Trauma! Pelvic Fractures II

aka Trauma Tribulation 028

The trauma team’s initial assessment in Trauma Tribulation 027 has confirmed that your patient’s major injury is a fractured pelvis.

You decide that early stabilization of the pelvis is critical.

Questions

Q1. What are the objectives of pelvic stabilization?

Answer and interpretation

Reduction of pathological pelvic motion is probably most important clinically.

There are 4 main objectives:

- Prevent reinjury from pelvic motion

- Decrease pelvic volume

- Tamponade bleeding pelvic bones and vessels

- Decrease pain

Of note:

- Cadaver studies suggest that pelvic stabilisation methods does not generate sufficient pressures to tamponade bleeding.

- the increase in pelvic volume with widely diastased open book fractures is actually relatively small.

- disruption of the retroperitoneum leads to a non-compressible space for hemorrhage to accumulate.

Q2. How can pelvic fractures be stabilized?

Answer and interpretation

In the trauma bay, simple pelvic binders are all you really need!

Methods include:

- Pelvic binder (e.g. sheet, SAM sling, T-POD, etc)

- Anterior external fixation

- C clamp

- Pneumatic Anti-Shock Garment (PASG) aka Military Anti-Shock Trousers (MAST) — essentially obsolete

Pelvic binders

- If a pelvic binding device is not available a sheet can be wrapped around the patient’s pelvis, centered on the patient’s greater trochanters. The sheet can be secured by twisting the encircling ends around one another before being tied or clamped. Taping the thighs or the feet together also helps maintain the anatomical position of the pelvis.

- There is little evidence than one form of pelvic binding is better than any other. Some proprietary pelvic binders may allow better access to the pelvis for surgery or angiography.

- Pelvic binding may exacerbate injury in iliac wing (LC) fractures and injuries with an over-riding pubic symphysis. The goal should be to approximate normal anatomic alignment.

The recent EAST guidelines made the following evidence-based recommendations regarding pelvic binders:

- they reduce fractures, provide definitive stabilization and decrease pelvic volume

- they limit hemorrhage

- They work as well or better than external fixation in controlling hemorrhage

If possible, avoid rolling the patient and perform straight lifts. also, longitudinal traction on the affected side may benefit patients with acetabular fractures.

Learn more:

- Resus.ME — Pelvic splint improves shock

- Trauma.org — The Ideal Pelvic Binder

- Trauma Professional’s Blog — Compression Of The Fractured Pelvis With A Sheet

Having stabilised the pelvis you remain rightly concerned about the potential for life-threatening hemorrhage.

Q3. What is the source of haemorrhage in a major trauma patient with pelvic fractures?

Answer and interpretation

There are 4 potential sources:

- Surfaces of fractured bones

- Pelvic venous plexus

- Pelvic arterial injury

- Extra-pelvic sources (present in 30% of pelvic fractures — remember the SCALPeR mnemonic for sources of bleeding in trauma… see Q2 of Trauma! Major haemorrhage)

Classically venous hemorrhage is said to account for 90% of bleeding from pelvic fractures, and arterial only 10%. However arterial bleeding is more common than this in patients that have ongoing hemorrhage (e.g. despite pelvic binding or mechanical stabilisation) or have hemodynamic compromise.

Q4. How much blood loss can occur from a pelvic fracture?

Answer and interpretation

Suzuki et al (2008) point out that:

Haemorrhage from pelvic fracture is essentially bleeding into a free space, potentially capable of accommodating the patient’s entire blood volume without gaining sufficient pressure-dependent tamponade.

But why should bleeding from a pelvic fracture be considered bleeding into a free space?

- although true pelvic volume is about 1.5L this is increased with disruption of the pelvic ring

- the tamponade effect of the pelvic ring is lost in severe pelvic fractures with disruption of the parapelvic fascia

- pelvic fractures cause bleeding into the retroperitonal space, even when intact the retroperitoneal space can accumulate 5L of fluid with a pressure rise of only 30 mmHg

- hemorrhage can escape into the peritoneum and thighs with disruption of the pelvic floor (e.g. open book fractures)

Hemodynamically unstable open pelvic fractures have mortality rates as high as 70%!

Q5. What features suggest underlying arterial hemorrhage in patient’s with pelvic trauma?

Answer and interpretation

Michael McGonigal from The Trauma Professional’s blog suggests asking 6 questions to determine if arterial hemorrhage is likely:

- What type of mechanism caused the fracture?

— Anterior-posterior compression and vertical shear are the most common. - Are the vital signs stable?

— If not, rule out the other four likely sources first (chest, abdomen, multiple extremity fractures, external). Then blame the pelvis. - Is the fracture open? Arterial bleeding is very likely.

- How old is the patient?

— Elderly patients are more likely to have arterial bleeding, especially from gluteal artery branches. - What part of the pelvis is broken?

— If major sacral fractures or SI joint disruption (gluteal artery) or separation of the symphysis (pudendal artery) is present, think arterial bleeding. - Are there CT abnormalities?

— A vascular blush or large hematoma indicates significant bleeding.

In addition to the patient’s fractured pelvis, you’re concerned about possible co-existent abdominal injury.

Q6. What is your decision making approach to the patient with a combination of suspected abdominal and pelvic injuries?

Answer and interpretation

If the patient is hemodynamically stable

- apply a pelvic binder

- perform an abdominopelvic CT with IV contrast +/- CT cystography to identify abdominal and pelvic injuries and allow prioritisation of management. A pelvic ‘blush’ indicates the need for angiography and selective embolisation of the actively bleeding artery.

If the patient is haemodynamically unstable, then

- Commence hemostatic resuscitation

- Apply pelvic binder

- Perform bedside tests:

— AP pelvis XR — if normal, rules out pelvic fracture as cause of hemodynamic instability

— EFAST — check for hemo/pneumothorax and intra-abdominal free fluid.

— If EFAST is negative, confirm absence of intraperitoneal blood using supra-umbilical DPA - If pelvic fracture and:

— positive EFAST, or

— EFAST negative but DPA* positive

then the patient requires emergency laparotomy, during which pelvic stabilization and/or pre-peritoneal pelvic packing is performed pending definitive management of the pelvic injury - If the EFAST and DPA are negative, then the patient is treated as described in Q7 below.

- The patient may have an abdominopelvic CT with IV contrast +/- CT cystography once stabilized.

*DPA = diagnostic peritoneal aspirate performed by a supra-umbilical open approach

There is controversy over the sensitivity of the FAST scan in ruling out intraperitoneal hemorrhage, and whether DPA is necessary if FAST scan is negative in the context of coexistent pelvic trauma. This is discussed in the recent LITFL post: Weingart on Pelvic Trauma.

An experienced ultrasounographer performs a bedside FAST scan and there is no evidence of hemoperitoneum. No other significant injuries have been identified. Unfortunately the patient’s blood pressure plummets. She has weak peripheral pulses and her hands and feet are scarily cold…

Q7. What should be the destination of a hemodynamically unstable patient with isolated pelvic trauma and what is your approach?

Answer and interpretation

Not the CT scanner!

The approach to the hemodynamically unstable patient with isolated pelvic trauma is controversial, and varies between centers according to available resources and local protocols.

The main goal is to stop the bleeding.

First, commence hemostatic resuscitation, apply a pelvic binder and call both the trauma surgeon and the orthopod on call.

My preferred approach, if resources are available, would be to take the unstable patient to the operating theatre for preperitoneal packing and pelvic fixation (with treatment of any other injuries that may contribute to hemodynamic instability using the principles of damage control surgery) followed by urgent angiography if ongoing bleeding, instability or otherwise indicated.

There are 3 management options that can be performed in combination and in different orders:

- Angiography with embolisation

- Packing

- Mechanical stabilisation by external fixation

Angiography with embolisation

- In centers with interventional radiology capability immediately available these patients may be taken to the angiography suite for embolization.

- This treats arterial bleeding, which though still less common than venous bleeding, occurs more frequently in persistently hypotensive patients.

- Either selective embolisation or non-selective embolisation can be performed.

Packing

- Packing primarily stems venous bleeding, but the patient may be transferred for angiography post-packing.

- This may be performed by the increasingly popular and rapid technique of pre-peritoneal packing (see Weingart on Pelvic Trauma and below) or by direct retroperitoneal packing during laparotomy.

Mechanical stabilization by external fixation

- Mechanical stabilization by external fixation can be performed in the angiography suite or the operating theatre, or even in the ED in some centers.

- This helps reduce bleeding from the venous plexus and from cancellous bone. This can be performed regardless of which of the above two approaches are taken.

- External fixation does not offer any advantages over pelvic binding in the initial management of pelvic fractures, although pelvic binders may impair surgical access.

Definitive imaging (CT abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast) and treatment of pelvic fractures (e.g. open reduction and internal fixation) can be performed once the patient has stabilized following damage control resuscitation.

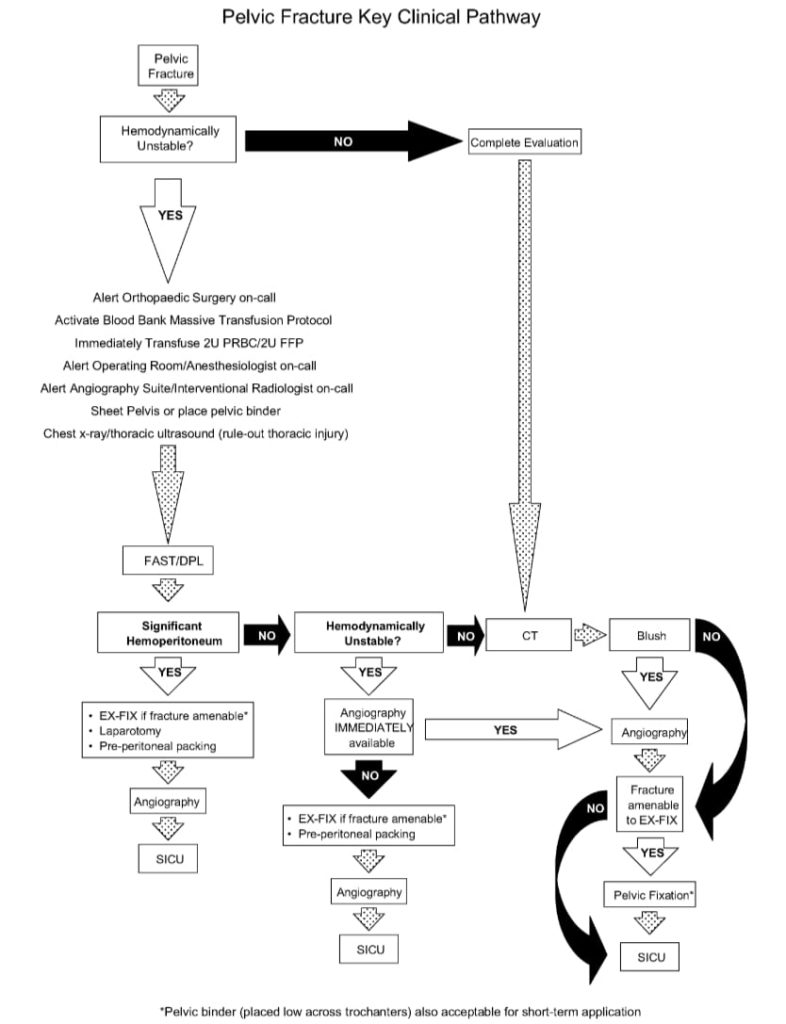

Here is a suggested management algorithm from White et al (2009):

Finally, remember that:

Isolated hemodynamically unstable pelvic trauma is uncommon — there are usually associated injuries due to the high energy mechanism of injury.

Learn more:

- Resus.ME — Exsanguinating pelvis – occlude the aorta

- The Trauma Professional’s Blog — Bleeding And Pelvic Fractures

- The Trauma Professional’s Blog — Predicting Bleeding In Patients With Stable Pelvic Fractures

- The Trauma Professional’s Blog — Pelvic Fractures: OR vs Angio In The Unstable Patient

- Trauma.org — Management of exsanguinating pelvis injuries

Q8. Which pelvic fracture patients should have angiography performed?

Answer and interpretation

These patients should have angiography performed (based on the 2011 EAST guidelines):

- hemodynamically unstable patients (probably best to perform preperitoneal packing in the operating theatre first)

- patients with a pelvic “blush” on CT with IV contrast usually require selective embolisation even if stable

- ongoing bleeding after angiography should get repeat angiography

- elderly patients (e.g. > 60 years old) with major pelvic fractures should get angio even if stable

- Pelvic hematoma volume > 500 mL predicts the need for angiography

Note that neither fracture pattern nor pelvic hematoma location reliably predicts the need for angiography, and even patients with pubic ramus fractures or isolated acetabular fractures may require angiography.

Q9. What are the pros and cons of angiography and embolisation for pelvic fractures?

Answer and interpretation

The pros:

- can identify and control arterial hemorrhage from pelvic fractures

- 85 to 100% effective in controlling arterial hemorrhage

- embolisation can be performed selectively (just the bleeding vessel) or non-selectively (bilateral internal iliac arteries)

- can be repeated if ongoing bleeding (e.g. a bleeding artery may have been in vasospasm during the initial procedure)

- the procedure is considered safe — reports of gluteal necrosis are likely due to trauma rather than angioembolisation, and rates of sexual dysfunction in men are not increased

- does not require laparotomy for direct retroperitoneal packing

- avoids attempts at direct surgical ligation of bleeding arteries, which results in universally poor outcomes

- may be possible to embolise other bleeding vessels (e.g. splenic or hepatic arteries)

The cons:

- not beneficial for venous or bone hemorrhage, which are the sources of most hemorrhage from pelvic trauma (up to 90%)

- limited availability

- frequently delayed even when available… even in Level 1 trauma centers in the US (1-5 hours is typically reported in the literature)

- requires skilled staff and substantial resources

- requires careful communication, coordination, on call rosters and agreed upon hospital protocols

- prolonged procedure (mean 90 minutes)

- arterial bleeding sometimes stops spontaneously, and does not always need angioembolisation

- not suitable for truly unstable patients as not performed in operating theatres where resuscitation and definitive surgery is more easily performed

- risk of complications (e.g. femoral artery injury from venous access, radiation exposure, contrast allergy, contrast induced nephropathy, ischemia from embolisation)

- selective embolisation is associated with increased rates of recurrent or ongoing hemorrhage

- access to the femoral artery may be difficult (e.g. obesity, associated trauma)

Q10. How is pre-peritoneal packing performed?

Answer and interpretation

Pre-peritoneal packing is a method of directly packing the retroperitoneum without the need for a laparotomy.

The 2011 EAST guidelines describe the procedure as follows:

- a midline incision 8 cm in length just above the pubis extending toward the umbilicus.

- Skin and subcutaneous tissue is opened in the midline, as is the fascia.

- The bladder is retracted away from the fracture and three laparotomy pads are placed in the retroperitoneal space on each side toward the iliac vessels.

- The procedure is repeated on the opposite side and the fascia and skin are closed.

Packs are usually left in situ for 24-48 hours. Pretty simple, eh.

Q11. What are the pros and cons of preperitoneal packing for pelvic fractures?

Answer and interpretation

The pros:

- often successful at controlling hemorrhage in retrospective studies (>80% of cases)

- can be performed in 20 minutes by experienced surgeons

- easy to learn and perform

- especially useful if angiography is unavailable or if there is a delay in its availability

- can be used to rescue failed angiography

- can be performed at smaller centers prior to transfer to a trauma center for definitive angiography

- can be performed concurrently with pelvic fixation and other surgical procedures

- does not require laparotomy for direct retroperitoneal packing and is not associated with increased rates of abdominal compartment syndrome

- less invasive than laparotomy with minimal blood loss

The cons:

- fails to control hemorrhage in about 15% of cases

- unlikely to control arterial hemorrhage

- not all general surgeons are familiar with the technique

- requires operating theatre, staff and resources

- no prospective head-to-head studies with angiography for first line treatment in the management of hemodynamically unstable pelvic fractures have been performed

- may increase rate of pelvic infections

- patient needs to return to the operating theatre for removal of packs

References

litfl.com

- Weingart on Pelvic Trauma

- Pelvic and Hip injuries in the Emergency Department

- Trauma Tribulation 026 — Trauma! Genitourinary injuries

Journal articles and textbooks

- Cullinane DC, Schiller HJ, Zielinski MD, Bilaniuk JW, Collier BR, Como J, Holevar M, Sabater EA, Sems SA, Vassy WM, Wynne JL. Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma practice management guidelines for hemorrhage in pelvic fracture–update and systematic review. J Trauma. 2011 Dec;71(6):1850-68. Review. PubMed PMID: 22182895.

- Fildes J, et al. Advanced Trauma Life Support Student Course Manual (8th edition), American College of Surgeons 2008.

- Heetveld MJ, Harris I, Schlaphoff G, Sugrue M. Guidelines for the management of haemodynamically unstable pelvic fracture patients. ANZ J Surg. 2004 Jul;74(7):520-9. Review. PubMed PMID: 15230782.

- Legome E, Shockley LW. Trauma: A Comprehensive Emergency Medicine Approach, Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Marx JA, Hockberger R, Walls RM. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice (7th edition), Mosby 2009. [mdconsult.com]

- Suzuki T, Smith WR, Moore EE. Pelvic packing or angiography: competitive or complementary? Injury. 2009 Apr;40(4):343-53. Epub 2009 Mar 17. Review. PubMed PMID: 19278678.

- White CE, Hsu JR, Holcomb JB. Haemodynamically unstable pelvic fractures. Injury. 2009 Oct;40(10):1023-30. Epub 2009 Apr 16. Review. PubMed PMID: 19371871.

Social media and other web resources

- EMCrit — Severe Pelvic Trauma

- EMRAP November 2006 — Carlos Brown: Pelvic Exsanguination (subscription required)

- Free Emergency Medicine Talks — Thomas Scalea 2010: Pelvic Trauma

- Free Emergency Medicine Talks — Julie Gorchynski 2011: Stabilizing Pelvic Fractures: Is Anything New?

- Free Emergency Medicine Talks — Sachin Shah 2010: Pelvic Fractures

CLINICAL CASES

Trauma Tribulation

Chris is an Intensivist and ECMO specialist at The Alfred ICU, where he is Deputy Director (Education). He is a Clinical Adjunct Associate Professor at Monash University, the Lead for the Clinician Educator Incubator programme, and a CICM First Part Examiner.

He is an internationally recognised Clinician Educator with a passion for helping clinicians learn and for improving the clinical performance of individuals and collectives. He was one of the founders of the FOAM movement (Free Open-Access Medical education) has been recognised for his contributions to education with awards from ANZICS, ANZAHPE, and ACEM.

His one great achievement is being the father of three amazing children.

On Bluesky, he is @precordialthump.bsky.social and on the site that Elon has screwed up, he is @precordialthump.

| INTENSIVE | RAGE | Resuscitology | SMACC