Psychological Safety and Simulation

OVERVIEW

Psychological safety is the perception of the consequences of taking interpersonal risks in a given group context (Edmondson et al, 1999; Edmondson, 2018).

- High psychological safety is present when an individual feels they can speak their mind without fear of ridicule, embarrassment, or punishment and that there is mutual respect and trust among the team.

- At any given time different members of a group may experience different levels of psychological safety

Psychological safety is required for:

- effective team interactions (both in simulation and in the workplace)

- speaking up (which refers to a person in a non-dominant or non-leader role expressing a concern or suggested course of action to another person in a dominant or leader role)

- effective debriefing

Psychological safety in simulation and in the workplace have a bidirectional impact on one another (Purdy et al, 2022), highlighting the responsibility of both simulation facilitators and healthcare leaders to create, maintain, and regain psychological safety.

PRE-CONDITIONS FOR PSYCHOLOGICAL SAFETY

Pre-conditions for psychological safety relate to (Kolbe et al, 2019):

- Pre-brief

- Individual characteristics

- Team characteristics

- Organisational characteristics

Pre-brief (creating the “Safe Container” – Rudolf et al, 2014)

- Introductions (faculty and participants)

- Basic assumption: everyone is trying their best (treat with positive regard)

- Fiction contract (treat the simulation as though it were real)

- Confidentiality

- Not an assessment (focus on learning, not “success”)

- Normalise mistakes (“growth mindset”: mistakes are how we learn)

- Orientation to Objectives, Session plan, and simulation environment

Individual characteristics

- Proactive personality (engages regardless of external forces)

- Emotional stability (calm, relaxed, and stable)

- Learning orientation (focuses on learning new skills not high performance)

Team characteristics

- Inclusive leadership (invites and appreciates contributions of others)

- Peer support

- Trust

- Mutual respect

- Work design characteristics – role clarity, interdependence, and autonomy

Organisational characteristics

- Just culture (as opposed to a blame culture) and supportive work context

- High quality relationships

- Commitment-based human resources practices

Note if any of the pre-conditions are lacking, they may override any of the others (e.g. a well delivered brief may not offset a toxic workplace culture). Indeed, Purdy et al (2022) note that the “safe container” is a “leaky construct”. In other words, the pre-existing state of psychological safety of simulation participants impacts on their simulation experience, which in turn impacts on their experience in the real working environment. These impacts can be positive or negative.

ACTIONS THAT MAINTAIN PSYCHOLOGICAL SAFETY

Numerous actions can contribute to psychological safety during simulation (Kolbe et al, 2019).

- They include:

- Explicit strategies – verbal communication strategies

- Implicit strategies – attitudes and non-verbal behaviours

- They occur:

- Before debriefing

- During debriefing

- After debriefing

Explicit strategies (Kolbe et al, 2019):

| Before the debrief | During the debrief | After the debrief |

Clarify expectations Commit to confidentiality and transparency Commit to respectful behaviour Inclusive language Attend to logistics | Turn taking Validation and apology if concerns about realism expressed Open-ended questions (demonstrate curiosity) Show appreciation (“thanks for that”) Normalise by helping to understand why challenging Demonstrate vulnerability (e.g. through stories) Active listening and paraphrasing Verbal sign-posting Help learners by being directive when needed | Invite feedback to show genuine interest in improvement Offer and provide emotional support At end of debrief apologise if not enough time and arrange for follow up discussion |

Implicit strategies (Kolbe et al, 2019):

| Before debrief | During debrief | After debrief |

| Private and quiet environment Arrive early and start on time Arrange seats in a circular manner Ensure co-facilitators are across from one another (integrated and able to see all participants) | Be mindful of timing Demonstrate behavioural integrity (“walk the talk”) Convey empathy by mirroring Pause to listen after questions Use positive affect and eye contact Positive regard Use open ended questions (not GWITs – “guess what I am thinking” questions) Hold learner in positive regard (belief that learners are doing their best and want to learn) Avoid negative behaviours that convey: – Contempt (e.g. eye roll, sarcasm) – Belligerent (e.g. “do not interrupt me”) – Domination (e.g. patronising behaviour, invalidation) – Defensiveness (e.g. folded arms, “yes, but”) Do not complain about others not present | At end see participants off and give them time to leave Do not dispose of debrief notes while participants are present Respect confidentiality |

Purdy et al (2022) also suggest practical tips for managing the bidirectional flow of psychological safety into and out of simulation:

| Minding the leaks in | Shaping the leaks out |

|---|---|

| Diagnose and manage the team dynamics before even entering the room (e.g. prior experience with simulation, team familiarity, hierarchy, pre-existing relationships, and power dynamics) | Stop saying, “what happens in simulation, stays in simulation”. Simulation impacts ideas, relationships, and judgements participants have about colleagues, their organizations, and themselves. |

| Reflect on your own positioning as a facilitator. Your credibility and pre-existing relationships with participants matter. Ensure you foster psychological safety outside of the simulation room. | Continue employing traditional ways of building, maintaining, and repairing psychological safety in the simulated environment (e.g. the implicit and explicit strategies described above). This likely results in a significant leak of familiarity, confidence, leadership behaviours, and trust back into the working environment. |

| Commit at an organizational level to the an improvement ethos that simulation is a part of (not an isolated event). | Start overtly debriefing around concepts related to psychological safety. Name and explore ideas like familiarity, role understanding, supportive leadership, trust, inclusiveness, belonging, speaking up, and confidence—or what gets in the way of them. |

BREACHES OF PSYCHOLOGICAL SAFETY IN SIMULATION

Kolbe et al (2019) also describe strategies for managing breaches of psychological safety in simulation. When a breach in psychological safety occurs, individuals:

- Will not feel safe to take risks (such as speak up or attempt actions where they may fail)

- Engage in face saving behaviours (e.g. withdrawal from participation, reluctance to ask for help or disclose errors, and tendency to obscure critique)

- View ambiguous stimuli as threats

Suspect a breach in psychological safety during a debrief when participants:

- “go quiet” (especially if usually engaged and contributes to discussions)

- Become “defensive” or “hostile”

- Complain about realism of the simulation

- Avoid eye contact

- Start arguing or criticising others

Address a breach in psychological safety by:

- Recognise the breach

- Reframe the learner’s behaviour as a rational response to to their own perceptions

- Change your debriefing behaviour as a “first line treatment” (rather labelling the learner as a “difficult person”, etc)

- Respond with explicit and implicit reactions:

- Project a positive affect

- Validate and normalise the learner’s response

- Apologise

- Name the dynamic, where appropriate – i.e. draw conversation to the here and now and attend to patterns present in the moment; name and validate the pattern calmly and with positive regard

- Debrief the debrief afterward and arrange appropriate follow up (e.g. speak with and support distressed participants)

SIMULATION’S IMPACT ON PSYCHOLOGICAL SAFETY

Speaking up

- O’Donovan and McAuliffe (2020) performed a systematic review that included 5 studies of simulation to enable speaking up behaviour (an indirect marker of psychological safety). Findings were mixed, likely reflecting different contexts and how the simulation interventions were delivered. Findings included:

- simulation can, but not always, lead to improved speaking up behaviour in clinical teams

- early and negative evaluative statements about team or individual performance may hinder speaking up

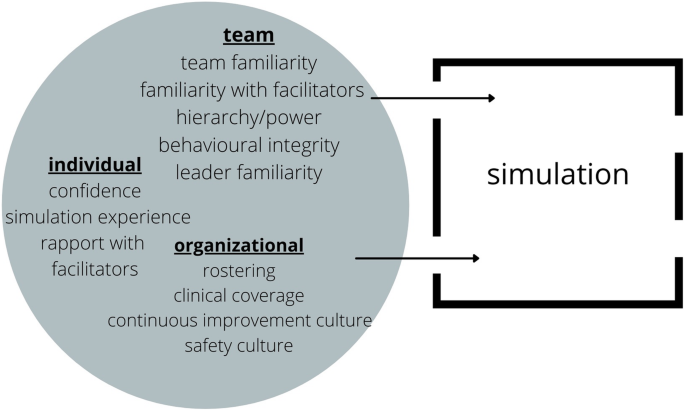

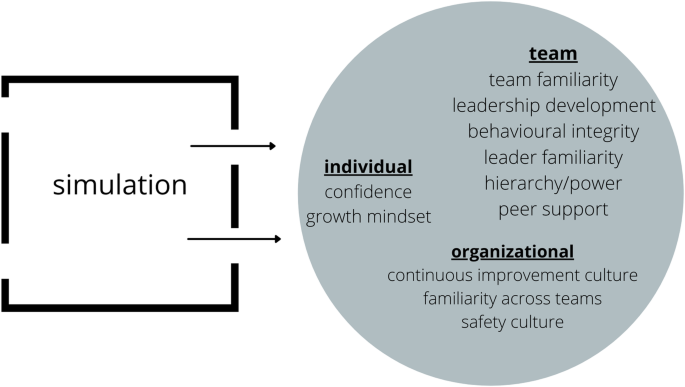

Bidirectional flow between simulation and the workplace

- Purdy et al (2022) performed a qualitative study of the bidirectional impact of psychological safety between simulation and the workplace. They found that these impacts can be positive or negative, and occur at the individual, team, and organizational levels. Examples included:

- prior individual simulation experience affects future simulation experience

- simulation experience affects confidence and experience in the workplace

- simulation can as as “an incubator of familiarity and acts as a magnifying glass on behavioural integrity” and is a place where relationships are forged (especially important for those in new roles) and credibility can be built or lost.

- rostering choices related to simulation participation can lead to tension and hierarchy among staff and may negatively impact workplace performance (e.g. if insufficiently staffed workplace during in situ simulation)

- interdepartmental simulation can increase understanding of each others roles and improves relationships

TIPS AND TRAPS

Based on advice from Jenny Rudolf (Debrief2Learn, 2017)

- Show psychological safety rather than claiming it (“walk the walk”, don’t just “talk the talk”)

- Psychological safety is in the eye of the beholder, what is safe for one person may not be for another

- Do not say “this is a safe learning environment” – it is OK to say they we are striving for or committed to creating a safe learning environment

- Top three strategies for debriefers to maintain psychological safey:

- Transparency – signpost where the conversation is going

- Vulnerability – empathise with the challenge faced by learners and share stories from your own experience in similar situations where you made mistakes

- Humour – telling humorosu stories that illustrates the facilitator’s “human-ness” in everyday language can be helpful (be careful with humour – avoid causing offense, being overly self-deprecating, or distracting from learning points)

Many of the principles of psychological safety for simulation debriefing also apply to clinical debriefing, which can be even more challenging because:

- Relates to actual, rather than simulated, clinical practice

- Greater time pressure

- Less controlled environment

REFERENCES AND LINKS

FOAM and web resources

- Debrief2Learn – Podcast 004: Building a safe container for learning (Jenny Rudolph and Adam Cheng, 2017)

- LITFL – Safe container rules, OK? (Chris Nickson, 2020)

- LITFL – High performing teams: secrets of success (SMACC talk by Chris Hicks, 2020)

- Simulcast – 8 – The Safe Container for Simulation (featuring Jenny Rudolph, 2019)

- TEDx talks – Building a psychologically safe workplace (Amy Edmondson, 2014)

Journal articles

- Edmondson A. Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1999; 44(2):350-383. [article]

- Edmondson, AC. The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth. Wiley, 2018. [Google books]

- Kolbe M, Eppich W, Rudolph J, et al. Managing psychological safety in debriefings: a dynamic balancing act. BMJ Stel 2020;6:164–171. [abstract]

- O’Donovan R, McAuliffe E. A systematic review exploring the content and outcomes of interventions to improve psychological safety, speaking up and voice behaviour. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):1–1. [article]

- Purdy E, Borchert L, El-Bitar A, Isaacson W, Bills L, Brazil V. Taking simulation out of its “safe container”-exploring the bidirectional impacts of psychological safety and simulation in an emergency department. Adv Simul (Lond). 2022;7(1):5. Published 2022 Feb 5. doi:10.1186/s41077-022-00201-8 [article]

- Rudolph JW, Raemer DB, Simon R. Establishing a safe container for learning in simulation: the role of the presimulation briefing. Simul Healthc. 2014;9(6):339-49. [pubmed]

SMILE 2

Better Healthcare

Chris is an Intensivist and ECMO specialist at The Alfred ICU, where he is Deputy Director (Education). He is a Clinical Adjunct Associate Professor at Monash University, the Lead for the Clinician Educator Incubator programme, and a CICM First Part Examiner.

He is an internationally recognised Clinician Educator with a passion for helping clinicians learn and for improving the clinical performance of individuals and collectives. He was one of the founders of the FOAM movement (Free Open-Access Medical education) has been recognised for his contributions to education with awards from ANZICS, ANZAHPE, and ACEM.

His one great achievement is being the father of three amazing children.

On Bluesky, he is @precordialthump.bsky.social and on the site that Elon has screwed up, he is @precordialthump.

| INTENSIVE | RAGE | Resuscitology | SMACC