Acute Aortic Dissection

OVERVIEW

- the most common catastrophe of the aorta (3:100,000); 3 times more common than abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) rupture

- aortic dissection is a type of acute aortic syndrome (AAS) characterized by blood entering the medial layer of the wall with the creation of a false lumen.

- AAS is a spectrum of life-threatening thoracic aortic pathologies including intramural haematoma, penetrating atherosclerotic ulcer, and aortic dissection.

CLASSIFICATION

Stanford (most commonly used)

- Type A — Involves ascending aorta. Can extend distally ad infinitum. Surgery usually indicated.

- Type B — Involves aorta beyond left subclavian artery only. Often managed medically with BP control.

DeBakey

- entire aorta affected

- confined to the ascending aorta

- descending aorta affected distal to subclavian artery

Svensson (defines type of acute aortic syndrome)

- classic dissection with true and false lumen

- intramural haematoma or haemorrhage

- subtle dissection without haematoma

- atherosclerotic penetrating ulcer

- iatrogenic or traumatic dissection

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

There are 3 possibilities as to how the blood enters the media:

- Atherosclerotic ulcer leading to intimal tear

- Disruption of vasa vasorum causing intramural haematoma

- De novo intimal tear

Following dissection, blood flow into the media may cause:

- extension up or down

- rupture

- vessel branch occlusion

- aortic regurgitation

- pericardial effusion / tamponade

HISTORY

Chest pain is classically ripping or tearing in nature, that occurs suddenly and is maximal at onset – however, chest pain is not always present!

- retrosternal chest pain – anterior dissection

- interscapular pain – descending aorta

- severe pain (‘worst ever-pain’) (90%)

- sudden onset (90%)

- sharp (64%) or tearing (50%)

- migrating pain (16%)

- down the back (46%)

- maximal at onset (not crescendo build up, as in an AMI)

Other features

- end-organ symptoms: neurological, syncope, seizure, limb paraesthesias, pain or weakness, flank pain, SOB + haemoptysis

- aortic regurgitation

- hypertension

- most have ischaemic heart disease

Atypical presentations are common

- consider the diagnosis of acute aortic dissection if there is a combination of chest/ back pain and new or evolving neurological deficit(s)

RISK FACTORS

Inherited disease (especially younger patients < 40 yrs)

- Marfan’s syndrome (fibrillin gene mutations)

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV (collagen defects)

- Turner syndrome

- annulo- aortic ectasia

- familial aortic dissection

Aortic wall stress

- Hypertension (72% (and other CV risk factors: smoker, lipids))

- previous cardiovascular surgery

- structural abnormalities (e.g. bicuspid or unicommisural aortic valve, aortic coarctation)

- iatrogenic (e.g. recent cardiac catheterisation)

- infection (syphilis)

- arteritis such as Takayasu’s or giant cell

- aortic dilatation / aneurysm

- wall thinning

- ‘crack’ cocaine (abrupt catecholamine-induced hypertension)

Reduced resistance aortic wall

- Increasing age

- pregnancy (debatable)

EXAMINATION

Features include:

- aortic regurgitation is common

- hypertension (if hypotensive ensure it is not due to limb discrepancy caused by an occluded vessel – check BP in the arm with best radial pulse)

- shock – ominous signs: tamponade, hypovolaemia, vagal tone

- heart failure

- neurological deficits: limb weakness, paraesthesiae, Horners syndrome

- SVC syndrome – compression of SVC by aorta

- asymmetrical pulses (carotid, brachial, femoral)

- haemothorax

COMPLICATIONS

Suspect if hypotensive (check for limb discrepancy!)

- aortic rupture

- aortic regurgitation

- acute myocardial infarction

- cardiac tamponade

- end-organ ischaemia (brain, limbs, spine, renal, gut, liver)

- death

INVESTIGATIONS

Bedside

- ECG

- normal

- inferior ST elevation (right coronary dissection) but can be any STEMI (0.1% of STEMIs are dissections)

- pericarditis changes, electrical alternans (tamponade)

Laboratory

- leukocytosis

- Cr elevation with renal artery involvement

- tropnonin elevated if dissection causes myocardial ischaemia

- D-dimer – if negative dissection is very unlikely, but not sufficient to rule out

- Cross-match

- Various biomarkers being investigated (e.g. elastin fragments, d-dimer, smooth muscle myosin heavy-chain protein)

Imaging

- CXR

- Widened mediastinum (56-63%), abnormal aortic contour (48%), aortic knuckle double calcium sign >5mm (14%), pleural effusion (L>R), tracheal shift, left apical cap, deviated NGT. ‘Normal’ in 11-16%.

- Echocardiography

- Transthoracic

- 75% diagnostic Type A (ascending), 40% descending (Type B)

- can identify complications (e.g. aortic regurgitation, regional wall abnormalities in cardiac ischaemia, cardiac tamponade)

- Transoesophageal (TOE)

- Much higher sensitivity/specificity, though operator-dependent, need sedation, and is less available

- Useful in ICU / perioperative

- Upper ascending aorta and arch not well visualised

- Transthoracic

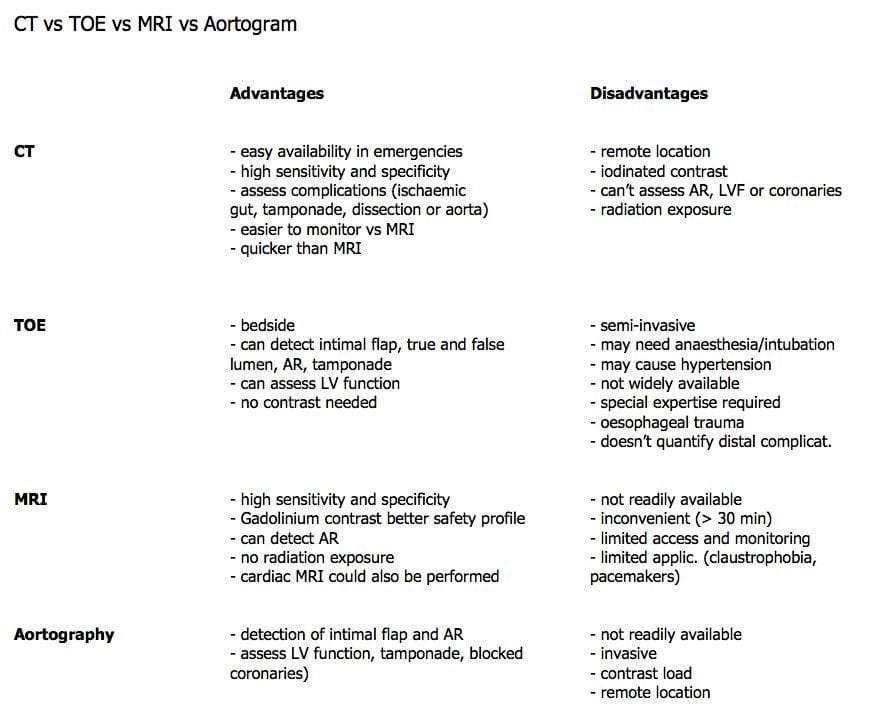

- Helical CT

- Useful screen for widened mediastinum. Newer multiplane/slice scanners may now negate additional need for TOE or aortography to plan operative management.

- Aortography – Was the traditional gold standard, delineating aortic incompetence and associated branch vessel involvement as well.

- MRI / MRA – Excellent sensitivity and specificity limited by availability.

MANAGEMENT

Emergent priorities

- control BP

- control bleeding

- fluid resuscitation

- O2

- wide bore IV access (Swan sheath)

- invasive monitoring

- warn blood bank (x-match 6U + need for other products)

- correct coagulopathy

- control HR and BP (aim for P 60-80 and BP 100-120 SBP)

- IV beta blocker (propranolol, esmolol or labetalol) combined with vasodilators (e.g. GTN, labetalol, SNP)

- start b-blocker first to avoid increased aortic wall stress from reflex tachycardia

- call cardiothoracic surgeon

Indications for surgery

- Persistent pain

- Type A

- Branch Occlusion

- Leak

- Continued extension despite optimal medical management

Intra-operative management

- avoid hypertension on induction

- fast, full and forward

- dissection and clamps may interfere with arterial monitoring

- TXA2

- femoral arterial cannulation used for bypass

- anticoagulate before bypass

- if aortic root involved then patient may need AVR with coronary artery reimplantation

- monitor BP after bypass closely

- may have dissected into other organs (monitor function)

Circulatory Arrest

- deep hypothermic arrest (DHA) required during arch surgery as it isn’t possible to perfuse cerebral vessels on bypass

- safe duration = 45min @ 18 C

- other ways of protecting brain; pack head with ice, thiopentone, methylprednisonlone mannitol, GTN (to prevent vasoconstriction)

- POCD proportional to DHA time

- once circulation arrested -> all infusion and pumps stopped

- when warming do not set FAW to >10 C (prevents burns), start propofol and fix coagulopathy with products

Standard post-operative care

References and Links

LITFL

- CT scan 006 – Aortic dissection

- Cardiovascular Curveball 008 — DeBakey’s Dissection

- Trauma Tribulation 034 — Trauma Under Pressure

Journal articles and textbooks

- Diercks DB et al. Clinical Policy: Critical Issues in the Evaluation and Management of Adult Patients With Suspected Acute Nontraumatic Thoracic Aortic Dissection. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 65(1):32–42.e12. PMID 25529153

- Golledge J, Eagle KA. Acute aortic dissection. Lancet. 2008 Jul 5;372(9632):55-66. Review. PubMed PMID: 18603160.

- Holloway BJ, Rosewarne D, Jones RG. Imaging of thoracic aortic disease. Br J Radiol. 2011 Dec;84 Spec No 3:S338-54. doi: 10.1259/bjr/30655825. Review. PubMed PMID: 22723539; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3473913.

- Lentini S, Perrotta S. Aortic dissection with concomitant acute myocardial infarction: From diagnosis to management. J Emerg Trauma Shock [serial online] 2011 [cited 2013 Apr 21];4:273-8. Available from: http://www.onlinejets.org/text.asp?2011/4/2/273/82221

- Upadhye S, Schiff K. Acute aortic dissection in the emergency department: diagnostic challenges and evidence-based management. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2012 May;30(2):307-27, viii. Review. PubMed PMID: 22487109.

FOAM and web resources

- ALIEM — Paucis Verbis: International Registry on Aortic Dissection (IRAD)

- International registry of Acute Aortic Dissection

- EMCrit Podcast 91 – Treatment of Aortic Dissection

- EMLON — How Do We Miss Aortic Dissection?

- EM Updates — ACC/AHA Aortic Dissection Guideline

- NNT — Aortic dissection

- Radiopaedia — Aortic dissection

Critical Care

Compendium

Chris is an Intensivist and ECMO specialist at The Alfred ICU, where he is Deputy Director (Education). He is a Clinical Adjunct Associate Professor at Monash University, the Lead for the Clinician Educator Incubator programme, and a CICM First Part Examiner.

He is an internationally recognised Clinician Educator with a passion for helping clinicians learn and for improving the clinical performance of individuals and collectives. He was one of the founders of the FOAM movement (Free Open-Access Medical education) has been recognised for his contributions to education with awards from ANZICS, ANZAHPE, and ACEM.

His one great achievement is being the father of three amazing children.

On Bluesky, he is @precordialthump.bsky.social and on the site that Elon has screwed up, he is @precordialthump.

| INTENSIVE | RAGE | Resuscitology | SMACC