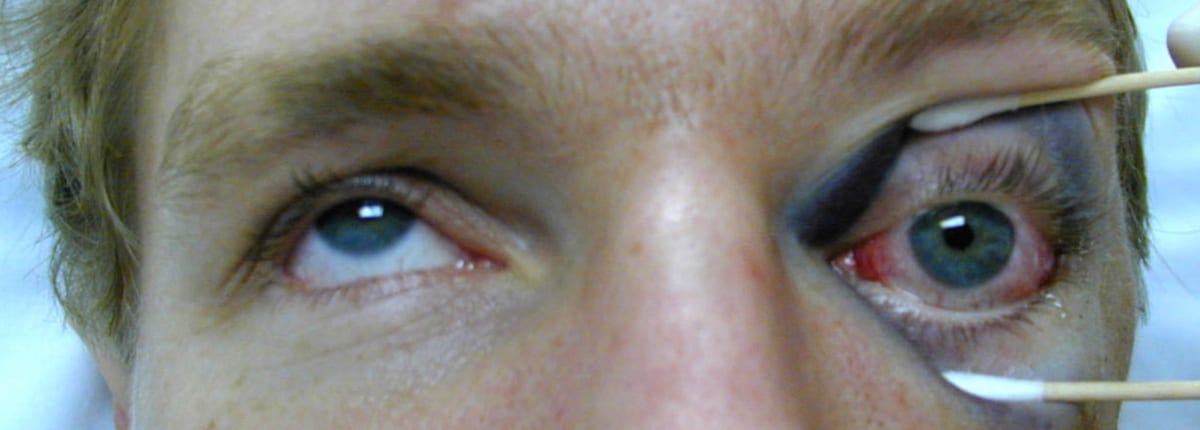

A 26 year-old man presents with left periorbital swelling and double vision after being hit in the eye by a high-speed squash ball.

Facial radiographs were obtained and the Waters view (occipitomental view) is shown:

Questions

Q1. What is the diagnosis?

Answer and interpretation

Blowout fracture

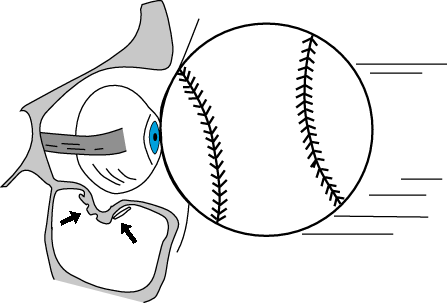

An injury resulting in an increase in intra-orbital pressure has ‘blown out’ the floor of the left orbit with the displacement of fragments into the maxillary sinus.

There are at least two theories explaining this mechanism:

- the ‘hydraulic theory‘ — the force of the impact is transmitted from the globe to the orbit, which fractures at its weakest point: the floor.

- the ‘buckling theory‘ — the orbital floor buckles and fractures due to a direct blow to the orbital rim.

Q2. What are the radiographic features of this injury?

Answer and interpretation

On the Waters view:

- The depressed fragment appears as an oblique line or ‘trapdoor‘ near the roof of the maxillary sinus.

- prolapsed soft tissue classically gives rise to the ‘tear drop‘ sign.

- Maxillary sinus opacification is seen with an air-fluid level.

- Inferior orbital rim and lateral wall of the maxillary sinus should be intact.

- Sometimes orbital emphysema is the only radiographic evidence that can be seen.

- Overlying soft tissue is a nonspecific finding.

Q3. What features on history and examination should be assessed for?

Answer and interpretation

History:

- mechanism of injury — typically blowout fractures result from an injury that increases the intraorbital pressure such as a blow from a fist or a small ball striking the eye/orbit at high speed.

- symptoms — pain (especially on vertical movement), local tenderness, diplopia (especially on vertical gaze), eyelid swelling and crepitus after nose blowing

Examination:

- epistaxis, ptosis, localised tenderness

- restricted eye movements, particular on vertical gaze, resulting in diplopia

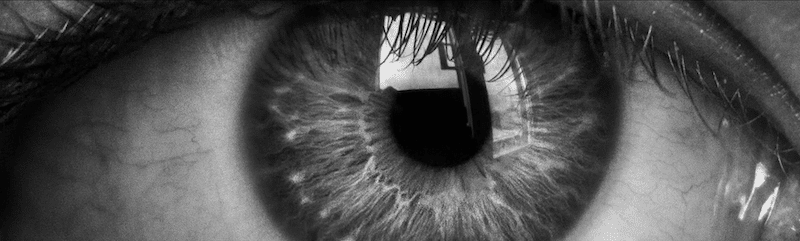

- complete eye examination looking for evidence of ocular injury, e.g. hyphema, subconjunctival hemorrhage, retro-orbital hemorrhage, retinal detachment and vitreous hemorrhage.

- check for infraorbital nerve involvement — anesthesia of the affected cheek, and the upper teeth and gums on the affected side. this nerve passes along the floor of the orbit and be stretched or otherwise damaged.

- palpate the eyelid for crepitus

- there may be no other significant facial injury.

Q4. Describe the investigation and management of a blowout fracture?

Answer and interpretation

A CT scan of the orbits and brain may be required depending on the mechanism and associated injuries. However, the Caldwell (occipitofrontal) and Waters (occipitomental) facial radiographic views are often sufficient.

Early treatment includes:

- nasal decongestants for 1 week

- prophylactic antibiotics, e.g. cephalexin 500mg qid po

- instruct the patient to avoid nose blowing and valsalva maneuvers; and to avoid driving until diplopia resolves.

- apply an ice pack to the orbit for 1-2 days

Q5. What is the appropriate disposition and follow up?

Answer and interpretation

- Ophthalmology referral is required for suspected orbital floor fractures (Maxillofacial surgeons manage these cases in some centres).

- Follow up in 1 week post-trauma to check for persistent diplopia or enophthalmos. Entrapment may resolve with the resolution of edema.

- Surgical repair is usually performed 1-2 weeks after the injury if required

Q6. What injuries need to be considered if the patient has relative afferent pupillary defect in the left eye?

Answer and interpretation

This suggests the presence of traumatic optic neuropathy, vitreous hemorrhage, retinal detachment or intracranial injury (e.g. asymmetric damage to the optic chiasm).

Traumatic optic neuropathy may result from:

- compressive optic neuropathy — retrobulbar hemorrhage, orbital foreign body or orbital emphysema

- optic nerve sheath hematoma

- optic nerve head avulsion

- optic nerve laceration

and result from either direct or indirect mechanisms:

- direct — e.g. apical orbital fracture

- indirect — e.g. deceleration injury (e.g. head versus steering wheel) resulting in shearing of pial vessels to the optic nerve

Emergent ophthalmologist consultation is warranted.

Q7. What other types of orbital fractures are there?

Answer and interpretation

Orbital fractures may be classified as:

- affecting the orbital rim

- affecting the orbital walls

- part of more complex midface fractures

Those affecting the orbital walls include:

- apical fractures — usually involve severe and potentially lethal forces, and associated with involvement of the optic canal and traumatic optic neuropathy.

- superior wall fractures — herniatiation into the frontal sinus is rare but there may be extension to the posterior wall of the frontal sinus and a CSF leak.

- medial wall fractures — associated with more extensive midface and nasal injuries. There may be soft tissue herniation into the ethmoid sinuses through the lamina papyracea (medial wall). Diplopia and exophthalmos are characteristic.

- fractures involving multiple walls of the orbit — associated with extensive midface fractures. There is no universally accepted classification system

Transverse section of CT Face showing a right medial orbital wall fracture. Although the lamina papyracea is the thinnest part of the orbital wall, it is not the weakest part as it is buttressed by the ethmoid air cells.

References

- Ehlers JP, Shah CP, Fenton GL, Hoskins EN. The Wills Eye Manual: Office and Emergency Room Diagnosis and Treatment of Eye Disease Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

- NSW Statewide Opthalmology Service. Eye Emergency Manual — An illustrated Guide. [Free PDF]

OPHTHALMOLOGY BEFUDDLER

Chris is an Intensivist and ECMO specialist at The Alfred ICU, where he is Deputy Director (Education). He is a Clinical Adjunct Associate Professor at Monash University, the Lead for the Clinician Educator Incubator programme, and a CICM First Part Examiner.

He is an internationally recognised Clinician Educator with a passion for helping clinicians learn and for improving the clinical performance of individuals and collectives. He was one of the founders of the FOAM movement (Free Open-Access Medical education) has been recognised for his contributions to education with awards from ANZICS, ANZAHPE, and ACEM.

His one great achievement is being the father of three amazing children.

On Bluesky, he is @precordialthump.bsky.social and on the site that Elon has screwed up, he is @precordialthump.

| INTENSIVE | RAGE | Resuscitology | SMACC