Unlearning

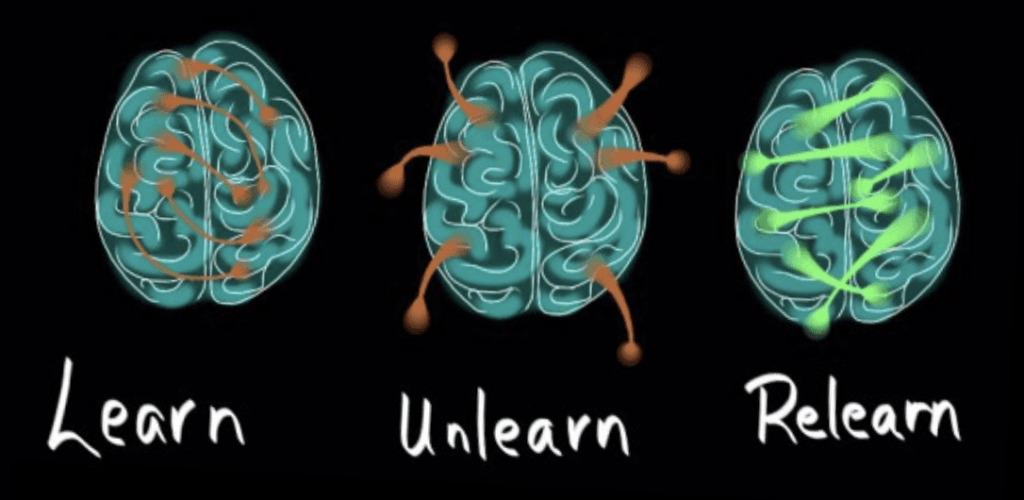

Unlearning is the process of abandoning or giving up knowledge, values or behaviour either unconsciously or deliberately (Coombs et al, 2013)

- Some alternate definitions make a distinction between unlearning and ‘forgetting’ (i.e. routine unlearning or ‘fading’), which is a passive unconscious process

- Alternative terms for unlearning have been used in different contexts, these include de-implementation, de-adoption, and de-diffusion

- Unlearning applies to both individuals and organisations. Individual learning (and unlearning) translates to the organisational level through social interaction and becomes part of ‘organisational memory’

Failure to “unlearn” pre-existing incorrect knowledge is a barrier to future learning and improvement

- Klein (2011) has proposed the ‘snake skin’ metaphor for understanding complex learning: as we outgrow our existing mental models, we need to shed them as our beliefs become more sophisticated

- Complex learning is not simply a matter of ‘packing in’ more facts, rules and procedures

- ‘Proactive interference’ occurs when prior learning makes learning new material more difficult

“Climbing the learning curve is only half the process… the other half is the unlearning curve.” — Solovy, 1999 “Knowledge grows, and simultaneously it becomes obsolete as reality changes. Understanding involves both learning new knowledge and discarding obsolete and misleading knowledge” — Hedberg, 1981; quoted in Greener, 2016

WHY UNLEARNING IS IMPORTANT

Unlearning is required to facilitate new learning

- unlearning is often viewed as a step that occurs before learning can occur

- in a rapidly changing field like medicine, there is continual dynamic interplay between learning and unlearning

- understanding unlearning allows us to understand our own behaviour at an individual and organisational level

- Unlearning is a skill in itself, and necessary for future learning and adaptive change

- We need to be careful about what we unlearn (e.g. Will new evidence be upheld by subsequent studies? Are we changing the right things following a ‘sentinel event’?)

Medicine is a complex rapidly changing field with an evolving scientific basis. ‘Medical reversal’ is common:

- Medical reversal is the phenomenon of a new superior trial arising that contradicts current clinical practice

- Prasad et al (2013) found that out of the 2004 ‘Original Articles’ published in the New England Journal of Medicine from 2001 to 2010, 363 articles tested an established therapy. Of these 146 (40.2%) reversed that practice, whereas 138 (38.0%) reaffirmed it.

- Clinicians often have greater difficulty unlearning outmoded practices than they do in adopting new ones (Ubel and Asch, 2015)

Despite this, in medicine, we can be slow to ‘unlearn’ and change practice

- On average, it takes 17 years for scientific evidence from randomised clinical trials to be implemented into routine care (Morris et al, 2011)

- Niven et al (2015):

- in an 11 year study of ICUs in the USA, ‘tight glycaemic control’ was increasingly adopted – albeit slowly —following the Leuven 1 trial (published in NEJM in 2001) at a rate of 1.7% of patients per quarter (absolute increase of only 5% in approximately 7 years)

- However, this trial was superseded by the definitive NICE-SUGAR trial (published in NEJM in 2009), which showed that ‘tight glycaemic control’ causes harm

- Despite this there was no decrease in the proportion of ICU patients with ‘tight glycaemic control’ in ICUs in the USA

- Rates of adoption following ‘positive’ trials, and de-adoption following ‘negative’ trials, varies considerably by intervention and by specialty (Niven et al, 2015). Rates appear to be slower in critical care than in cardiology, for instance. The reasons for this are likely to be multifactorial.

- New diagnostic tests tend not to replace ‘old’ tests, but become investigations used in addition by clinicians (Eisenberg et al, 1989)

- Adoption and de-adoption are not symmetrical processes (see below)

Health professionals are knowledge workers who are delivered an ever-expanding flow of information, and due to the rapidity of change, are at risk of ‘reform fatigue’ (apathy to, and tiredness from, recurrent reform). (Rushmer and Davies, 2004)

- Protocols embedded at an organisational level can “fossilise”, impeding innovative practice change

High rates of medical error and the current patient safety crisis in healthcare means it is both clinically relevant and politically astute to better understand unlearning

TYPES OF UNLEARNING

There are 3 types of unlearning (Rushmer and Davies, 2004; Coombs et al, 2013):

- Routine Unlearning (“Fading”)

- Directed Unlearning (“Wiping”)

- Deep Unlearning

Routine Unlearning (“fading”)

Some forms of learning, such as simple behavioural habits, passively fade over time when the factors sustaining learning are removed (e.g. repetition, retrieval, reinforcement, application or assessment)

Fading is ‘forgetting’, and the rate can be described using Ebbinghaus’ ‘forgetting curve’

Characteristics

- occurs through lack of use

- has minor impact on the individual

- occurs slowly

- minimal emotional impact and is usually subconscious

Example

- Changing how blood tests are ordered on a computerised ordering form, will initially lead to delays and difficulties in completing the form

- However, through repeat exposure practitioners naturally forget old habits (e.g. where the box for “lipase” used to be) and learn the new format

Directed Unlearning (“wiping”)

Requires conscious deliberate active actions by an individual to change the why they think and act

Characteristics

- usually triggered by an imposed change event

- typically targets a change in individual behaviour, but may involve abandoning knowledge

- occurs at variable speed, but usually isn’t sudden

- emotional impact is variable, but not usually significant

Examples

- forcing strategies (e.g. preventing alternative actions)

- persuasion (e.g. education about new evidence)

Deep unlearning

Deep unlearning occurs when one’s mental model is proven to be incorrect, revealing a gap between reality and what we believed about the world

Characteristics

- usually triggered by an unexpected (usually unpleasant) individual experience

- typically leads to questioning of values and/or identity, not just changing knowledge or behaviour

- usually sudden

- the emotional impact is usually significant and challenging

Example

Involvement in a tragic event at work resulting in strong emotional responses and cognitive dissonance, which leads to rapid transformation in beliefs about competency and how to perform procedures

WHY UNLEARNING CAN BE DIFFICULT

Unlearning can be difficult at both the level of the:

- Individual

- Organization

Unlearning is difficult for individuals due to:

- Discomfort (Rushmer and Davies, 2004)

- People usually need to lose faith in pre-existing mental models in order to develop new ones (see Cognitive Rigidity)

- Habit and feelings of security in one’s ‘comfort zone’

- Fear of the unknown

- Pre-existing cognitive tools and mental shortcuts may be well established (e.g. stereotypes, mental models and mindsets) and unlearning leads to initial disorientation and loss of self-efficacy

- Lack of awareness, either through lack of feedback, confirmation bias or ‘ego/ cognitive defence’ (see below)

- Unlearning can be painful, may lead to harmful emotions and lead to a grieving cycle

- Cognitive biases affect how we interpret new information (Ubel and Asche, 2015), important examples include:

- confirmation bias — tendency to favour information that confirms prior beliefs

- availability bias — judgement is influenced by the information that comes most easily to mind

- specialty bias — a propensity to recall rare and unusual cases

- endowment effect — we tend to value things that we own more, such that taking something is experienced as a disproportionately large loss

- false attribution of causation — we have a tendency to attribute causality to individual cases even thought the benefits, or absence thereof, are only visible at an aggregate level

- Desire to reduce cognitive dissonance easier to live with actions or a decision if engage in self-deception and (falsely) believe that evidence does not apply

- Increased experience and expertise (Klein, 2011)

- these individuals tend to have more sophistical mental models and a greater capacity to ‘explain away’ anomalies

- Thus it can be more difficult for experts to learn that it is for novices

- In general, experts have to put in more effort to disconfirm their mental models than do novices

- However, one of the reasons a true expert has developed expertise might be that she is more skilled at unlearning!

Unlearning is difficult for organisations, according to Rushmer and Davies (2004), due to:

- Stability, predictability and certainty are valued characteristics of organisations

- useful when dealing with routine tasks

- lead to inertia that prevents adaptation in times of change

- Organisations have a ‘dominant logic’ that acts analogous to an individual’s cognitive defence to prevent change

- the ‘dominant logic’ is the prevailing culture resulting from collective preconceptions about what the organisations is about, its institutional history and its environment

- group norms and role expectations may prevent individual unlearning from transmitting to the organisation

- The inability to question successful organisational norms, values and practices can become a ‘competency trap’, in which outdated competencies can never be abandoned

- Power gradients

- it may be difficult to challenge senior individuals and appointed leaders who have outdated practices

- Tendency to narrow the focus of change

- this is rarely successful as their areas of change must still interact with and conform to those that remain fossilised in old ways

- Centralised decision-making

- decision makers may be out-of-touch with front-line decision makers

- information gets filtered as it passes up the chain (and is often cast in a favourable light)

- Resource allocation, promotion, decision-making authority

- may lead others who stand to lose out to sabotage attempts to unlearn

- may include bodies external to the organisation

- Fee-for-service reimbursement systems

- other interests may compete with optimal patient care

WHY DE-ADOPTION IS NOT SIMPLY THE REVERSE OF ADOPTION

The processes of adoption and de-adoption are asymmetrical – they are not simply the reverse of one another (Ubel and Asche, 2015).

Reasons for this include:

- Different stakeholders are involved

- Psychologically, gains and losses are not perceived symmetrically

- Healthcare organisations typically place an emphasis on increasing high-value care, rather than decreasing low-value care

- Market-oriented health care systems are less likely to discontinue to provide financially rewarded services

- e.g. cancer screening that leads to more biopsies

- Clinicians have a tendency to want to collect more information (data) even if not shown to improve outcomes

- e.g. invasive monitoring in ICU

- e.g. laboratory sleep tests for sleep disorders when patients are likely to have obstructive sleep apnoea

- Adopters risk “losing face” or having to admit they have been causing harm by stopping an outmoded practice

- Different clinicians/ specialities may have disagreements over the evidence base (e.g. cancer screening, stroke thrombolysis) due to preconceptions (e.g. confirmation bias)

QUALITIES THAT PROMOTE UNLEARNING

The individual qualities overlap considerably with qualities associated with learning (Rushmer and Davies, 2004):

- Openness to vulnerability (e.g. able to accept that one is wrong)

- Willingness to listen and consider new ideas (e.g. from more junior or even disliked colleagues)

- Capacity to explore feelings and reflect and act in new ways (e.g. to work through the grieving cycle and foster positive change)

- Tolerance for feeling inadequate, embarrassed or humiliated

- Acceptance of potential loss of status or credibility

- Bravery and willingness to accept personal risk

However, organisational qualities are also important (Rushmer and Davies, 2004):

- Social environment that supports openness, creativity, and vulnerability

- Trust between individuals

- Individuals that appreciate one another and demonstrate regard for one another’s expertise and experience

- Interprofessional groups able to talk to one another

EXPERIENCE OF UNLEARNING BY CLINICIANS

Gupta et al (2017) used a grounded theory-based approach in a qualitative study. They studied the physician experience of unlearning an outmoded clinical practice in relation to learning a new one. Consistent themes from the 17 academic general physicians interviewed were:

- “Practice change disturbs the status quo equilibrium and that establishing a new equilibrium that incorporates the change may be a struggle” (Gupta et al, 2017)

- The struggle is greater if the change involves stopping a practice rather than adding a new one

- The discomfort may result from the individual experience of change or from difficulties in implementation

- Guideline changes introduce a feeling of uncertainty and may lead to practice variation between early and late (de-)adopters

- Patients may also provide resistance to change, as they may be inconvenienced or be invested in previous practice, and many clinicians alter their practice to respect patient autonomy

- Struggle includes the “evidence” itself and tensions between evidence and context (Gupta et al, 2017)

- Quality of evidence is reported as an important factor that physicians will use to support their unlearning

- In the absence of high quality evidence, local data and discussion with colleagues is used

- Physicians use guidelines “to guide” not “to dictate” practice and rely on discussion with colleagues in order to determine the external validity of the evidence and to implement the guideline

- this interpretation is susceptible to the usual biases and preconceptions (see above)

- The struggle to change is dynamic, often with a phase of trial-and-error and contingency plans with the outmoded practice rarely completely unlearned

TECHNIQUES TO PROMOTE UNLEARNING

Individual level

- Raise awareness of the unlearning process and the necessity of failure for improvement and eventual success

- Education and persuasion

- about the evidence base for the change

- the impact on patient outcomes of new practices (or the absence with old practices)

- how to implement

- Awareness of psychological biases

- may help better interpretation of evidence and evidence-based guidelines

- Use specific education strategies

- use strategies that prevent or restrict application of pre-existing mental models to learning tasks

- e.g. do not allow the keyboard to be visible when learning touch typing

- Use experts in practice to “think aloud” their reasoning and identification of the cues they are paying attention to so that others can learn from them

- Simulation-based learning

- e.g. harness the impact of “deep unlearning” in a psychologically safe environment that does not put patients at risk

- use strategies that prevent or restrict application of pre-existing mental models to learning tasks

- Use strategies to guard against cognitive rigidity and promote unlearning (see Cognitive Rigidity)

- Social media

- highlighted by Greener (2016) has having potential for facilitating deep unlearning through its “ubiquity, intimacy, and sheer speed”

Organizational level

- Foster a ‘no blame’ culture of mutual respect and communication between inter-professional groups

- Effective leadership that understands change management and the need to be adaptive

- Use forcing strategies where directed unlearning is appropriate

- e.g. electronic prescribing that prevents harmful drug interactions

- Provide support for individuals undergoing deep unlearning

- Guideline and protocol committees should have a range of experts so that their preconceptions and biases balance one another out (Ubel and Asche, 2015)

Different responses are appropriate when unlearning is triggered by an individual learning episode compared to an organizational change event.

References and Links

FOAM and web resources

- Mind, Improvement, and Medical Education (MIME) LITFL

- The Backwards Brain Bicycle – Smarter Every Day 133

- Learning Deeply — Unlearning Is Critical for Deep Learning (2015)

- HBR — Why the Problem with Learning Is Unlearning (2016)

- Wiesbauer F. Teaching Masterclass: The Psychology of Learning. Medmastery

Journal articles and books

- Coombs C, Hislop D, Holland J, Bosley S, Manful E. Exploring types of individual unlearning by local health-care managers: an original empirical approach. Health Services and Delivery Research. 1(2):1-126. 2013.

- Gupta DM, Boland RJ, Aron DC. The physician’s experience of changing clinical practice: a struggle to unlearn. Implementation science : IS. 12(1):28. 2017. [PMC5331724]

- Hislop D, Bosley S, Coombs CR, Holland J. The process of individual unlearning: A neglected topic in an under-researched field. Management Learning. 45(5):540-560. 2013.

- Klein, GA. Streetlights and Shadows: Searching for the Keys to Adaptive Decision Making. MIT Press, 2011

- Morris ZS, Wooding S, Grant J. The answer is 17 years, what is the question: understanding time lags in translational research. J R Soc Med. 2011;104: 510–20. [PMC3241518]

- Niven DJ, Rubenfeld GD, Kramer AA, Stelfox HT. Effect of published scientific evidence on glycemic control in adult intensive care units. JAMA internal medicine. 175(5):801-9. 2015. [PMID 25775163]

- Rushmer R, Davies HT. Unlearning in health care. Quality & safety in health care. 13 Suppl 2:ii10-5. 2004. [PMC1765805]

- Tsang EW, Zahra SA. Organizational unlearning. Human Relations. 61(10):1435-1462. 2008.

- Solovy A. The unlearning curve: learning is only half the process of achieving organisational change. Hosp Health Netw 1999;73:30. [PMID 10067157]

- Ubel PA, Asch DA. Creating value in health by understanding and overcoming resistance to de-innovation. Health affairs. 34(2):239-44. 2015. [PMID 25646103]

Chris is an Intensivist and ECMO specialist at The Alfred ICU, where he is Deputy Director (Education). He is a Clinical Adjunct Associate Professor at Monash University, the Lead for the Clinician Educator Incubator programme, and a CICM First Part Examiner.

He is an internationally recognised Clinician Educator with a passion for helping clinicians learn and for improving the clinical performance of individuals and collectives. He was one of the founders of the FOAM movement (Free Open-Access Medical education) has been recognised for his contributions to education with awards from ANZICS, ANZAHPE, and ACEM.

His one great achievement is being the father of three amazing children.

On Bluesky, he is @precordialthump.bsky.social and on the site that Elon has screwed up, he is @precordialthump.

| INTENSIVE | RAGE | Resuscitology | SMACC

You’ve certainly mounted an argument for ‘unlearning’ as a scholarly notion. I’ve always thought unlearning wasn’t really a ‘thing’ preferring instead to frame this so called unlearning simply as a form of learning. Maybe that’s what I’m doing right now. Thanks for the provocation.

Thanks Debra

Undoubtedly learning and unlearning are two sides of the same coin.

Unlearning seems to be the harder part in some circumstances though – perhaps analogous to Kuhn’s conception of scientific progress: being either incremental within a paradigm or a major shift when a paradigm is replaced.

Thanks for reading!

Chris

Unlearning is forgetting, discarding and removing from priority list. My three books on #unlearning can be referred. Unlearn Before You Learn what I say, #UnlearnBeforeULearn