Ultrasound Case 094

Presentation

A 68 year old male presents 2 weeks post coronary artery bypass grafting. He describes continuing chest wall pain, increasing shortness of breath and poor exercise tolerance. You wonder whether this is a pericardial effusion have a look.

View 2: apical 4 chamber view

View 3: Longitudinal view left lower posterolateral chest wall

View 4: Longitudinal view right lower posterolateral chest wall

Describe and interpret these scans

IMAGE INTERPRETATION

Image 1: Parasternal long axis view.

There is a large left sided pleural effusion with associated lung collapse. There is no pericardial effusion.

Image 2: apical 4 chamber view.

This demonstrates the pleural effusion again, with no pericardial effusion.

Image 3: Longitudinal view left lower posterolateral chest wall.

The large pleural effusion is confirmed. There is fine echogenic material within the fluid. Lung is compressed / collapsed.

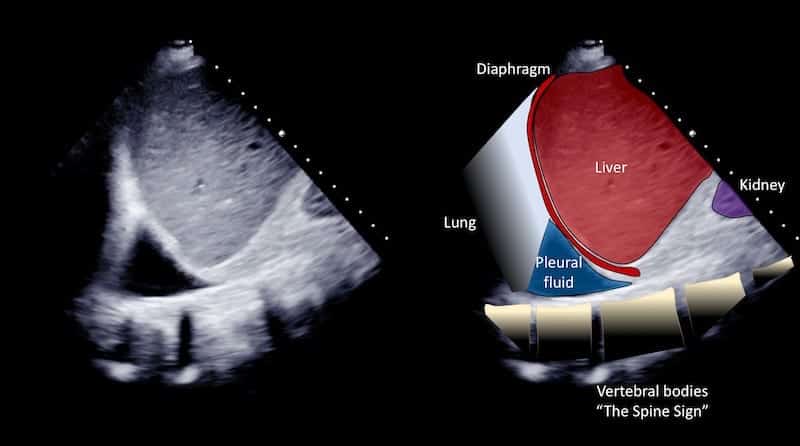

Image 4: Longitudinal view right lower posterolateral chest wall, using the liver as an acoustic window.

A small pleural effusion fills the costophrenic recess, and the vertebral bodies are seen deep to this.

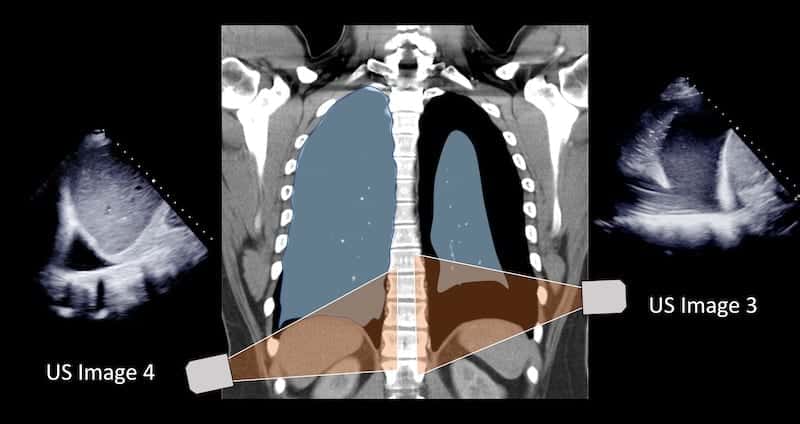

Image 5: CT comparison – understanding images 3 and 4

CLINICAL CORRELATION

Large left sided pleural effusion, small right sided pleural effusion

Differentiating pericardial and pleural effusion in the parasternal long axis cardiac view.

Both will had a hypoechoic fluid collection deep to the left ventricle.

Pericardial effusion should surround the heart (although loculated effusion can occur articularly post operatively). Pericardial effusion may compromise right sided chamber filling. Pericardial effusion spread is limited by the pericardium and ends anterior to the descending aorta (see image 1 and 2).

Pleural effusion is seen posteriorly only. It extends posteriorly to the descending aorta and along the vertebral bodies. Collapsed lung is often seen in the effusion. The effusion can be confirmed by exploring the costophrenic angle and chest wall posterolaterally.

Determining the volume of a pleural effusion using ultrasound. The simplest technique is to measure the depth of the deepest pocket of the effusion in cm, which may lie subpleurally (between the inferior lung surface and diaphragm) or laterally (between the lateral pleural surface and the chest wall). Multiply this number by 200 to get a very approximate volume in milliliters.

The “spine sign”.

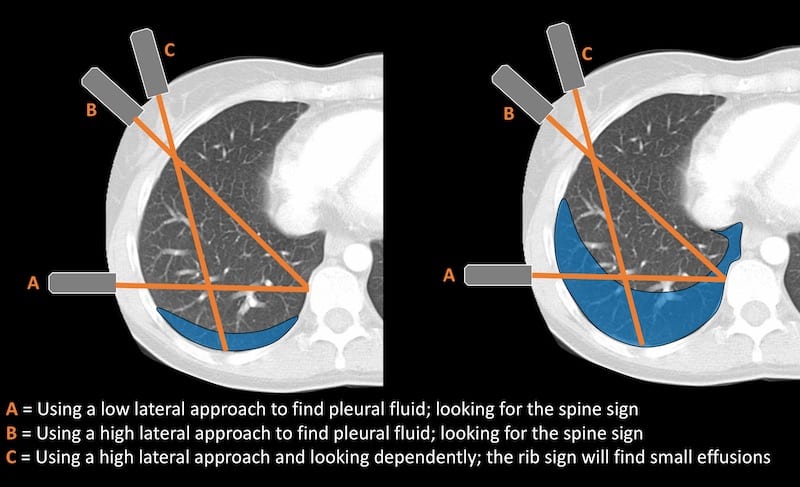

When assessing for a pleural effusion in the supine patient, particularly on the right side we use the liver as an acoustic window. Looking through the liver we can see the diaphragmatic recess the other side of the diaphragm (Images 3 and 4 demonstrate the “spine sign”).

To see the vertebral bodies the probe is directed medially, and looks at the diaphragmatic recess adjacent to the vertebral bodies. This is not the most dependent portion in a supine patient and small effusions will be missed. To assess for smaller effusions the probe should be directed to the most dependent part of the supine thoracic cavity. This means aiming toward the ribs rather than the spine (“C” on figure below). This will ensure small pleural effusions are not missed.

[cite]

TOP 100 ULTRASOUND CASES

An Emergency physician based in Perth, Western Australia. Professionally my passion lies in integrating advanced diagnostic and procedural ultrasound into clinical assessment and management of the undifferentiated patient. Sharing hard fought knowledge with innovative educational techniques to ensure knowledge translation and dissemination is my goal. Family, wild coastlines, native forests, and tinkering in the shed fills the rest of my contented time. | SonoCPD | Ultrasound library | Top 100 | @thesonocave |