Pulmonary Embolus pondering

aka Pulmonary Puzzler 018

A 52 year old bricklayer is transferred from another hospital with an acute episode of dizziness, palpitations and tachycardia. 2 days prior, he had bilateral total knee replacements for osteoarthritis.

Observations on arrival: P 120, BP 130/75, RR 22, SpO2 88% room air, 98% 4 litres via nasal prongs.

Bedside echo in Emergency showed Normal LV, dilated RV with moderate impairment, septal paradox (bowing RA septum towards left). Troponin I (high sensitivity) 4410 ng/L

This man has acute Pulmonary Embolus (PE)

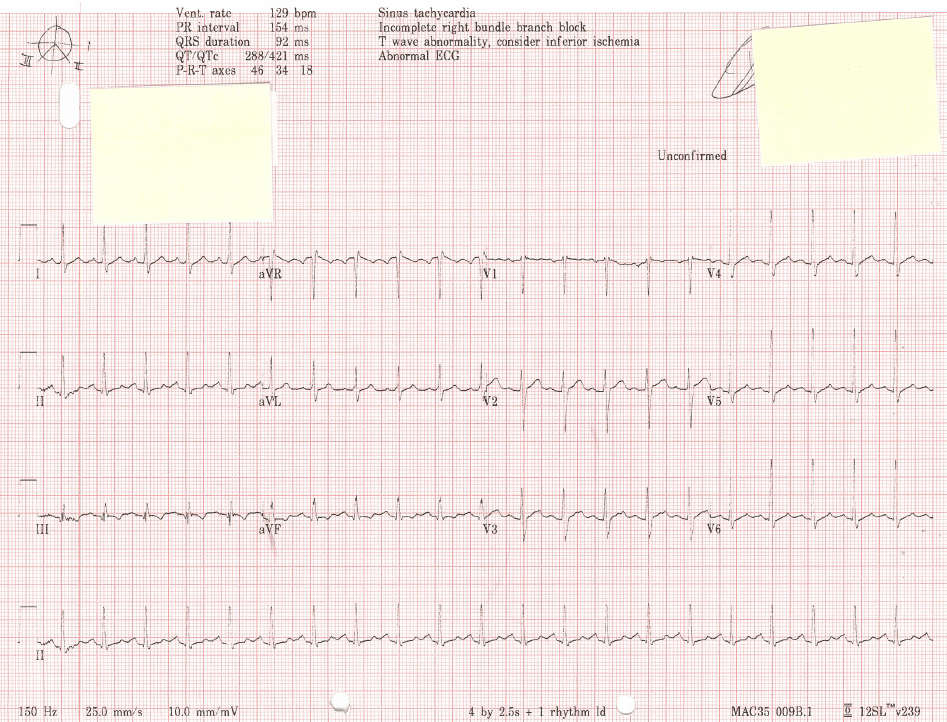

- His ECG demonstrates a normal axis, tachycardia and SI QIII TIII (see also ECG changes in PE).

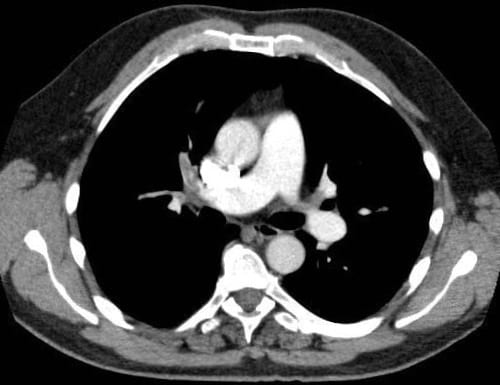

- His CTPA demonstrates an extensive clot in the right PA (and subsegmental clots on the left).

- There is evidence of right ventricular strain on echo and biochemical evidence of cardiac damage.

Questions, questions…

What are the treatment options? Does he need removal of the clot by some means? Possible treatment options in acute PE:

Answer and Interpretation

- Low molecular weight heparin and close observation

- Unfractionated heparin infusion

- IVC filter

- Thrombolysis

- Thrombectomy

- Catheter directed therapy

Quality evidence to inform the treatment of PE causing cardiovascular instability has been sparse for many years. The initial study published in 1995 examining the role of thrombolysis for ‘massive’ PE was stopped prematurely after n=8 were recruited and all subjects in the control (heparin) group died. This became the basis of our practice for many years. Whilst it is persuasive of the role of thrombolysis in ‘massive’ PE it does not represent good quality data, and certainly does not inform us of the role of thrombolysis in less severe PE.

How should we describe pulmonary embolus?

Answer and Interpretation

More recently PE has been described as high, intermediate and low risk. Clinical characteristics and objective measurements now define risk groups, and they have nothing to do with the appearance, whereabouts or volume of the clot on the CTPA.

Classification of acute PE:

- High risk (previously ‘massive’) PE patients have persistent shock or hypotension.

- Intermediate risk (previously ‘sub-massive’) PE is defined as the presence of right ventricular (RV) dysfunction and/or myocardial injury in the absence of hypotension.

- Low risk PE patients have none of these features and can probably be treated outside of hospital.

Until recently the role of thrombolysis in PE has been controversial with the short-term aim of early clot breakdown overshadowed by the very real risk of increased major bleeding episodes. We are not even sure if breaking down or removal of clot is necessary.

The pulmonary embolism thrombolysis (PEITHO) study was an international multicentre double blind RCT that investigated the efficacy and safety of tenecteplase in intermediate risk PE. 1006 normotensive subjects with confirmed PE, RV dysfunction and raised cardiac injury markers were enrolled and received either un-fractionated heparin and placebo, or un-fractionated heparin and tenecteplase (30-50mg).

The combined composite primary endpoint – death and/or haemodynamic decompensation within 7 days – was significantly reduced in the intervention arm (2.6% tenecteplase, 5.6% placebo; p=0.02).

So, does this make thrombolysis a good thing for intermediate-risk PE?

Answer and Interpretation

I don’t think so – and here is why.

Combined primary endpoints make interpretation of clinical studies very hard – to be taken on face value they assume equal importance of the 2 (combined) outcomes. In this case we can argue that death is a pretty important, finite outcome. Haemodynamic decompensation, however, is not as serious nor permanent as death and, if recognised and managed appropriately, does not necessarily lead to death. In the PEITHO study, mortality at 7 days was no different between the groups (1.2% tenecteplase, 1.8% placebo; p=0.42) and therefore the signal for the primary endpoint being ‘met’ was due to haemodynamic instability (1.6% tenecteplase, 5% placebo; p=0.0002). There was no difference in those undergoing rescue thrombolysis between the groups.

The really important difference to note between the study arms is that of major bleeding with tenecteplase. Major extracranial bleeds (6.3% vs. 1.2%) and haemorrhagic stroke (2.0% vs. 0.2%) are more common. Tenecteplase conferred a 10-fold increased likelihood of stoke; this figure is even more sobering when you consider that the trial specifically excluded those thought to be at risk of bleeding. This risk of bleeding showed a non-significant increase in those above 75 years old. These findings are supported by a large recent meta-analysis that found increased risk of bleeding complications after thrombolysis in those over 65 years old.

So, what will thrombolysis do to our intermediate risk acute PE patient?

Answer and Interpretation

It may reduce ‘haemodynamic instability’ over the next 7 days but it won’t save life from death related to the PE, and it might cause major bleeding (1 in 17 patients) or stroke (1 in 50 patients). I don’t think that is an acceptable trade off.

PEITHO has not examined long-term outcomes such as RV failure or pulmonary hypertension. While recognised, these outcomes are unusual post-PE and in my opinion frequently represent recurrent VTE rather than persistent, chronic PE.

Treatments not investigated in the PEITHO study include surgical thrombectomy, IVC filters and catheter directed therapy. These have significantly less evidence to support, or inform, their use than thrombolysis did. More of that another time.

Peitho was the Goddess of persuasion, seduction and charming speech. The PEITHO study persuades us of 2 conclusions:

- PE can (and should) be categorized into different risk groups (high, intermediate and low) based on objective clinical measurements;

- The use of thrombolysis in intermediate risk PE cannot be routinely recommended due to an unacceptable risk-benefit profile.

By contrast, this study supports the use of anticoagulation in normotensive patients with PE even though there may be RV dysfunction, and/or evidence of cardiac strain. Monitor closely, be brave and patient, give a bit of fluid to support the RV if necessary, but above all don’t panic. Douglas Adams was correct.

References

LITFL Resources

- ECG Changes in pulmonary embolus – LITFL

- Pulmonary Embolism – Critical Care compendium

- Puzzling out the PERC Rule

- Bedside Echo in Pulmonary Embolism

- Thrombolysis for submassive pulmonary embolus

References

- Jerjes-Sanchez C, Ramirez-Rivera A, de Lourdes Garcia M, Arriaga-Nava R, Valencia S, Rosado-Buzzo A, et al. Streptokinase and Heparin versus Heparin Alone in Massive Pulmonary Embolism: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of thrombosis and thrombolysis 1995;2:227-9. [PMID 10608028]

- Torbicki A, Perrier A, Konstantinides S, Agnelli G, Galie N, Pruszczyk P, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). European heart journal 2008;29:2276-315. [Reference and PDF]

- Meyer G, Vicaut E, Danays T, Agnelli G, Becattini C, Beyer-Westendorf J, et al. Fibrinolysis for patients with intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism. The New England journal of medicine 2014;370:1402-11. [NEJM]

- Chatterjee S, Chakraborty A, Weinberg I, Kadakia M, Wilensky RL, Sardar P, et al. Thrombolysis for pulmonary embolism and risk of all-cause mortality, major bleeding, and intracranial hemorrhage: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2014;311:2414-21. [PMID 24938564]

CLINICAL CASES

Pulmonary Puzzler

Prof Fraser Brims Curtin Medical School, acute and respiratory medicine specialist, immediate care in sport doc, ex-Royal Navy, academic| Top 100 CXR | Google Scholar | ICIS Course ANZ