Pelvic Trauma

Reviewed and revised 6 June 2016

OVERVIEW

Pelvic fractures are important in critical care because they are associated with:

- High energy mechanisms, such as:

- motor vehicle crashes

- collisions with pedestrians

- falls from height

- Major haemorrhage, which can be difficult to control

- Other major injuries

- Intra-abdominal organs (28%), including aortic injury

- Hollow viscus injury (13%)

- Rectal injury (up to 5%)

- High morbidity and mortality (overall mortality is 10-30%; up to 50% if shocked)

Note that stable pelvic fractures (Tile Class A) that do not involve the pelvic ring (e.g. pubic ramus fractures and avulsion fractures) are associated with much less morbidity.

CLASSIFICATION OF PELVIC FRACTURES

There are various systems for classification, these are the 2 most often used:

- Tile classification

- based on pelvic stability and useful for guiding pelvic reconstruction

- Young-Burgess classification

- more useful in the ED as it is based on mechanism and also indicates stability (I to III sub-classification)

See Classification of Pelvic Fractures

HAEMORRHAGE FROM PELVIC FRACTURES

There are 4 potential sources:

- Surfaces of fractured bones

- Pelvic venous plexus

- Pelvic arterial injury (see Pelvic arterial injury)

- Extra-pelvic sources (present in 30% of pelvic fractures)

Classically venous hemorrhage is said to account for 90% of bleeding from pelvic fractures, and arterial only 10%.

- However arterial bleeding is more common than this in patients that have ongoing hemorrhage (e.g. despite pelvic binding or mechanical stabilisation) or have hemodynamic compromise.

Suzuki et al (2008) point out that “Haemorrhage from pelvic fracture is essentially bleeding into a free space, potentially capable of accommodating the patient’s entire blood volume without gaining sufficient pressure-dependent tamponade.”

- although true pelvic volume is about 1.5L this is increased with disruption of the pelvic ring

- the tamponade effect of the pelvic ring is lost in severe pelvic fractures with disruption of the parapelvic fascia

- pelvic fractures cause bleeding into the retroperitonal space, even when intact the retroperitoneal space can accumulate 5L of fluid with a pressure rise of only 30 mmHg

- hemorrhage can escape into the peritoneum and thighs with disruption of the pelvic floor (e.g. open book fractures)

Hemodynamically unstable open pelvic fractures have mortality rates as high as 70%.

CLINICAL ASSESSMENT

Assessment for pelvic trauma should be part of a coordinated, structured assessment for multiple traumatic injuries (e.g. ATLS approach)

- Assessment of the pelvis should be performed with extreme care

- Inspect:

- ecchymosis, deformity, asymmetry, wounds

- Palpate the skeletal structures:

- pubic symphysis, iliac crests, the posterior sacroiliac joints, ischial tuberosities as well as the the spine extending inferiorly to the sacrum and coccyx

- Assess for mobility:

- Gently compress the iliac crests to fell for instability

- If there is no pain or movement felt on compression, gently distract the iliac crests (some experts, such as Scott Weingart, advise against distraction)

- A gentle technique and cautious approach is important to avoid aggravating haemorrhage if the pelvis is fractured

- This maneuver should only be performed once, ideally by the most senior trauma doctor present.

- Do not ‘rock’ the pelvis!

- Patients with suspected pelvis fractures also need careful examination of:

- Rectum — digital rectal exam to palpate for rectal injury (e.g. blood, wounds), bony fragments, sphincter function and a boggy or high-riding prostate

- Perineum and genitalia — check for coexistent genital trauma, blood at the meatus, and scrotal or other perineal hematomas. Perform a vaginal exam in women for vaginal tears.

- Lower limb length discrepancy and malrotation, and neurology

- The abdomen, e.g. tenderness, distention, external signs of trauma

Normal examination in an alert adult patient effectively rules out significant pelvic injury (93-100% sensitivity) unless there are distracting injuries. Any injuries missed in this circumstance tend to be clinically insignificant or only require managed conservatively.

INVESTIGATIONS

Bedside tests

- Venous blood gas (VBG)

- monitor hemoglobin (Hb), lactate and acidemia in major haemorrhage

- FAST scan

- assess for intraperitoneal fluid in a hemodynamically unstable patient with suspected pelvic fracture

- Positive scan suggests haemorrhage from intra-abdominal injury and the need for laparotomy

- False positives may result from associated bladder rupture

- Diagnostic peritoneal aspirate (DPA)

- can be used to rule out a false negative FAST scan in a haemodynamically unstable patient

- DPA is performed above the umbilicus in patients with suspected pelvic fractures to avoid aspirating a pelvic hematoma

- A positive result is the aspiration of 10 mL of frank blood or GI contents

- this is an open procedure performed by a surgeon skilled in the technique, and may take 20 minutes

Laboratory tests

- Group and save, or cross match (4-8 units) if severely injured

- full blood count and coagulation profile

- baseline Hb to allow monitoring for a drop over time as a result of hemorrhage

- platelets and clotting factors may be depleted in major haemorrhage

- BhCG in women of child bearing age

Imaging

- AP pelvis x-ray

- a normal x-ray does not exclude pelvic fractures completely, but does rule out pelvic fracture as a cause of haemodynamic instability

- Indications for pelvis x-ray include:

- Hemodynamically unstable

- Altered mental state

- Distracting injuries

- Children (physical exam is less reliable)

- Abdominopelvic CT not being done for another reason

- Do not perform pelvis x-ray if:

- Normal examination and the patient is alert and able to ambulate

- Abdominopelvic CT will be performed anyway for another reason

- CT abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast

- imaging modality of choice for assessing pelvic ring injury

- performed in the haemodynamically stable patient to rule out intra-abdominal and retroperitoneal injury, and to characterize the type and severity of pelvic injury and may identify those suited to inetrventional radiology

- Angiography

- used to identify arterial injury and to guide embolisation

Additional comments:

- Note that the miss rate for pelvic fractures using plain films varies from about 4 to 23% in different studies, and other studies comparing radiographs to CT scans indicates that the sensitivity of pelvic radiographs is only 64-78%.

- Even when an injury is detected by plain radiography, CT is generally necessary to further delineate the nature of injury and rule out other injuries.

ASSOCIATED INJURIES

Abdominal and gastrointestinal injuries

- Rectal injury is common (up to 5%), other intestinal injury may also occur (up to 5%)

- signifies an open fracture — which are more likely to be hemodynamically unstable

- may require fecal diversion, pre-sacral drainage and perineal debridement

- Risk of death from secondary sepsis

- In addition, there may be injury to spleen and liver (12%)

Genitourinary injuries

- Bladder and urethral injury (5-20%)

- urethral

- posterior urethra with pelvic fractures

anterior urethra with straddle injuries

- posterior urethra with pelvic fractures

- bladder: intra- and/or extraperitoneal

- vaginal tears (<5% in females; signifies and open fracture)

Other injuries (e.g. head, chest) may also be present, especially as the presence of pelvic fractures implies a high energy mechanism of injury.

COMPLICATIONS

Acute

- major haemorrhage and shock (leading mechanism of death)

- laceration of venous structures

- arterial injury (e.g. branches of internal iliac)

- visceral and soft tissue injury:

- fractures may be compound into the perineum or vagina

- lacerations into the rectum or bladder

- urethral injuries common in males

- nerve injury

- sacral plexus injury; e.g. S2-5 sacral nerve root injuries with sacral fracutres

- injuries to L4/5 or S1 nerve roots

- ileus

- fat embolization

- acute respiratory distress syndrome

- venous thromboembolism

- abdominal compartment syndrome

Late

- infection (second most common mechanism of death)

- fracture complications (e.g. osteoarthritis, malunion)

- disability and immobility

- incontinence

- sexual dysfunction

- dystocia following subsequent pregnancy

MANAGEMENT

Resuscitation

- Coordinated team-based ATLS approach to address immediate life threats and identify other potential serious injuries

- commence haemostatic resuscitation if appropriate

- pelvic stabilization (See Pelvic stabilization)

- avoid unnecessary movement of patient

- apply a pelvic binder early

- pelvic binder should be applied before intubation (if required), as neuromuscular blockade may allow pelvic volume to expand

Specific initial management if haemodynamically stable:

- apply a pelvic binder

- perform an abdominopelvic CT with IV contrast +/- CT cystography to identify abdominal and pelvic injuries and allow prioritisation of management

- A pelvic ‘blush’ indicates the need for angiography and selective embolisation of the actively bleeding artery

- non-emergent surgical fixation as require

Specific initial management if haemodynamically unstable:

- Commence haemostatic resuscitation

- Apply pelvic binder

- Perform bedside tests:

- AP pelvis XR — if normal, rules out pelvic fracture as cause of haemodynamic instability

- EFAST — check for haemo/pneumothorax and intra-abdominal free fluid.

- If EFAST is negative, confirm absence of intraperitoneal blood using supra-umbilical DPA

- If pelvic fracture and:

- positive EFAST, or

- EFAST negative but DPA* positive

- then the patient requires emergency laparotomy, during which pelvic stabilization and/or pre-peritoneal pelvic packing is performed pending definitive management of the pelvic injury

- If the EFAST and DPA are negative, then the patient is treated as described below (i.e. hemodynamically unstable patient with isolated pelvic trauma)

- The patient may have an abdominopelvic CT with IV contrast +/- CT cystography once stabilized

Supportive care and monitoring

- including neurovascular observation

Seek and treat complications

Disposition

- disposition from the emergency department depends on the finding of the above investigations, may include:

- operating theatre

- interventional radiology suite

- intensive care unit

MANAGEMENT OF THE HAEMODYNAMICALLY UNSTABLE PATIENT WITH ISOLATED PELVIC TRAUMA

Isolated hemodynamically unstable pelvic trauma is uncommon

- there are usually associated injuries due to the high energy mechanism of injury

- the approach to the hemodynamically unstable patient with isolated pelvic trauma is controversial, and varies between centers according to available resources and local protocols.. The main goal is to stop the bleeding!

Approach

- commence haemostatic resuscitation

- apply a pelvic binder

- call the trauma surgeon, orthopod and interventional radiologist on call

- There are 3 management options that can be performed in combination and in different orders:

- Angiography with embolisation

- Packing

- Mechanical stabilisation by external fixation

Angiography with embolisation (see Angiography and embolisation in pelvic trauma)

- In centers with interventional radiology capability immediately available these patients may be taken to the angiography suite for embolization.

- This treats arterial bleeding, which though still less common than venous bleeding, occurs more frequently in persistently hypotensive patients.

- Either selective embolisation or non-selective embolisation can be performed.

Packing

- Packing primarily stems venous bleeding, but the patient may be transferred for angiography post-packing.

- This may be performed by the increasingly popular and rapid technique of pre-peritoneal packing (see Weingart on Pelvic Trauma and below) or by direct retroperitoneal packing during laparotomy.

Mechanical stabilization by external fixation

- Mechanical stabilization by external fixation can be performed in the angiography suite or the operating theatre, or even in the ED in some centers.

- This helps reduce bleeding from the venous plexus and from cancellous bone. This can be performed regardless of which of the above two approaches are taken.

- External fixation does not offer any advantages over pelvic binding in the initial management of pelvic fractures, although pelvic binders may impair surgical access.

Definitive imaging (CT abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast) and treatment of pelvic fractures (e.g. open reduction and internal fixation) can be performed once the patient has stabilized following damage control resuscitation

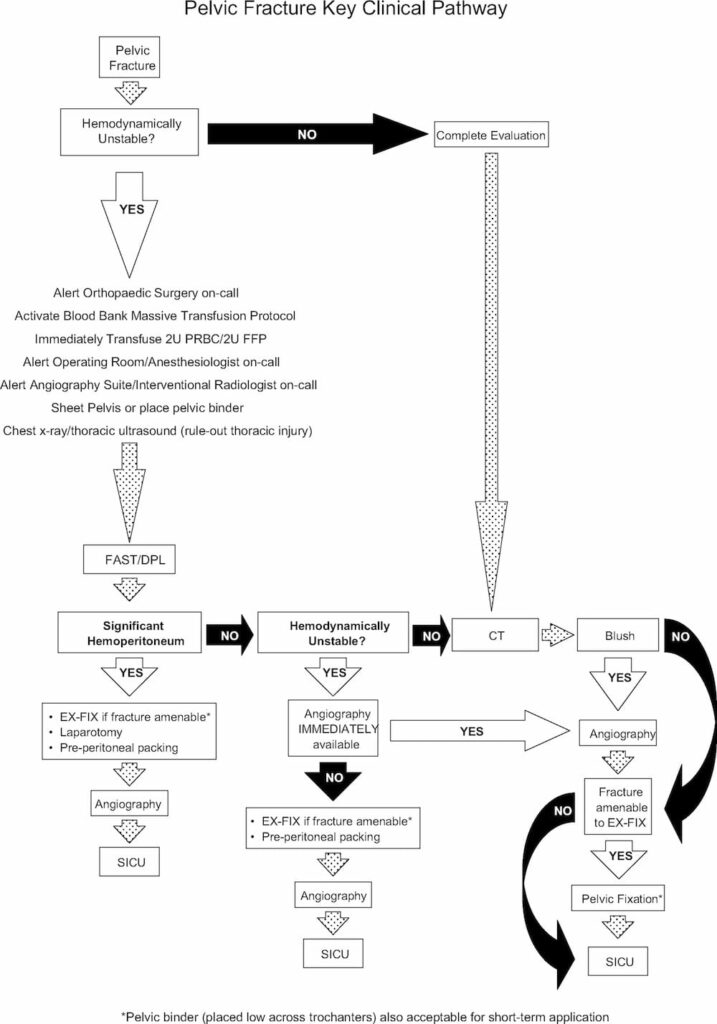

Here is a suggested management algorithm from White et al (2009):

References and Links

LITFL

- CCC — Pre-peritoneal packing

- CCC — Pelvic arterial injury

- CCC — Classification of Pelvic Fractures

- CCC — Pelvic stabilization

- CCC — Angiography and embolisation in pelvic trauma

- Weingart on Pelvic Trauma

- Pelvic and Hip injuries in the Emergency Department

- Trauma Tribulation 026 — Trauma! Genitourinary injuries

- Trauma Tribulation 027 — Trauma! Pelvic fractures I

- Trauma Tribulation 028 — Trauma! Pelvic fractures II

Journal articles and textbooks

- Cullinane DC, Schiller HJ, Zielinski MD, Bilaniuk JW, Collier BR, Como J, Holevar M, Sabater EA, Sems SA, Vassy WM, Wynne JL. Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma practice management guidelines for hemorrhage in pelvic fracture–update and systematic review. J Trauma. 2011 Dec;71(6):1850-68. Review. PubMed PMID:22182895.

- Heetveld MJ, Harris I, Schlaphoff G, Sugrue M. Guidelines for the management of haemodynamically unstable pelvic fracture patients. ANZ J Surg. 2004 Jul;74(7):520-9. Review. PubMed PMID: 15230782.

- Suzuki T, Smith WR, Moore EE. Pelvic packing or angiography: competitive or complementary? Injury. 2009 Apr;40(4):343-53. PMID: 19278678.

- White CE, Hsu JR, Holcomb JB. Haemodynamically unstable pelvic fractures. Injury. 2009 Oct;40(10):1023-30. Epub 2009 Apr 16. PMID: 19371871.

FOAM and other web resources

- EMCrit — Severe Pelvic Trauma

Critical Care

Compendium

Chris is an Intensivist and ECMO specialist at The Alfred ICU, where he is Deputy Director (Education). He is a Clinical Adjunct Associate Professor at Monash University, the Lead for the Clinician Educator Incubator programme, and a CICM First Part Examiner.

He is an internationally recognised Clinician Educator with a passion for helping clinicians learn and for improving the clinical performance of individuals and collectives. He was one of the founders of the FOAM movement (Free Open-Access Medical education) has been recognised for his contributions to education with awards from ANZICS, ANZAHPE, and ACEM.

His one great achievement is being the father of three amazing children.

On Bluesky, he is @precordialthump.bsky.social and on the site that Elon has screwed up, he is @precordialthump.

| INTENSIVE | RAGE | Resuscitology | SMACC