Headache triggers

Help your patient identify the key food and non-food triggers that can contribute to their headaches

Identifying foods that trigger headaches

It is not commonly known that certain foods and dietary habits can trigger migraines and other headaches. As such, your patients may be unaware that the foods they are eating, or their eating habits, may be the cause of their pain.

Informing them of the foods and dietary habits that are associated with headaches should become part of your management routine. If your patient does experience food-related headaches, keep in mind that food triggers will vary from patient to patient.

It is also possible that certain foods in isolation will not provoke a headache, but when coupled with other triggers or stressors, a headache will result. For instance, eating a trigger food when a patient is already experiencing stress may increase the likelihood of getting a headache.

Foods that commonly trigger headaches include:

- Aged cheeses

- Yogurt

- Chocolate

- Cured meats and smoked fish

- Food preservatives (e.g., nitrates, nitrites, MSG, sweeteners)

- Certain vegetables (e.g., onions, pea pods, some beans, sauerkraut)

- Alcohol (particularly beer and wine)

- Yeast extracts and baked goods made with yeast

- Certain fruits (e.g., citrus, dried fruits, raspberries, red plums, papayas, passion fruit, figs, dates, avocados)

Revealing headache food triggers

Headache triggers can be revealed using an elimination diet or headache food diary

How to use an elimination diet to identify foods that trigger headaches

When trying to determine which foods may trigger a headache, patients shouldn’t experiment with their diet if they’re already experiencing other risk factors such as stress. Doing so will make it more difficult to identify if it was food, stress, or exhaustion that caused a headache attack.

So, how can you determine if there are certain foods which trigger headaches in your patient? Consider asking your patient to participate in an elimination diet.

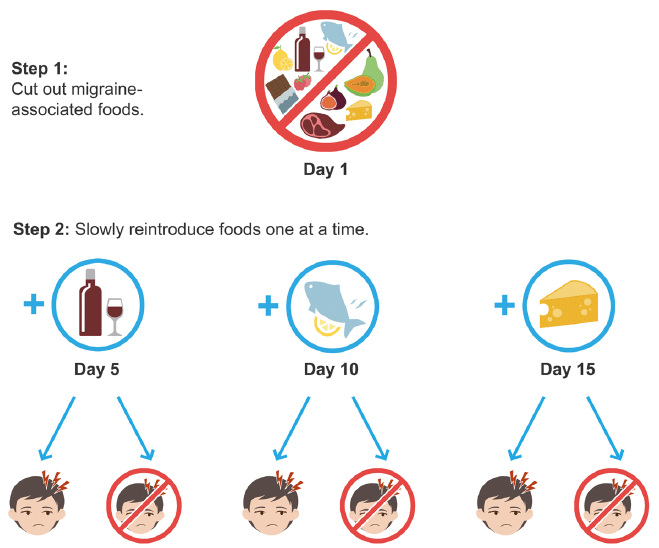

In an elimination diet, the patient cuts out foods and drinks that are known to trigger migraines, then slowly adds them back, one by one. If the patient’s headaches return, it may have been caused by the reintroduction of a certain food.

If your patient is aware of foods which can be problematic, they can watch for a headache after consuming these trigger foods. In the same way, if they skip meals, they might become aware of a relationship between food intake and headache occurrence.

Elimination diet to identify foods that trigger headaches. The elimination diet starts

with the removal of headache-associated foods, and then slowly reintroducing foods one at a time to determine if the reintroduced food is a headache trigger.

Using a headache diary to uncover dietary habits that may trigger headaches

There are dietary triggers that are unreliable, even deceptive. For instance, some dietary triggers may sometimes help headaches, but at other times may trigger a headache. Caffeine is one such trigger. Your patient may notice that caffeine helps them get rid of a headache but increasing caffeine intake may lead to an increase in headaches.

In this case, it might be useful to look more deeply into factors leading to the increase of caffeine. Perhaps your patient increased the amount of caffeine they consumed to overcome fatigue? This kind of information can be obtained from an observant patient using a headache diary.

A headache diary can help your patients discover and explore the relationships between certain foods, their dietary habits, and the appearance of headaches.

When your patient maintains a diary, and you review it with them diligently, you can discover a lot about their possible migraine causes and triggers.

Identifying non-food triggers for headaches

In addition to food, there are many other triggers that have been associated with headaches. These are the six most common non-food triggers:

- Hormones

- Exercise

- Stress

- Environment

- Sleep

- Oral structures

Hormone fluctuations

There is an increased incidence of headaches in women. The female sex hormones – oestrogen and progesterone – are linked to headaches. A decrease in oestrogen levels is a common headache trigger.

Menses is often associated with headaches because of decreasing oestrogen levels.

Hormone replacement therapy and oral contraceptives can exacerbate headaches or change the characteristics and frequency of headaches.

In pregnancy, headaches frequently increase during the first trimester then dissipate during the last two trimesters, possibly due to sustained high oestrogen levels.

Exercise

There is only limited evidence suggesting that exercise can influence the development of headaches. That said, a lack of regular exercise can trigger headaches, and regular exercise can potentially decrease headache frequency.

Exercise may reduce muscle tiredness and muscle tension, both of which can trigger headaches. As well, regular exercise improves energy levels, promotes better sleep, reduces stress, and improves body aches and pains. For instance, we know exercise benefits fibromyalgia body and muscle aches.

However, exercise is difficult for many to begin and sustain. Setting realistic goals and advocating for a simple program is helpful. For example, 20–30 minutes three times per week is a good starting point. Encourage a well-rounded program that includes aerobic activity, light weightlifting, and stretching.

Stress

As mentioned in the previous article, there is no clear evidence that stress causes – or is a direct factor – in the development of headaches. However, there is a perception that stress influences the frequency and severity of headache attacks.

Stress has been defined as a state when perceived demands exceed perceived resources. When we are stressed, our bodies respond by increasing cortisol levels (the stress hormone), but the possible role of cortisol in headache induction is unclear. Studies in this area have been difficult to perform.

Treatments such as cognitive behavioural therapy, biofeedback, meditation, and hypnosis can help with headache prevention.

Environmental factors

Some environmental factors can cause headaches. For example, reduced atmospheric pressure has been associated with headaches. Patients may note that their headaches increase with storms, rapid weather shifts, and seasonal changes.

Excessive exposure to sunlight (e.g., more than three hours) may trigger headaches in some patients, even if they do not experience photophobia.

Frequently, patients report that exposure to cigarette smoke and strong odours (e.g., perfumes or cosmetics) can trigger headaches.

Many patients also report that loud noises can trigger their headaches. Such data is often gained from headache diaries.

Sleep

The relationship between sleep and headaches is complicated. Headache pain can interfere with sleep in some patients, while other patients report that sleep can relieve their headaches. Patients also report that too little or too much sleep can provoke headaches.

Maintaining adequate sleep–wake cycles and practicing good sleep hygiene should be recommended for these patients.

This includes going to bed and waking each day at set times. Patients should avoid naps and trying to catch up on sleep during the weekends. If they do not fall asleep within 20 minutes of going to bed, they should get up and do something nonstimulating for 15–20 minutes, then try again. Furthermore, instruct patients to use their beds only for sleep and sex.

As well, remind your patients to avoid caffeine in the afternoon and evening, avoid eating and exercising in the evening, and limit alcohol intake. Regular exercise, a good diet, and incorporating relaxation techniques will help sleep hygiene.

Oral structures

Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dysfunction can lead to pain in the temporal region, clenching of the jaw, and grinding of the teeth (bruxism). These processes can occur while sleeping and become a trigger for headache, by activating the trigeminal nuclear complex. This is called nocturnal parafunction.

Clinical signs might include tenderness of the TMJ and the presence of trigger points in either the masseter or temporalis muscles.

For bruxism, clinical signs include rounding of the teeth and tenderness at the mastoid processes. Specially designed and fitted oral appliances can mitigate these issues and require consultation with a dentist.

This is an edited excerpt from the Medmastery course Headache Masterclass by Robert Coni, DO, EdS, FAAN. Acknowledgement and attribution to Medmastery for providing course transcripts.

- Coni R. Headache Masterclass. Medmastery

- Coni R. Clinical Neurology Essentials. Medmastery

- Simmonds GR. Neurology Masterclass: Managing Common Diseases. Medmastery

- Simmonds GR. Neurology Masterclass: Managing Emergencies. Medmastery

References

- The International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd edition

- Young WB. The Stigma of Migraine. Practical Neurology. 2018; 17: 23–26

- Turner DP, Jchtay I, Lebowitz A, et al. Perceived migraine triggers. Practical Neurology. 2018; 17: 37–40

Neurology Library: Headache – History, Examination and Investigation

- Coni R. Characterising headache. LITFL

- Coni R. Headache history. LITFL

- Coni R. The headache diary. LITFL

- Coni R. Headache triggers. LITFL

- Coni R. Physical examination. LITFL

- Coni R. Neurological examination. LITFL

- Coni R. Headache and imaging. LITFL

- Coni R. Headache and laboratory tests. LITFL

Neurology Library

Robert Coni, DO, EdS, FAAN. Vascular neurologist and neurohospitalist and Neurology Subspecialty Coordinator at the Grand Strand Medical Center in South Carolina. Former neuroscience curriculum coordinator at St. Luke’s / Temple Medical School and fellow of the American Academy of Neurology. In my spare time, I like to play guitar and go fly fishing. | Medmastery | Linkedin |

BMBS (The University of Nottingham) BMedSci (The University of Nottingham). Emergency Medicine RMO at Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital Perth, WA. Interested in Medical Education and Emergency Medicine. Swimmer and frequent concert attendee.