CT Case 027

An 84-year-old male presents with sudden severe central abdominal pain, onset 12 hours prior to presentation.

His pain had eased from 9/10 to 3/10 on arrival with associated nausea, vomiting, and diarrhoea.

His previous history includes atrial fibrillation, T2DM and dyslipidaemia. He is not anticoagulated. (CHA₂DS₂-VASc score = 3, mod-high risk).

Admission bloods reveal a lactate of 4.9.

Describe and interpret the CT images

CT INTERPRETATION

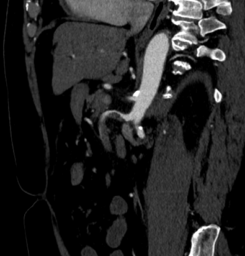

This is a CT mesenteric angiogram ischaemic protocol (arterial and portal venous phase).

There is a filling defect in the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), consistent with thrombus.

Thrombus may be embolic from the heart or form in-situ secondary to a dissection.

There is still some distal opacification as the thrombus is not completely occlusive and there is probably collateral supply via the inferior mesenteric artery.

The small and large bowel are normal diameter.

No pneumatosis coli or intestinalis. No portal venous gas.

No free fluid.

CLINICAL CORRELATION

This elderly gentleman, with atrial fibrillation and multiple vascular risk factors is at very high risk for embolic events.

The SMA is the most commonly affected vessel in mesenteric thrombo-embolisation. This is likely due to its narrow angle of take-off from the aorta. It supples the pancreas, portions of the duodenum, the jejunum, ileum, ascending colon, and transverse colon, so it is these areas that we need to look at particularly for signs of gut ischaemia.

CT mesenteric angiogram ischaemic protocol has both an arterial and portal venous phase.

The arterial phase is of course to look for the arterial occlusion.

The portal venous phase is important in assessing the bowel for signs of ischaemia (as well as assessing for venous occlusion). Luckily, this this patient had no established signs of bowel infarction on his CT.

Bowel ischemia can have a myriad of imaging appearances, depending on the stage of ischemia at the time of the study.

The signs we look for include;

- Bowel wall thickening – this is from mucosal oedema and haemorrhage

- Bowel wall dilation – ischaemia disrupts the peristaltic ability of the bowel

- Bowel wall hypoenhancement – due to reduced or no flow to the bowel wall

- Bowel wall hyperenhancement – if perfusion is restored, bowel wall hyperaemia will follow, causing mural hyperenhancement

- Gas in the bowel wall or portal vein – Seen in end-stage ischaemic, when there is not just ischaemia, but when infarction has occurred

This patient was managed with heparin infusion and urgent transfer to theatre for embolectomy.

References

- Hartung MP. Abdominal CT: intestinal ischaemia. Medmastery

- CHA₂DS₂-VASc Score for Atrial Fibrillation Stroke Risk. MDCalc

[cite]

TOP 100 CT SERIES

Sydney-based Emergency Physician (MBBS, FACEM) working at Liverpool Hospital. Passionate about education, trainees and travel. Special interests include radiology, orthopaedics and trauma. Creator of the Sydney Emergency XRay interpretation day (SEXI).

Provisional fellow in emergency radiology, Liverpool hospital, Sydney. Other areas of interest include paediatric and cardiac imaging.

Emergency Medicine Education Fellow at Liverpool Hospital NSW. MBBS (Hons) Monash University. Interests in indigenous health and medical education. When not in the emergency department, can most likely be found running up some mountain training for the next ultramarathon.

Dr Leon Lam FRANZCR MBBS BSci(Med). Clinical Radiologist and Senior Staff Specialist at Liverpool Hospital, Sydney

Hi is there left kidney cortical wedge shape infarct as well

Good thought, but on multiple slices it is obviously a renal cyst