Wide, Complex and Troublesome

aka Cardiovascular Curveball 013

A junior colleague asks if he can discuss a case with you.

His patient is a 23 year-old man who presents with 2 hours of rapid regular palpitations associated with ‘not feeling quite right’. These symptoms came on while he was running on a treadmill at his local gym. He has no significant past medical history. Apart from a tachycardia, examination is unremarkable and he is hemodynamically stable.

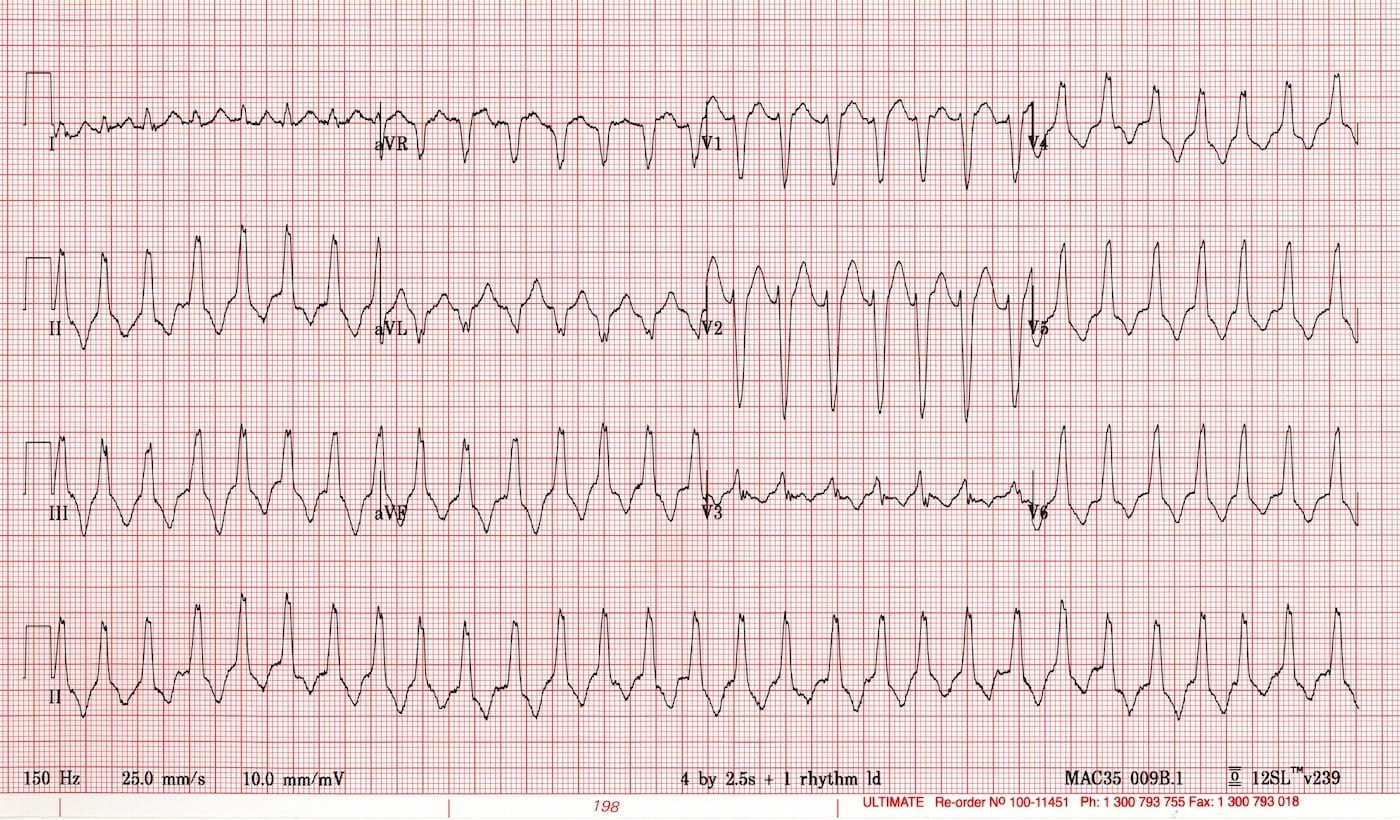

This is his ECG:

Questions

Q1. Describe the ECG.

Answer and interpretation

Key features include:

- Broad complex regular tachycardia (~170/min)

- Normal axis (“inferior axis”, nearly + 90 degrees)

- Indistinct P waves

- LBBB-like QRS morphology

- QRS complexes are not concordant throughout the chest leads

- T waves discordant with QRS complexes

Your colleague says he thinks it is an SVT with aberrant conduction because the patient is young, haemodynamically stable and has no history of heart disease.

Q2. What is your response?

Answer and interpretation

That’s an interesting thought… but:

None of these features, even in combination, can reliably distinguish between VT and SVT with aberrancy.

You can learn more about the difficulties in diagnosing VT versus SVT with aberrancy from the ECG Library.

Your colleague suggests, citing the 2010 ILCOR guidelines, that adenosine could be administered and if the patient reverts then the diagnosis of SVT with aberrancy will be confirmed.

Q3. What is your response to this suggestion?

Answer and interpretation

Cardioversion in response to adenosine does not rule out VT.

Adenosine can revert VT… and won’t revert all cases of SVT with (or without) aberrancy.

In fact adenosine-sensitive VT is more likely in younger patients with structurally normal hearts and no coronary artery disease. Whether VT will be responsive to adenosine cannot be reliably predicted from an ECG.

However, it is not dangerous to use adenosine in this setting — it just can’t be relied upon to make the diagnosis.

But what about the 2010 ILCOR guidelines?

The recent 2010 ILCOR guidelines (see Deakin et al, 2010) states that:

- “Adenosine may aid in diagnosing VT, but it will not terminate it (LOE 4)”

and

- “In undifferentiated regular stable wide-complex tachycardia, IV adenosine may be considered relatively safe, may convert the rhythm to sinus, and may help diagnose the underlying rhythm.”

The papers by Hina et al (1996) and Lenk et al (1997) (the latter is a pediatric case series) found that VT did cardiovert with adenosine in over half of their cases! (I got these references from Mattu (2011)). These papers suggests that the ILCOR recommendations are wrong.

Do not use adenosine in an irregular wide complex tachycardia — you may precipitate VF!

Q4. How can VT and SVT be reliably distinguished?

Answer and interpretation

Identification of certain features on the ECG can rule in VT:

- AV dissociation

- fusion beats

- capture beats

But these are only present in about 20% of cases of VT.

In the absence of these features, VT or SVT with aberrancy are possible. A number of algorithms have been proposed to help distinguish VT from SVT with aberrancy (e.g. Brugada, Vereckei) but nothing can completely rule out VT.

However, if a baseline or previous ECG is available then SVT with aberrancy can be diagnosed with some certainty if the QRS morphology of the wide complex tachycardia is identical to the QRS morphology when the patient was previously in sinus rhythm.

Otherwise, electrophysiological studies are the definitive diagnostic investigation.

Learn more by reading VT versus SVT with aberrancy from the ECG Library.

Q5. How would you treat this patient?

Answer and interpretation

You know the drill — if in doubt, treat as VT!

First, remember to seek and treat underlying causes such as ischemia, metabolic disturbance (e.g. hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia) and prescribed or recreational drug use. Doing so may lead to cardioversion directly, or increase the chance that other treatment options are successful.

The other treatment options are electrical and chemical cardioversion. I generally prefer the former, but it’s worth discussing the options with your patient if he or she is stable.

Electrical cardioversion

- Provide procedural sedation (e.g. propofol IV) prior to electrical cardioversion (e.g. synchronous, 100J biphasic) in a monitored setting equipped for resuscitation, after obtaining consent.

Chemical cardioversion is the alternative. Options include:

- Procainamide probably the best option for chemical cardioversion of VT despite slower onset, but can cause hypotension and QRS widening/ long QT…

The main drawback is that it is not currently available in Australia! - Amiodarone this drug is less effective than many believe — perhaps only about 30% of cases of VT are successfully cardioverted. It’s evidence rating was downgraded in the last ILCOR guidelines.

- Sotalol more effective than lignocaine, but causes long QT.

- Magnesium in general, if you don’t consider magnesium as a potential therapy for a condition you are not an emergency physician.

- Lignocaine only effective about a quarter of the time.

Remember:

If the patient becomes unstable… start charging!

Q6. What was the diagnosis in the above ECG?

Answer and interpretation

Right Ventricular Outflow Tachycardia

Most types of VT do not cardiovert following adenosine treatment, but this form of VT is usually adenosine-sensitive. Adenosine sensitivity of VT is heterogenous, and (again…) cannot be reliably predicted from the ECG. Past episodes of adenosine responsiveness would suggest that a current episode will also respond.

Adenosine-sensitive types of VT are typically catecholamine-induced (often occurring during exercise) and may arise from any part of the right or left ventricles. A small minority of fascicular VTs respond to adenosine as do some ischemia-related VTs. It’s all a bit murky, and nothing seems certain!

Learn more about Right Ventricular Outflow Tachycardia and Fascicular VT in the ECG Library.

References

- Cummins RO, Hazinski MF. The quest for a terminator. Ann Emerg Med. 2006 Mar;47(3):227-9. Epub 2006 Jan 25. PMID: 16492487.

- Deakin CD, Morrison LJ, Morley PT, Callaway CW, Kerber RE, Kronick SL, Lavonas EJ, Link MS, Neumar RW, Otto CW, Parr M, Shuster M, Sunde K, Peberdy MA, Tang W, Hoek TL, Böttiger BW, Drajer S, Lim SH, Nolan JP; Advanced Life Support Chapter Collaborators. Part 8: Advanced life support: 2010 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science with Treatment Recommendations. Resuscitation. 2010 Oct;81 Suppl 1:e93-e174. PMID: 20956032.

- Hina K, Kusachi S, Takaishi A, Yamasaki S, Sakuragi S, Murakami T, Kita T. Effects of adenosine triphosphate on wide QRS tachycardia. Analysis in 18 patients. Jpn Heart J. 1996 Jul;37(4):463-70. PMID: 8890760.

- Jane-Wit D, Batsford W, Malm B. Ischemic etiology for adenosine-sensitive fascicular tachycardia. J Electrocardiol. 2011 Mar-Apr;44(2):217-21. Epub 2010 Sep 15. PMID: 20832812.

- Lenk M, Celiker A, Alehan D, Koçak G, Ozme S. Role of adenosine in the diagnosis and treatment of tachyarrhythmias in pediatric patients. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1997 Oct;39(5):570-7. PMID: 9363655.

- Marill KA, Greenberg GM, Kay D, Nelson BK. Analysis of the treatment of spontaneous sustained stable ventricular tachycardia. Acad Emerg Med. 1997 Dec;4(12):1122-8. PMID: 9408427.

- Marill KA, deSouza IS, Nishijima DK, Senecal EL, Setnik GS, Stair TO, Ruskin JN, Ellinor PT. Amiodarone or procainamide for the termination of sustained stable ventricular tachycardia: an historical multicenter comparison. Acad Emerg Med. 2010 Mar;17(3):297-306. PMID: 20370763.

- Mattu, A. The Pinnacle: ECG cases that would make an electrophysiologist blush. Presentation at the 2011 ACEP Scientific Assembly. [pdf of slideshow]

- Neumar RW, Otto CW, Link MS, Kronick SL, Shuster M, Callaway CW, Kudenchuk PJ, Ornato JP, McNally B, Silvers SM, Passman RS, White RD, Hess EP, Tang W, Davis D, Sinz E, Morrison LJ. Part 8: adult advanced cardiovascular life support: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010 Nov 2;122(18 Suppl 3):S729-67. Review. Erratum in: Circulation. 2011 Feb 15;123(6):e236. PMID: 20956224. [Free Fulltext]

- Tomlinson DR, Cherian P, Betts TR, Bashir Y. Intravenous amiodarone for the pharmacological termination of haemodynamically-tolerated sustained ventricular tachycardia: is bolus dose amiodarone an appropriate first-line treatment? Emerg Med J. 2008 Jan;25(1):15-8. PMID: 18156531.

CLINICAL CASES

Cardiovascular Curveball

Chris is an Intensivist and ECMO specialist at The Alfred ICU, where he is Deputy Director (Education). He is a Clinical Adjunct Associate Professor at Monash University, the Lead for the Clinician Educator Incubator programme, and a CICM First Part Examiner.

He is an internationally recognised Clinician Educator with a passion for helping clinicians learn and for improving the clinical performance of individuals and collectives. He was one of the founders of the FOAM movement (Free Open-Access Medical education) has been recognised for his contributions to education with awards from ANZICS, ANZAHPE, and ACEM.

His one great achievement is being the father of three amazing children.

On Bluesky, he is @precordialthump.bsky.social and on the site that Elon has screwed up, he is @precordialthump.

| INTENSIVE | RAGE | Resuscitology | SMACC

Nice case. I’m wondering if there’s any evidence that cardioversion in response to vagal maneuvers rules in SVT (versus VT). I had a recent case for which this was my justification for concluding the pt had SVT (in addition to other reassuring risk features like young age and benign PMH) but I can’t claim to have read that anywhere.

Here is my systematic analysis. It meets brugada criteria. Dx VT.

Looking for general signs of VT:

– Very broad complexes > 160ms? No.

– Extreme northwest axis? No. aVF and I are positive.

– Lead II Brugada RWPT > 50ms? No. It is about 40ms here.

Then go down the Brugada algorithm.

– Absence of RS complexes in all precordial leads? Ie. All leads pointing one way? No.

– RS > 100ms (2.5 blocks) in any precordial leads? No. they measure about 50ms.

– AV dissociation? **** Possible – buried P waves in rhythm strip. ***

– BBB pattern? Yes – S in V1 so LBBB morphology.

— BBB general morphology criteria: V6 QS waves? No. V6 R/S <1? No.

— LeftBBB specific morphology criteria:

—— V1 Josephson notch? No;

—— **** V1 RS > 60ms? YES! Measures almost 80ms. ****

Dx VT.

i’ll be honest – wouldnt have picked RVOT VT on initial review.