Jean-Alexandre Barré

Jean-Alexandre Barré (1880-1967) was a French neurologist.

Barré was renowned for his meticulous clinical examination, pioneering work in neuro-otology and vestibular disorders, and influential contributions to neurological semiology.

A student of Joseph Babinski (1857–1932) and an admirer of Jean-Martin Charcot (1825–1893), Barré combined a strong tradition of clinical neurology with a highly analytical and practical approach.

Appointed Professor of Neurology at the University of Strasbourg in 1919, Barré led a highly productive academic career spanning three decades. He published more than 800 scientific papers, founded the Revue d’Oto-Neuro-Ophtalmologie, and trained generations of neurologists from France and abroad. A passionate clinician, gifted teacher, and lover of classical music, Barré remained active in the scientific community despite suffering a disabling stroke in 1953. He died in Strasbourg in 1967, leaving a lasting legacy in clinical neurology.

Throughout his career, Barré developed a number of widely used neurological examination techniques, including the Barré test and Barré sign for subtle pyramidal deficits, and described the Barré–Liéou syndrome of cervical sympathetic dysfunction.

He is best remembered as co-describer, with Georges Guillain (1876–1961) and André Strohl (1887–1977), of the acute paralytic neuropathy now known as Guillain–Barré syndrome, first reported in 1916.

Biography

- 1880 – Born May 25 in Nantes, France.

- Early 1900s – Medical studies in Nantes; subsequently moves to Paris for further training.

- 1912 – Publishes doctoral thesis Les ostéoarthropathies du tabès.

- Pre-WWI – Intern in Paris hospitals; studies under Joseph Babinski (1857–1932).

- 1914–1918 – Serves during World War I; Initially with front-line ambulance units; Later transferred to Neurology Centre of the 6th French Army under Georges Guillain (1876–1961). Awarded the Légion d’honneur for wartime service.

- 1916 – Co-publishes Le réflexe médico-plantaire (1916) and Sur un syndrome de radiculo-névrite avec hyperalbuminose du liquide céphalo-rachidien sans réaction cellulaire — landmark description of Guillain–Barré syndrome.

- 1919 – Professor of Neurology at the University of Strasbourg.

- 1919 – Describes Barré sign (leg manoeuvre) for detecting subtle pyramidal paresis.

- 1920 – Describes Barré finger-spread test for identifying subtle motor deficits.

- 1926 – Describes Barré–Liéou syndrome (controversial sympathetic cervical syndrome).

- 1937 – Publishes work on syndrome pyramidal déficitaire (deficient pyramidal syndrome); Barré test terminology established.

- 1939–1945 – Serves briefly at the front in WWII; later assigned to medical duties in Clermont-Ferrand (non-occupied zone).

- 1950 – Retires from the University of Strasbourg.

- 1953 – Suffers cerebrovascular accident (stroke) with resulting hemiparesis, while returning from a medical congress in Lisbon; continues to participate in scientific meetings despite disability.

- 1967 – Dies April 26 in Strasbourg, aged 86.

Medical Eponyms

Barré sign (1919)

Sign of pyramidal disturbance [*aka manoeuvre de la jambe]. The patient (lying prone) is unable to keep the lower leg vertical on the side of a pyramidal lesion when the knees are flexed.

La manoeuvre de la jambe was first described in 1919 by Barré in La Presse médicale

L’homme normal garde les jambes verticales très longtemps sans difficulté et sans effort marqué. Au contraire, lorsqu’il y a paralysie ou seulement parésie, par atteinte du faisceau pyramidal, on voit la jambe du côté intéressé s’abaisser. Suivant les cas, et d après l’intensité du trouble paralytique, la jambe tombe immédiatement sans s’arrêter dans sa chute, ou bien elle reste quelque temps verticale pour s’étendre progressivement et accomplit une chute plus ou moins lente, régulière ou saccadée…Chez d’autres sujets, atteints de parésie légère, la chute commence bientôt, puis s’arrête, et la jambe peut rester longtemps ainsi, faisant un angle ouvert sur la cuisse, à 120-140°

Fig. 1. Manœuvre de la jambe. – Premier temps – Elle est positive à droite et à un degré moyen; la jambe s’arrête, en effet, à mi-chemin, dans son mouvement de déflexion.

A normal human keeps their legs vertical for a very long time without difficulty or marked effort. Conversely, when there is paralysis or only paresis, due to damage to the pyramidal fasciculus, the leg on the affected side is seen to drop. Depending on the case, and the intensity of the paralytic disorder, the leg falls immediately without stopping in its fall, or it remains vertical for a while before gradually extending and performing a more or less slow, regular, or jerky fall. In other subjects with mild paresis, the fall begins soon, then stops, and the leg may remain like this for a long time, forming an open angle on the thigh, at 120-140°.

Fig. 1. Leg maneuver. – First stage – It is positive on the right and of moderate degree; the leg stops, in fact, midway through its deflection movement.

Guillain- Barré syndrome (1916)

An acute inflammatory paralytic neuropathy [*aka Landry palsy; Landry-Guillain–Barré–Strohl syndrome]

During World War I, while serving in the Neurology Centre of the 6th French Army, he collaborated with Guillain, Barré and Strohl defined the characteristic albuminocytologic dissociation that distinguished their syndrome from other paralytic conditions.

- Guillain G, Barré JA, Strohl A. Sur un syndrome de radiculo-névrite avec hyperalbuminose du liquide céphalo-rachidien sans réaction cellulaire. Remarques sur les caractères cliniques et graphiques des réflexes tendineux. Bulletins et mémoires de la Société médicale des hôpitaux de Paris, 1916; 40: 1462-1470

Barré-Liéou syndrome (1926)

Also known as a posterior cervical sympathetic syndrome. A controversial syndrome which is characteristic by an occipital headache, vertigo, tinnitus and blurred vision which is attributed to irritation of the cervical sympathetic chain by chronic cervical arthritis. First described in 1925 and 1926 by Barré, and further described in 1928 by Yang-Choen Lieou, a student of Barré’s in Strasbourg

- Barré JA. Un nouvel aspect neurologique de l’arthrite cervicale chronique: le syndrome cervicale sympathique postérieur. Soc d’ONO Fr de Strasbourg; 1925

- Barré JA. Sur a sympathic cervical syndrome postérieur et sa cause frequent, l’arthrite cervicale. Revue Neurologique. 1926; 1: 1246-1248

- Liéou YC. Syndrome sympathique cervical postérieur et arthrite cervicale chronique de la colonne vertebrale cervicale. Etude clinique et radiologique. These. Strasbourg, 1928

Controversies

Barré test

Despite the relatively prevalent reporting of Barré being one of the first people to describe pronator drift and the use of the term “Barré test” to refer to an arm drift test in the detection of a subtle hemiparesis; this eponym has been incorrectly attributed to Jean Alexander Barré.

It was, Giovanni Mingazzini (1859-1929) in his original paper in 1913 that described this sign as the tendency for downward drift of both the arms and legs when an organic hemiparesis may be present.

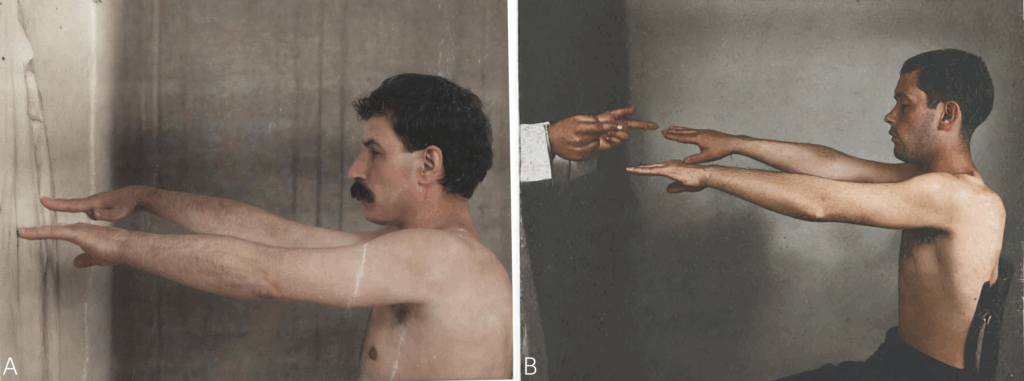

Il est un autre petit signe de l’hémiparésie organique, et que l’on peut rechercher en étudiant les mouvements du membre supérieur: c’est celui qui consiste en la flexion palmaire précoce de la main lorsque le membre supérieur est placé dans l’attitude du serment. Le procédé employé dans ce cas est le suivant: on demande au sujet d’étendre en avant les bras comme s’il avait à faire le signe du serment, les mains (flg. A) placées au même niveau que l’avant-bras et les doigts écartés. Pour détourner l’attention du sujet, il est bon de lui tenir les yeux fermés. Alors, au bout d’un temps qui peut varier d’une demi-minute à une minute, on voit que le membre affecté de parésie a une tendance à s’abaisser avant l’autre ou à osciller de côté et d’autre: les doigts de la main parétique sont animés de tremblements plus nets ou de légers mouvement d’abduction et d’adduction. Quelquefois, la main seule s’abaisse lentement.

There is another small sign of organic hemiparesis, which can be looked for by studying the movements of the upper limb: it consists of the early palmar flexion of the hand when the upper limb is placed in the attitude of the oath. The procedure used in this case is as follows: the subject is asked to extend his arms forward as if he had to make the sign of the oath, the hands (fig. A) placed at the same level as the forearm and the fingers spread apart. To divert the subject’s attention, it is good to keep his eyes closed. Then, after a time which can vary from half a minute to a minute, we see that the limb affected by paresis has a tendency to lower before the other or to oscillate from side to side: the fingers of the paretic hand are animated by more marked tremors or slight movements of abduction and adduction. Sometimes, the hand alone lowers slowly

The confusion likely arises from Barré’s description within his 1937 paper “Le syndrome pyramidale deficitaire”, where he also used photos demonstrating Mingazzini’s arm and leg tests but without referencing the original article.

B. Arm test of Mingazzini: from paper by Barré, 1937 [Epreuve du bras de Mingazziai – Le bras gauche s’abaisse verticallment; on peut noter également que l’extension des doigts est moins complète à gauche qu’à droite.]

Barré finger-spread test (1920)

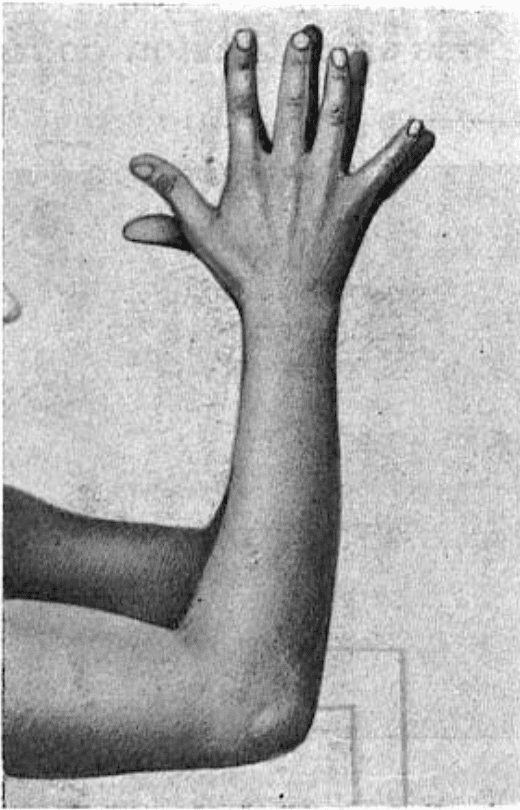

In terms of Barré describing a sign relating to the upper limb, in 1920 he did describe “Le signe de l’écartement des doigts” which was a sign relating to the spreading of the fingers of both hands to demonstrate slight paresis

Epreuve de l’écartement des doigts qui s’exécute en demandant au sujet d’écarter les doigts au maximum, en rapprochant les mains pour faciliter la comparaison, mais sans les mettre en contact, est fine et fidèle. Les doigts s’écartent moins du côté parésié; ils s’étendent moins complètement, la paume de la main est, de ce fait, plus creuse, et, l’écartement un peu réduit, diminue encore si l’on prolonge l’épreuve.

Fig. 11. — Epreuve de l’écartement des doigts: I’écartement aussi vigoureux que possible des doigts des deux mains rapprochées – mais non au contact – est nettement moindre à droite.

The finger spread test, performed by asking the subject to spread their fingers as far apart as possible, bringing their hands together to facilitate comparison but without bringing them into contact, is precise and accurate. The fingers spread less on the paresis side; they extend less completely, the palm of the hand is therefore more hollow, and, although the spread is slightly reduced, decreases further if the test is prolonged.

Fig. 11. — Finger spread test: the forceful spread of the fingers of both hands, brought together – but not in contact – is significantly less on the right.

Major Publications

- Guillain G, Barré JA, Strohl A. Le réflexe médico-plantaire: Étude de ses caracteres graphiques et de son temps perdu. Bulletins et mémoires de la Société médicale des hôpitaux de Paris, 1916; 40: 1459-1462.

- Guillain G, Barré JA, Strohl A. Sur un syndrome de radiculo-névrite avec hyperalbuminose du liquide céphalo-rachidien sans réaction cellulaire. Remarques sur les caractères cliniques et graphiques des réflexes tendineux. Bulletins et mémoires de la Société médicale des hôpitaux de Paris, 1916; 40: 1462-1470 [Guillain-Barré syndrome]

- Guillain G, Barré JA. Étude anatomo-clinique de quitanze cas de section totale de la moelle. Ann Méd. 1917; 2: 178–222

- Barré JA. La manoeuvre de la jambe. La Presse médicale 1919; 79: 793-795 [Barré sign]

- Barré JA. Le signe de l’ecartement des doigts. XXIVe Congres des Alienistes et Neurologistes, aout 1920. Revue Neurologique. 1920:942

- Barré JA. Sur a sympathic cervical syndrome postérieur et sa cause frequent, l’arthrite cervicale. Revue Neurologique. 1926; 1: 1246-1248 [Barré-Liéou syndrome]

- Barré JA. Le syndrome pyramidale deficitaire. Revue Neurologique. 1937; 67(1): 1-40 [Barré test]

References

Biography

- Thiebaut F. J. A. Barré (1880-1967). J Neurol Sci. 1968 Mar-Apr;6(2):381-2.

- Minkowski M. Jean-Alexandre Barré (1880-1967). Schweiz Arch Neurol Neurochir Psychiatr. 1968;102(2):376-9

- Koehler PJ, Bruyn GW, Pearce JMS. Neurological Eponyms. Oxford University Press 2000; 119-126

- Owecki MK, Skalski P, Magowska A. Jean-Alexandre Barré (1880–1967). Journal of Neurology 2018; 265: 987–989

- Drouin E, Poupart J, Hautecoeur P. Jean-Alexandre Barré: Babinski’s brilliant student. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2022 Mar;178(3):163-167.

- Fresquet JL. Jean Alexandre Barré (1880-1967). Historia de la Medicina

Eponymous terms

- Mingazzini G. Sur quelques “petits signes” des paresies organiques. Revue Neurologique. 1913; 20(2): 469-473

- Liéou YC. Syndrome sympathique cervical poste´rieur et arthrite cervicale chronique de la colonne verte´brale cervicale. Etude clinique et radiologique. These. Strasbourg, 1928. [Barré – Liéou syndrome]

- Pearce JM. Barré-Liéou “syndrome”. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004; 75(2): 319

- Hirose G. [The Barrés test and Mingazzini test -Importance of the original paper by Giovanni Mingazzini]. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2015;55(7):455-8

- Gorelov V. J-A Barré’s historic article “On posterior cervical sympathetic syndrome”: A translation from French. Cephalalgia. 2020 Oct;40(11):1261-1265.

Eponym

the person behind the name

Physician in training. German translator and lover of medical history.

Thank you very much for your excellent elucidation of the real facts in the background of this confusing area of “Barre-Mingazzini’s test “.