Fever, Rash and a Vuvuzela

aka Tropical and Travel Troubles 001

A 34 year-old man became unwell soon after arriving in Australia, having recently traveled to South Africa to watch the soccer World Cup. He hasn’t even felt like using the vuvuzela he bought.Unwell for 4 days, his symptoms include malaise, poor appetite, cough, and fever. He has bilateral conjunctivitis and an erythematous macular rash has started to appear on his neck and face.

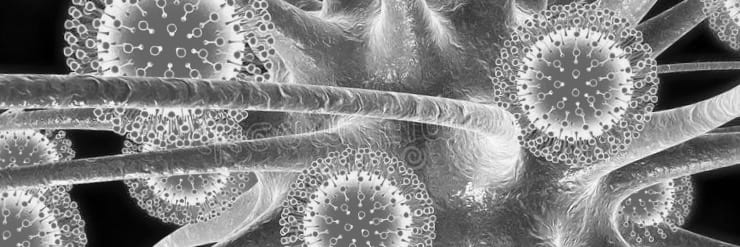

Examination of his mouth reveals these lesions:

Q 1. What is shown and what is the diagnosis?

Reveal answer

Koplik spots

Eponymous notoriety associated with Henry Koplik (1858–1927) following his 1896 description of ‘Koplik Spots‘

These are lesions on the buccal mucosa consisting of pinpoint greyish spots surrounded by bright red inflammation. They are considered pathognomonic of measles (aka rubeola), although they are only seen about 60% of the time, occuring just before the onset of the measles rash.

Measles is a highly infectious ssRNA virus (of the family Paramyxoviridaeand the genus Morbilivirus) spread by respiratory secretions via aerosolised droplets.

Worldwide, measles is still the 5th leading cause of death in children aged <5 years-old.

Q 2. What is the differential diagnosis?

Reveal answer

Australia has been officially measles free since 2009, so the ‘measles clinical syndrome‘ of cough, fever, conjunctivitis and rash actually has a low positive predictive value for measles in most settings. However, imported cases may still lead to outbreaks.The differential diagnosis of the ‘measles clinical syndrome’ includes:

- Viruses: rubella, parvoviruses, HHV6, flaviviruses, adeno-associated viruses, coxsackie, echoviruses

- Bacterial infection: streptococcus, meningococcocus, rickettsiae, spirochaetes (syphilis, Borreliaspp., Spirilium minus)

- Fungi: Coccidioides immitis

- Non-infectious or post-infectious causes: Kawasaki disease and its differentials

Q3. What are the typical clinical manifestations and course of this condition?

Reveal answer

Incubation period:

- 10 days (7-18 days)

Prodrome (2-4 days):

- ‘measles is misery’

- fever, malaise, poor appetite

- cough, coryza and bilateral conjunctivitis

- Koplik spots (~60%)

Clinical features

- Rash: maculopapular, non-itchy, non-vesicuar rash: starts behind the ears and hairline, spreads to the face, then the trunk, then the limbs. Becomes confluent, fades after about 3 days. Patchy areas of desquamation and brown-yellow discolouration my occur.

- Generalised lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly may occur.

Q4. What is the infective period?

Reveal answer

Measles is highly infectious and affected patients should be kept in isolation.

The infective period is from 1 day prior to the appearance of the rash, to 4 days after its onset.

Q 5. What are the possible complications of this condition?

Reveal answer

Most cases are measles resolve without complication — however fatal complications can occur, especially in young children, the malnourished and the immunocompromised.

Unlike rubella, measles is not teratogenic in pregnancy but may cause preterm births and stillbirths.

Common:

- Otitis media (9%)

- Other ENT and respiratory tract involvement — sinusitis, laryngotracheobronchitis, bronchiolitis, and pneumonitis.

- Diarrhoea (8%)

- Bacterial superinfection (e.g. pneumonia 6%)

- Exacerbation of Vitamin A deficiency leading to blindness in the malnourished.

Uncommon:

- Encephalitis (~1/1000, ~15% fatal) — more common in adults

- Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (1/100,000)

- Transverse myelitis

- Myocarditis

- Hepatitis

Q 6. What is subacute pansclerosing panencephalitits?

Reveal answer

A rare degenerative brain disorder that typically follows a case of uncomplicated primary measles, usually in a child younger than average at the time they contracted measles.

After 5 to 10 years myoclonus and focal neurological deficits occur, heralding progressive CNS degeneration resulting in death over a period of months to years. The condition is almost unheard of since the widespread adoption of measles vaccination.

Q 7. How should a suspected case be managed?

Reveal answer

Measles is a notifiable disease.

In the emergency department: triage to an isolation room and take droplet precautions.

Diagnostic tests to confirm/ exclude measles:

- Measles IgM serology: detectable from the first few days of infection (70% at day 3 of illness, about 100% at day 7) until 4-12 weeks. False positives and recent measles vaccination may confound the result.

- Paired measles IgG serology: the IgM result can be confirmed by testing for measels IgG within 7 days of rash onset, and repeating the test at 3-4 weeks.

- RT-PCR and EIA: RT-RCP may be used when serology is not diagnostic, to genotype the virus and trace its likely geographical origin. Can be performed on throat swabs, urine, blood, and nasopharyngeal aspirates.

- Tests for other pathogens in the differential diagnosis

Treatment:

- Supportive care

- Treat bacterial superinfection with antibiotics.

- Treat complications

- Vitamin A supplementation if malnourished

Public heath measures (see Q9):

- Public health authorities should be contacted as soon as possible to assist in confirming/ excluding the case as soon as possible and so that a potential outbreak can be contained.

Q 8. Describe the vaccine used in Australia. When is it given and what are the possible side effects?

Reveal answer

The MMR (measles-mumps-rubella) vaccine is a safe and effective vaccine adminstered as 0.5 mL SC/IM.

The MMR vaccine is a live attenuated vaccine that is 99% effective if two doses are administered at ≥12 months of age and at least 4 weeks apart. It is given at age 12 months and 18 months (previously 4 years) in Australia. During an outbreak the vaccine may be given to children as young as 6 months old. Live vaccines should not be given to the imunocompromised or the pregnant, and not within 4 weeks of another live vaccine.

Side effects include:

- Malaise, fever (5-15%) and/or a rash (5%) — most commonly 7 to 10 days (range 5–12 days) after vaccination and lasting about 2 to 3 days.

- Febrile seizures — 1 case per 3000 doses of MMR vaccine administered

- Anaphylaxis — very rare (<1 in 1 million doses), likely due to gelatin or neomycin anaphylactic sensitivity, not egg allergies.

- Other rare adverse events attributed to MMR vaccine include transient lymphadenopathy, arthralgia, parotitis and thrombocytopenia (usually self-limiting)

- It is uncertain whether encephalopathy occurs after measles vaccination — if so it is very rare.

In the near future, MMR may be replaced by MMRV in Australia, to also provide immunity against varicella (chicken pox).

The MMR vaccine is not causally linked with autism, autistic spectrum disorder or inflammatory bowel disease — most ‘scientific’ proponents of the hypothesis have retracted their claims and there is good evidence to refute it.

Q 9. What public health measures are required following the diagnosis of this condition?

Reveal answer

Public heath measures:

- Notify public health authorities

- Contact tracing

- Immunisation of susceptible contacts: MMR vaccine if <72 hours – (the vaccine has shorter incubation period than the wild-type virus) normal human IgG if >72 hours but less than 7 days

- Isolation of cases until 4 days after the onset of the rash (14 days for susceptible contacts not vaccinated witihin 72 hours of contact) – discharged patients should stay at home for this period.

References

- Australia Immunisation Hanbook (9th edition) — Measles.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles.

- Durrheim DN, Kelly H, Ferson MJ, Featherstone D. Remaining measles challenges in Australia. Med J Aust. 2007 Aug 6;187(3):181-4. [PMID: 17680748.]

- Immunise Australia Program. National Immunisation Program Schedule

- MacIntyre CR, McIntyre PB. MMR, autism and inflammatory bowel disease: responding to patient concerns using an evidence-based framework. Med J Aust. 2001 Aug 6;175(3):127-8. [PMID: 11548076.]

- Marx JA, Hockberger R, Walls RM. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice (7th edition), Mosby 2009. [mdconsult.com]

- Murch SH, Anthony A, Casson DH, Malik M, Berelowitz M, Dhillon AP, Thomson MA, Valentine A, Davies SE, Walker-Smith JA. Retraction of an interpretation. Lancet. 2004 Mar 6;363(9411):750. [PMID: 15016483.]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for epidemic preparedness and response to measles outbreaks. WHO/CDS/CSR/ISR/99.1. Geneva: WHO, 1999. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1999/WHO_CDS_CSR_ISR_99.1.pdf(accessed Jun 2006).

CLINICAL CASES

Tropical Travel Trouble

Chris is an Intensivist and ECMO specialist at The Alfred ICU, where he is Deputy Director (Education). He is a Clinical Adjunct Associate Professor at Monash University, the Lead for the Clinician Educator Incubator programme, and a CICM First Part Examiner.

He is an internationally recognised Clinician Educator with a passion for helping clinicians learn and for improving the clinical performance of individuals and collectives. He was one of the founders of the FOAM movement (Free Open-Access Medical education) has been recognised for his contributions to education with awards from ANZICS, ANZAHPE, and ACEM.

His one great achievement is being the father of three amazing children.

On Bluesky, he is @precordialthump.bsky.social and on the site that Elon has screwed up, he is @precordialthump.

| INTENSIVE | RAGE | Resuscitology | SMACC