Trauma! Penetrating Abdominal Injury

aka Trauma Tribulation 025

Two patients are rushed into the ED following a violent encounter. The first patient, a teacher, was in altercation with a man who stabbed him in the anterior abdomen with a knife. His friend, another teacher, came to his assistance. He was shot in the anterior abdomen by another assailant standing behind the man wielding the knife.

Can you deal with the aftermath of this parent-teacher meeting gone horribly wrong?

Questions

Q1. Which wounds should be considered potential penetrating abdominal wounds?

Answer and interpretation

Any wound between the nipple line (T4) and the groin creases anteriorly, and from T4 to the curves of the iliac crests posteriorly.

If the wound was caused by a projectile, then a penetrating abdominal injury could result from an entry wound in almost any part of the body.

Q2. What are the 4 important regions of the abdomen to consider in penetrating injury?

Answer and interpretation

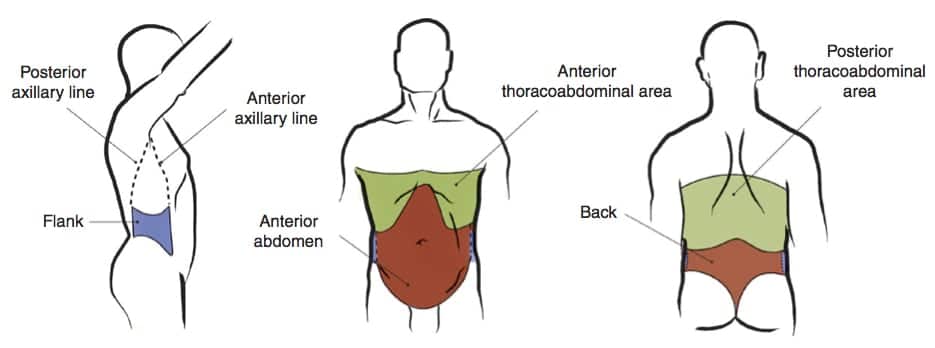

These are the 4 regions of the abdomen to consider in penetrating injury:

- Anterior abdomen: — Between the anterior axillary lines; bound by the costal margin superiorly and the groin crease distally.

- Thoracoabdominal area — The area superiorly delimited by the fourth intercostal space (anterior), sixth intercostal space (lateral), and eighth intercostal space (posterior), and inferiorly delimited by the costal margin (definitions vary — a pragmatic approach is to use the nipple line as the upper boundary… in non-obese men at least!). Injuries in the region increase the likelihood of chest, mediastinal, and diaphragmatic injuries.

- Flanks — From the inferior costal margin superiorly to the iliac crests; bound anteriorly by the anterior axillary line and posteriorly by the posterior axillary line.

- Back — Between the posterior axillary lines extending from the costal margin to the iliac crests.

Q3. What are the indications for emergency laparotomy in penetrating abdominal trauma?

Answer and interpretation

- Peritonism

- Free air (in stab wounds may represent the introduction of external air rather than gastrointestinal perforation)

- Evisceration

- Hypotension (hemodynamic instability)

- Gunshot wound traversing peritoneum or retroperitoneum

- GI bleeding following penetrating trauma

- penetrating object is still in situ (risk of precipitous haemorrhage on removal)

Neither of your patients require emergency laparotomy based on your team’s primary surveys. Your team is progressing with their assessments and stabilising the patients.

Q4. What are the key questions to ask that guide further assessment and management of patients with penetrating abdominal trauma?

Answer and interpretation

In patients with penetrating abdominal injury, if immediate emergency laparotomy is not indicated then once the patient is stabilised we have to answer 2 questions that act as key decision nodes guiding our approach:

- does the wound penetrate the peritoneum?

- is there intraperitoneal organ injury?

Q5. How can you assess for peritoneal penetration in the patient with the abdominal stab wound, and what do the results necessitate?

Answer and interpretation

Only two-thirds of anterior abdominal stab wounds violate the peritoneum, and only half of these require operative intervention.

Assess for peritoneal penetration:

- local wound exploration — involvement of abdominal fascia is considered a positive result.

- CXR — peritoneal penetration is confirmed by free air under diaphragm, but absence of free does not rule it out

- Ultrasound —peritoneal penetration is confirmed by free fluid in the abdomen or evidence of abdominal fascia violation, but absence of these findings does not rule it out

- DPL — this is invasive and not specific for injuries requiring operative intervention. It may be use if ultrasound is unavailable and some advocate it for thoracoabdominal wounds. A positive result is >100,000 RBCs/hpf for anterior abdominal wounds, and 10,000 RBCs/hpf for thoracoabdominal wounds that are at higher risk of diaphragmatic injury. Some suggest using the lower threshold for anterior wounds as well, but this leads to a higher negative laparotomy rate.

If the fascia is intact (i.e. all of the above are confirmed negative, excluding peritoneal penetration):

- the wound can be cleaned and closed in the ED.

- If there are no other concerns the patient may be discharged.

If local wound exploration is in adequate and abdominal fascia injury cannot be excluded, or there is evidence of peritoneal penetration, then further investigation is needed to assess for intraperitoneal injury.

Q6. How can you assess for intraperitoneal injury in the patient with the abdominal stab wound, and what do the results necessitate?

Answer and interpretation

There are two options for identifying intraperitoneal injury if emergency laparotomy (see Q2) is not indicated:

- CT abdomen

- direct laparoscopy

CT abdomen (97% sensitive for peritoneal violation) is usually performed:

- look for evidence of peritoneal penetration and intraperitoneal injury:

— free air

— free fluid

— bowel wall thickening

— wound tracts adjacent to a hollow viscus

— solid organ injury

An alternative in some centers is direct laparoscopy, which is often performed for left thoracoabdominal wounds due to the risk of diaphragmatic injury (17%) and may allow repair.

If the peritoneum is penetrated, then the options are:

- laparotomy if there is intraperitoneal injury requiring operative repair (e.g. colon perforation), or

- observation with serial examination +/- FAST scans and serial full blood count checks for 24 hours if no intraperitoneal injury

(some injuries such as those the pancreas or a hollow viscus may not be detectable initially and may present later)

The option of selective non-operative management of anterior abdominal wounds is made based on the type of intraperitoneal inury and the experience of the trauma center.

Q7. How does your approach differ for penetrating injury due to gunshot wounds?

Answer and interpretation

The same two questions need to be answered:

- Does the wound penetrate the peritoneum?

- Is there intraperitoneal organ injury?

Compared to stab wounds abdominal gunshot wounds are more likely to penetrate the peritoneum (80%), and those that do are more likely to cause intraperitoneal injury (90%). Also, bullets an similar missiles are higher velocity and may richocet resulting in unpredictable wound tracts. This modifies the approach compared with stab wounds.

These are the differences in assessment:

- Local wound exploration should only be performed if the projectile was low velocity with a presumed tangential tract.

- CT abdomen with IV contrast is the optimal method for determining both peritoneal penetration and intraperitoneal injury unless emergency laparotomy is indicated (see Q2). It also identifies the missile pathway. Triple contrast is used if suspected gastrointestinal injury.

- DPL is an alternative for detecting intraperitoneal injury if CT is not available, using a threshold of 5 to 10,000 RBCs/hpf for a positive result.

- Direct laparoscopy is also useful for left thoracoabdominal gunshot wounds.

These are the differences in management:

- traditionally all gunshot wounds with peritoneal penetration undergo laparotomy.

Of course, anyone who has done a MCQ test knows there is no such thing as all, always, or never… In centers experienced with the management of GSWs selective non-operative management may be used (as for stab wounds in Q5), such as isolated liver injuries (RUQ) and patients who remain hemodynamically stable with no evidence of peritonism.

Q8. How useful is CT abdomen for detecting diaphragmatic injury?

Answer and interpretation

It varies according to how fancy the CT scanner is and the skill of the radiologist. In some centers sensitivity is as high as 95%. This still means some diaphragmatic injuries will be missed and patients require close observation and consideration of other tests (e.g. the surgeon’s eye-ogram).

Q9. Who should perform local wound exploration, how, and where?

Answer and interpretation

Local wound exploration of a penetrating abdominal wound is best performed by an trained, experienced surgeon or emergency doctor.

Local wound exploration of abdominal wounds can be performed in the ED as follows:

- universal precautions

- perform procedure under sterile conditions

- Local anesthesia is injected at the wound site

- The wound track is followed through the layers of the abdominal wall or until its termination.

- The goal is to identify the end point of the tract, this usually requires extension of the wound to allow adequate visualisation. Extend midline wounds vertically and lateral wounds laterally for best cosmetic results.

- A positive result is penetration of the posterior rectus fascia or the transversus fascia below the rectus line.

Exceptions include:

- Wounds overlying the rib cage — local exploration may cause a pneumothorax. These wounds should be explored in the operating theatre.

- The role of local wound exploration in back and flank wounds is controversial. Some argue that these regions that tracts are difficult to follow in these regions due to increased musculature and that exploration may be unreliable and/or precipitate bleeding. Others advocate for local wound exploration in these regions.

- If the wound cannot be adequately explored – due to factors like lack of patient cooperation, obesity, local haemorrhage or distortion — the patient should be admitted fro repeat examination or undergo laparotomy and surgical exploration in the operating theatre.

Check out the Emedicine article: Abdominal stab wound exploration

Q10. What special considerations are there for penetrating wounds of the back and flank?

Answer and interpretation

Assessment of these regions is difficult and management varies:

- up to 40% have intraperitoneal injuries and there is high risk of injury retroperitoneal structures

- dense musculature of the paraspinous region makes local wound exploration difficult

- clinical examination is unreliable and neither ultrasound nor DPL are able to adequately assess retroperitoneal injury

- CT abdomen with IV contrast is the investigation of choice

- Management varies between centers — conservative approaches take most wounds to the OT, less conservative approaches will use CT abdomen and serial observation as part of a selective non-operative management policy..

References

Textbooks and Journal Articles

- Biffl WL, Kaups KL, Pham TN, Rowell SE, Jurkovich GJ, Burlew CC, Elterman J, Moore EE. Validating the Western Trauma Association algorithm for managing patients with anterior abdominal stab wounds: a Western Trauma Association multicenter trial. J Trauma. 2011 Dec;71(6):1494-502. PubMed PMID: 22182859.

- Biffl WL, Kaups KL, Cothren CC, Brasel KJ, Dicker RA, Bullard MK, Haan JM, Jurkovich GJ, Harrison P, Moore FO, Schreiber M, Knudson MM, Moore EE. Management of patients with anterior abdominal stab wounds: a Western Trauma Association multicenter trial. J Trauma. 2009 May;66(5):1294-301. PubMed PMID: 19430229.

- Butt MU, Zacharias N, Velmahos GC. Penetrating abdominal injuries: management controversies. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2009 Apr 17;17:19. Review. PubMed PMID: 19374761; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2674409.

- Como JJ, Bokhari F, Chiu WC, Duane TM, Holevar MR, Tandoh MA, Ivatury RR, Scalea TM. Practice management guidelines for selective nonoperative management of penetrating abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 2010 Mar;68(3):721-33. Review. PubMed PMID: 20220426.

- Fildes J, et al. Advanced Trauma Life Support Student Course Manual (8th edition), American College of Surgeons 2008.

- Lawson, RB. Abdominal stab wound exploration. Emedicine, updated Jan 30, 2012 [accessed March 22, 2012]

- Legome E, Shockley LW. Trauma: A Comprehensive Emergency Medicine Approach, Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Marx JA, Hockberger R, Walls RM. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice (7th edition), Mosby 2009. [mdconsult.com]

- Resus.ME — Guidelines on penetrating abdominal trauma

Social media and other web resources

- Trauma Professional’s Blog — When can you close that stab wound?

- Trauma Professional’s Blog — How to read a stab wound

- Trauma Professional’s Blog — CT evaluation of stab wounds

- Trauma! Initial Assessment aA Q&A guide to the assessment and management of penetrating abdominal trauma, including stab wounds, gunshot wounds and different regions of the abdomen.nd Management

- Trauma Tribulation 031 — Little wound, Long Knife

CLINICAL CASES

Trauma Tribulation

Chris is an Intensivist and ECMO specialist at The Alfred ICU, where he is Deputy Director (Education). He is a Clinical Adjunct Associate Professor at Monash University, the Lead for the Clinician Educator Incubator programme, and a CICM First Part Examiner.

He is an internationally recognised Clinician Educator with a passion for helping clinicians learn and for improving the clinical performance of individuals and collectives. He was one of the founders of the FOAM movement (Free Open-Access Medical education) has been recognised for his contributions to education with awards from ANZICS, ANZAHPE, and ACEM.

His one great achievement is being the father of three amazing children.

On Bluesky, he is @precordialthump.bsky.social and on the site that Elon has screwed up, he is @precordialthump.

| INTENSIVE | RAGE | Resuscitology | SMACC