Should we use an “aerosol box” for intubation?

Editor’s note: Dr Albert Chan (@gaseousXchange) is an anaesthetist and simulation expert based in Hong Kong, with extensive experience in the use of simulation for airway management and COVID-19 disease. See COVID-19 airway management: better care through simulation. See the Editor’s addendum at the end of the post for updates on the aerosol box for intubation since this post was first published.

Introduction

Reports of healthcare workers (HCW) getting infected, and even dying, during the COVID-19 pandemic are disturbing and tragic. The risk posed to HCW during aerosol generating procedures (AGPs) such as intubation is significant (Fowler et al., 2004), especially when compounded by the rapidly diminishing availability of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). Health organisations must strive to ensure HCW safety while they provide patient care. Innovation may help address this issue.

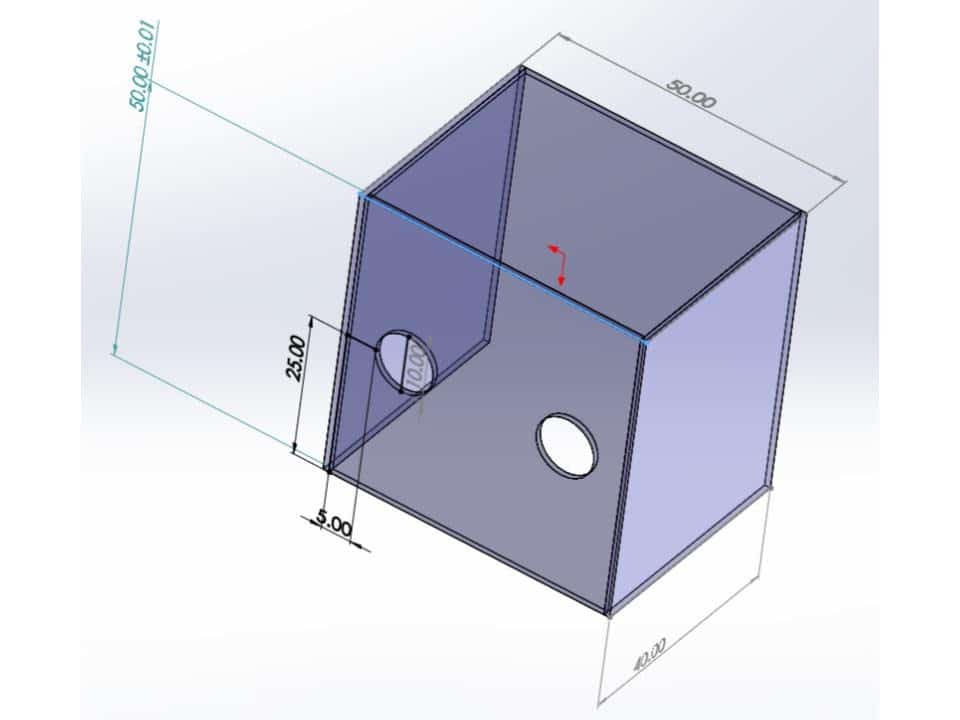

One such high profile innovation is the Aerosol box (Lai, Hsien Yung (Mennonite Christian Hospital, Hua Lian, 2020). It can be made using acrylic or transparent polycarbonate sheet with the dimensions as depicted below. It has been described in NEJM as having possible utility in preventing cough dispersion of particles on the laryngoscopist. (Canelli, Connor, Gonzalez, Nozari, & Ortega, 2020).

Interest in how this device may play a role in protecting the laryngoscopist has led to rapid dissemination of this simple contraption, through social media in particular. While the efforts of innovators to improve the safety of patient care, concerns about the usability and effectiveness of this device remain.

Simulation testing and findings

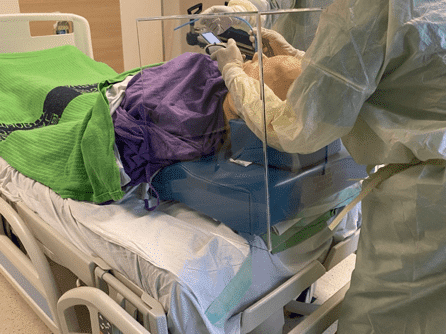

Using simulation to test medical innovations has been well described (Madani et al., 2017) – our group used in-situ simulation to test the utility of an identical “Aerosol Box” within our context of airway management in the ICU for suspected/confirmed COVID-19 cases.

The respective scenario designs are as follows:

- a Covid-positive patient, with normal body habitus and normal airway features, has failed all non-invasive methods of oxygenation and is in marked respiratory distress and hypoxia requiring intubation for ventilatory support in the ICU.

- a Covid-positive obese patient, with features of difficult intubation, has failed all non-invasive methods of oxygenation and is in marked respiratory distress and hypoxia requiring intubation for ventilatory support in the ICU.

Teams of 2 intensivists and 2 intensive care nurses is to intubate the patient using the “Aerosol Box” for protection in the AIIR. We debriefed the teams after the scenario. Below is a summary of the comments:

Pros:

- Perhaps good for anti-splash or direct cough from patient into face of the proceduralist (Canelli et al., 2020)

- May work for uncomplicated elective intubations – however, if the airway is not difficult and patient is well paralyzed for intubation with a clear team plan and well-trained coordination, the utility of the box may be of limited value.

Cons:

- Despite named “Aerosol Box”, it in fact does not protect against aerosols and may be a bit of a misnomer. An aerosol is a suspension of small particles (0.001 to 100uM), that may carry live virus for up to 3 hours (van Doremalen et al., 2020), is potentially generated during the process of tracheal intubation and has potential for long-range transmission to assisting personnel (Fowler et al., 2004). There is currently no evidence that the box prevents dispersion of aerosols

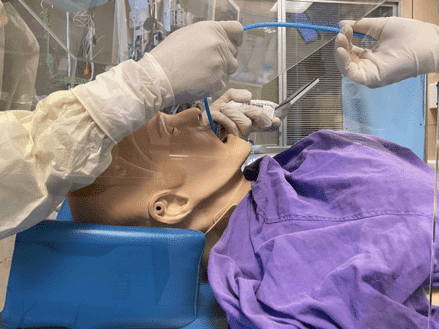

- It is limited for certain body habitus — will not fit the obese; moreover if you have to ramp up the patient (for a patient in respiratory failure or an obese patient), you will not be able to have space to manipulate the laryngoscope or the bougie within the box, and railroading an endotracheal tube into the airway is difficult. Ergonomically, the proceduralist will be levering with the laryngoscope, as his hands are far above his elbows and potentially lead to dental injury and difficult intubation (see images below). It is very difficult to insert a hyperangulated blade for difficult intubation with the box in place.

- It may also not work for patients with short neck, because it increases the distance from the proceduralist to the airway, and it will be ergonomically difficult to manipulate airway equipment

- Staff assisting the proceduralist may not be protected from aerosols or splash, especially if failed intubation/LMA and need to proceed to BVM (dispersion of aerosols during BVM is likely to be caudad even for the experienced (Chan et al., 2018))

- It is quite crowded in the box, and used equipment will easily contaminate the box as well as assisting staff.

- The box is bulky itself, and it is difficult for assisting staff to hand equipment to the proceduralist without contamination of themselves

- The box is also quite heavy and rigid, if handled inappropriately, especially in a chaotic situation with a crashing patient, may fall off the bed and potentially injure patient or staff.

- In a smooth intubation it might work, but for a difficult airway or failed intubation, it is a physical barrier to subsequent management (e.g. transition to rescue oxygenation with supraglottic airway device or an emergency surgical airway), will increase the cognitive load of the staff; and the risk of subsequent contamination may be even higher than normal, because the interior surface of the box will be heavily contaminated not only because of the splash, but also because of the insertion and removal of airway equipment within a confined space. If staff does not take precautions in removing, will lead to cross-contamination – this could well happen in an airway crisis or emergency situation when staff may have to urgently remove the box.

Conclusions

The take home messages from simulation testing of the aerosol box are:

- The aerosol box concept was useful in that it provoked ideas and discussion on protecting staff during performance of AGP, especially in the face of the diminishing supply of PPE.

- The model of crowd-sourcing for further improvements may also be useful for the future development of this innovation. (https://www.aerosolblock.org)

- Well-designed simulations as part of usability testing should always be used to test medical innovations prior to implementation in patients, for staff and patient safety reasons. “Face validity” alone should not be the basis of innovation adoption.

- It must be noted that there is a current paradigm shift from early intubation in the early phase of the pandemic, to intubation after failed non-invasive ventilation methods – thus patients who require intubation will be lot sicker, teams should stick with their best trained practice and PPE for managing the airways.

- For the current design of the widely disseminated “Aerosol box”, cons outweigh the pros in critically ill patients.

Recommendation

The “aerosol box” should not currently be used for intubation in most settings and is poorly suited to the management of critically ill patients. Further testing of the safety and effectiveness of the device is required. Clinicians should focus on using appropriate airborne/ contact precautions in accordance with local institutional polices and use recommended airway management strategies (e.g. Safe Airway Society COVID-19 Guidelines).

References

- Canelli, R., Connor, C. W., Gonzalez, M., Nozari, A., & Ortega, R. (2020). Barrier Enclosure during Endotracheal Intubation. New England Journal of Medicine, (April 3). https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2007589

- Chan, M. T. V., Chow, B. K., Lo, T., Ko, F. W., Ng, S. S., Gin, T., & Hui, D. S. (2018). Exhaled air dispersion during bag-mask ventilation and sputum suctioning-Implications for infection control. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-18614-1

- Fowler, R. A., Guest, C. B., Lapinsky, S. E., Sibbald, W. J., Louie, M., Tang, P., … Stewart, T. E. (2004). Transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome during intubation and mechanical ventilation. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 169(11), 1198–1202.

- Lai, Hsien Yung (Mennonite Christian Hospital, Hua Lian, T. (2020). Aerosol Box. Retrieved from https://sites.google.com/view/aerosolbox/home?authuser=0

- Madani, A., Gallix, B., Pugh, C. M., Azagury, D., Bradley, P., Fowler, D., … Aggarwal, R. (2017). Evaluating the role of simulation in healthcare innovation: Recommendations of the Simnovate Medical Technologies Domain Group. BMJ Simulation and Technology Enhanced Learning, 3(Suppl 1), S8–S14. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjstel-2016-000178

- van Doremalen, N., Bushmaker, T., Morris, D. H., Holbrook, M. G., Gamble, A., Williamson, B. N., … others. (2020). Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. New England Journal of Medicine.

Editor’s addendum

by A/Prof Chris Nickson, last updated 6 July 2020

While social media has played a part in the rapid dissemination and early adoption of innovations such as the aerosol box, social media has also had a role in promoting skepticism of new devices. Examples include tweets by airway management thought leaders including @lauraduggan, @nicholaschrimes, and @rosshofmeyer. The basis for this blogpost was originally a Twitter thread by Albert Chan (@gaseousXchange) himself.

Subsequently, our colleagues in Toronto (@AdvPerformHD), including Dr Andrew Petrosoniak and Dr Chris Hicks, published an excellent Twitter thread (and subsequently created a webpage) detailing their simulation-based testing of an “aerosol box”, where they also recommended AGAINST the use of the “aerosol box” in their setting:

Concerns that the “aerosol box” would be implemented into clinical practice without adequate testing led us to conducted a cross-over simulation study (involving experienced anaesthetists) to assess the impact of two different types of “aerosol boxes” on intubation (Begley et al, 2020).

- Begley J, Lavery K, Nickson C, Brewster D. (2020), The aerosol box for intubation in COVID‐19 patients: an in‐situ simulation crossover study. Anaesthesia. Accepted Author Manuscript. doi:10.1111/anae.15115

The key findings were that:

- intubation time was prolonged with aerosol boxes, to an extent that it risks patients developing hypoxaemia.

- intubation times with no aerosol box was significantly shorter than with the early‐generation box ((median (IQR [range])) 42.9 (32.9‐46.9 [30.9‐57.6]) seconds vs. 82.1(45.1‐98.3 [30.8‐180.0]) seconds, p=0.002) and the latest‐generation box (52.4(43.1‐70.3 [35.7‐169.2]) seconds, p=0.008).

- No intubations without a box took more than one minute, whereas 14 (58%) intubations with a box took over one minute and 4 (17%) took over two minutes (including one failure).

- first pass success is less likely with aerosol boxes

- Without an aerosol box, all anaesthetists obtained first‐pass success.

- With the early‐generation and latest‐generation boxes, 9 (75%) and 10 (83%) participants obtained first‐pass success respectively

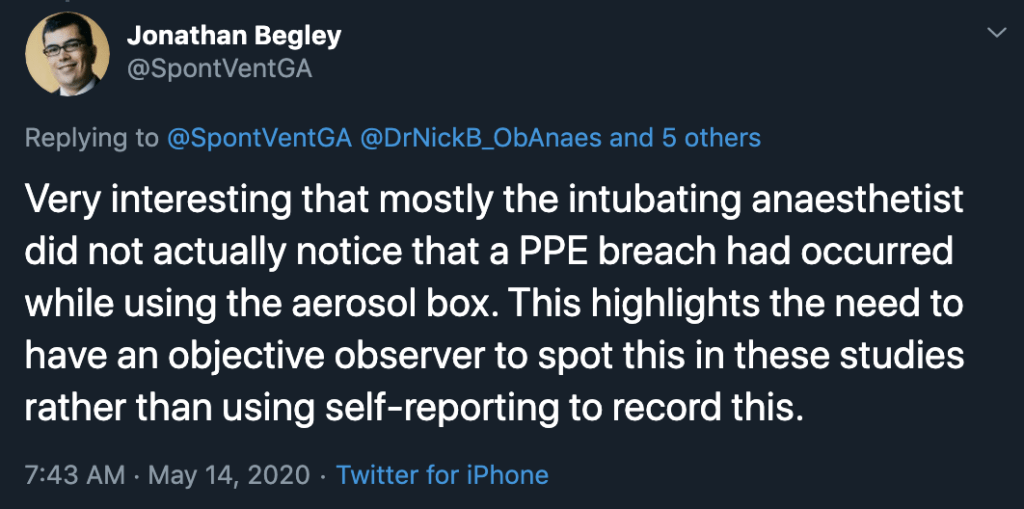

- use of aerosol boxes risks breaches of protective personal equipment placing clinicians at risk of infection.

- One breach of personal protective equipment occurred using the early‐generation box and seven breaches occurred using the latest‐generation box.

- See here for photos of examples of the PPE breaches (there were no PPE breaches when an aerosol box was not used).

- anaesthetists using aerosol boxes said they experienced discomfort, increased cognitive load, and restricted movement among other concerns.

The onus is on those who seek to introduce innovations to test whether they are safe and effective. Of note, there is a lack of evidence that aerosol boxes even do what they are meant to do – reduce the risk of infection transmission. In our efforts to improve patient care we must guard against MacGyverism and Gizmo Idolatry.

After all that, Simpson et al (2020) recently published an in-situ simulation of tracheal intubation performed in an intensive care room using five proposed aerosol containment devices. They quantified airborne particle exposure of the ‘laryngoscopist’ and found that exposure may be paradoxically increased with an “intubation box”. Dr Laura Duggan has discussed this study, its interpretation, and its implications, in her LITFL post, Perhaps something isn’t always better than nothing.

- Simpson JP, Wong DN, Verco L, Carter R, Dzidowski M, Chan PY. Measurement of airborne particle exposure during simulated tracheal intubation using various proposed aerosol containment devices during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anaesthesia. 2020. doi:10.1111/anae.15188

Meanwhile, we are reminded that social media is a double-edged sword. We argue that social media can have an important role in the rapid dissemination of useful information in the context of a pandemic in Anaesthesia here. The rapid dissemination of the findings of our study led by Dr Jonathan Begley (@SpontVentGA) is a case in point. Sometimes, ‘going viral’ might even save lives.

SARS-CoV-2

novel coronavirus of COVID-19

Dr Albert Chan MBBS, FHKCA, FHKAM (Anaesthesiologist), FANZCA is Associate Consultant, Department of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, Prince of Wales Hospital and Clinical Assistant Professor (Honorary), Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong | @gaseousXchange |

I have some notes:

1) I don’t have VL so aerosol box is not an option

2) external laryngeal manibulation is difficult

3) in critical situation, I don’t like to try new things

Hey Guys,

If you need an aerosol box to protect yourself from aerosols during intubation you are really doing this incorrectly.

The protected controlled intubation steps are simple: Intubate early before you lose apneic reserve and PARALYZE unless there is a contraindication (which is pretty well unheard of these days)=no cough.

The approach to this came from SARS 2003 and practiced for MERS-both more deadly.

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1a6mXai4RqQ7BexbdK6AFoSvzxxUjvsT4

Great summary of issues surrounding an ‘intubation box’ thank you @precordialthump

I think airway managers are creating boxes because they don’t trust their PPE to protect them.

Love @AdvPerformHD has broken down the issues so well.

Keep up such great work

@drlauraduggan

Thank you!! I fully agreed with not using the box. Blinded by a shiny object – the less experienced people are the more fascinated they become with box. The NEJM letter showed that the box trapped secretion after cough – wow – do we need a video for that?? I am glad for the simulation that exposes the limitations so obvious to experienced critical care providers!

Thank you for the detailed review Dr Chan. Some of the issues that you identified are present with the original design of the intubation box, but please take a look at some of the other designs available. Although you are correct that the boxes do not block aerosols, they definitely help contain them, and will block expelled droplets. There are designs that will perform well with bariatric patients, allow good access, do not move you farther away, are light weight, etc. Many of the issues that you identified have been resolved. It would be a shame for providers to miss out on this simple, inexpensive, shield because of the design flaws in the original. For a more up to date design, check out aerosolbox.us

“that may carry live virus for up to 3 hours (van Doremalen et al., 2020)” This is NOT what their study found but it widely misclaimed to have. They found that aerosols remained in static air at 3 hours at >90% of initial levels, they stopped measuring at 3 hours, aerosols remain in the non negative pressure rooms for at least 3 hours and given the rate of decay in the study likely many many times that.

Hi Robert

van Doremalen et al (2020) (https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMc2004973) experimentally produced aerosols containing SARS-CoV-2 virions. They did this using a three-jet Collison nebulizer that fed into a Goldberg drum to create an aerosolized environment.

They found that the virus remained infectious in tissue-culture assays, with only a slight reduction in infectivity, even after a 3-hour period of observation in this artificially aerosolised environment.

I believe that the statement about aerosols “that may carry live virus for up to 3 hours” is correct.

Regards

Chris

As a Pediatric Emergency Medicine physician I think the existing Lai intubation box ideas are impractical for my needs. One design I like better has a PVC frame with a clear dropcloth over it. The design provides better access and is less complex to construct.

I have an alternate design for adults or kids that solves many of the issues identified above and others issues that have not been identified. I have a simple, free, DIY intubation/respiratory box that is quickly made, immediately scalable for large quantities, disposable to prevent crosscontamination, provides easy maneuverability, chest access during CPR, protects ALL OF STAFF (not just the laryngoscopist). The design uses, a corrugated box, a large clear bag and CONTINUOUS SUCTION.

In my opinion, the flaws of the prior designs are that the arm holes are very restrictive especially if you do not have video laryngoscopy capabilities. Also, prior designs do not provide an enclosed chamber to trap particles on both ends. Using draped plastic your arms are not restricted by the arm holes. By always using continuous suction, you create a negative pressure chamber to reduce the viral bioburden inside the box. A negative pressure room protects those outside the room, but my design protects those inside the resuscitation room. It can also be used for routine neb treatments and bridge therapies that may help prevent intubation. (Also great for high risk enclosed exposures during transport and EMS)

For those already with Lai type intubation boxes, I suggest you your cut-outs larger on the top end, drape plastic over any openings and always have continuous suction running to suck out the bad air and displace it with cleaner air. For those that don’t have shiny boxes, or if you recognize the benefits for expanded uses of mini-negative pressure chambers, please see https://splashcap.com/covid-19-ppe/ . Here you will find instructions on the material and technique on how to make you own useful and simpler boxes. If you like the idea, please pass on to others in your networks to help provide another barrier to keep our colleagues safe. Please feel free to contact me if you have any comments or questions.

Joseph Schultz, MD

I have used the aerosol intubation box for many patients and used it successfully. Yes there is some glare, especially because I also don a PAPR for my intubations. And yes, the ergonomics are bit challenging. But it has not prolonged my intubation time by more than a few seconds. I have not yet had a morbidly obese patient with Covid, but if I have to intubate one, then this is the patient group that I will consider to forgo the intubation box.

I also cover the opposite open end of the box with a clear plastic drape, so it is completely closed system. I cannot be certain if it does reduce the aerosolization, but it definitely helps contain the droplets. With alarming number of deaths of health care workers, I would be cautious to advise the medical community against an intervention that could help contain the spread and minimize risk of exposure to the proceduralist and other personnel in the room.

I think the aerosolbox has all the problems described by Dr. Chan.

I am developing a prototype, which solves most of these problems, namely, the problem of hands, the concentration of aerosols inside the box and the problem of contamination of the team. My innovative prototype is totally different from Dr. Lai’s aerosolbox, and inside the box six hands can work simultaneously (the hands of the proceduralist, and two assistants, one on each side). My device is applicable to all situations in which it is necessary to approach the airway (Anesthesia, ICU, endoscopy, stomatology). It will soon be available, and I will inform you here.

Meanwhile, I inform you here of another device created by me.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y7ru0etuh2Y

best regards

Reinaldo Almeida, MD, sénior anesthesiologist