Brainstem Rules of 4

Hands up who enjoyed learning the anatomy of the brainstem in medical school?

Hmm, thought so.

In 2005, Peter Gates published a superb paper titled:

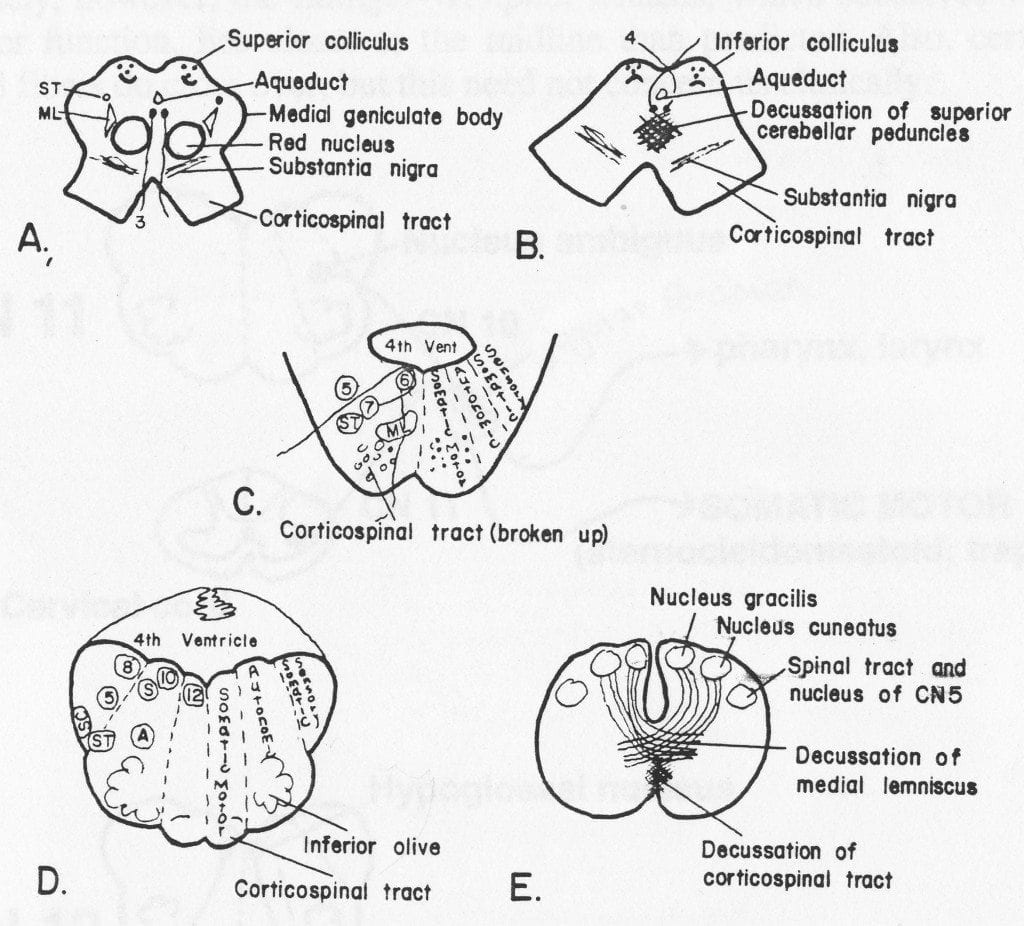

‘The rule of 4 of the brainstem: a simplified method for understanding brainstem anatomy and brainstem vascular syndromes for the non-neurologist’.

Gates described a simplified method for answering the question ‘Where is the lesion?’ using only the parts of the brainstem that we actually examine during a clinical examination to understand brainstem vascular syndromes.

Firstly, a quick review of the blood supply of the brainstem. Simply put the blood supply comes from:

- paramedian branches

- long circumferential branches (SAP)

- superior cerebellar artery (SCA)

- anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA)

- posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA)

And occlusion of these two groups of vessels results in two distinct types of brainstem syndrome:

- medial (or paramedian) brainstem syndromes ( due to para-median branch occlusion)

- lateral brainstem syndromes ( due to occlusion of the circumferential branches, also occasionally seen in unilateral vertebral occlusion)

And now the rules. If you can remember these rules the diagnosis of brainstem vascular syndromes becomes a pitifully simple exercise (?!) – here’s how it works:

In the rule of 4 there are 4 rules

- There are 4 structures in the ‘midline‘ beginning with M

- There are 4 structures to the ‘side‘ (lateral) beginning with S

- There are 4 cranial nerves in the medulla, 4 in the pons and 4 above the pons (2 in the midbrain)

- There are 4 motor nuclei that are in the midline are those that divide equally into 12 except for 1 and 2, that is 3, 4, 6 and 12 (5, 7, 9 and 11 are in the lateral brainstem)

The 4 medial structures and the associated deficits are:

- Motor pathway (or corticospinal tract): contralateral weakness of the arm and leg

- Medial Lemniscus: contralateral loss of vibration and proprioception in the arm and leg

- Medial longitudinal fasciculus: ipsilateral inter-nuclear ophthalmoplegia (failure of adduction of the ipsilateral eye towards the nose and nystagmus in the opposite eye as it looks laterally)

- Motor nucleus and nerve: ipsilateral loss of the cranial nerve that is affected (3, 4, 6 or 12)

The 4 ‘side’ (lateral) structures and the associated deficits are:

- Spinocerebellar pathway: ipsilateral ataxia of the arm and leg

- Spinothalamic pathway: contralateral alteration of pain and temperature affecting the arm, leg and rarely the trunk

- Sensory nucleus of the 5th cranial nerve: ipsilateral alteration of pain and temperature on the face in the distribution of the 5th cranial nerve (this nucleus is a long vertical structure that extends in the lateral aspect of the pons down into the medulla)

- Sympathetic pathway: ipsilateral Horner’s syndrome, that is partial ptosis and a small pupil (miosis)

According to Gates:

These pathways pass through the entire length of the brainstem and can be likened to ‘meridians of longitude‘ whereas the various cranial nerves can be regarded as ‘parallels of latitude‘. If you establish where the meridians of longitude and parallels of latitude intersect then you have established the site of the lesion.

The 4 cranial nerves in the medulla are CN 9-12:

- Glossopharyngeal (CN9): ipsilateral loss of pharyngeal sensation

- Vagus (CN10): ipsilateral palatal weakness

- Spinal accessory (CN11): ipsilateral weakness of the trapezius and stemocleidomastoid muscles

- Hypoglossal (CN12): ipsilateral weakness of the tongueThe 12th cranial nerve is the motor nerve in the midline of the medulla. Although the 9th, 10th and 11th cranial nerves have motor components, they do not divide evenly into 12 (using our rule) and are thus not the medial motor nerves.

The 4 cranial nerves in the pons are CN 5-8:

- Trigeminal (CN5): ipsilateral alteration of pain, temperature and light touch on the face back as far as the anterior two-thirds of the scalp and sparing the angle of the jaw.

- Abducent (CN6): ipsilateral weakness of abduction (lateral movement) of the eye (lateral rectus).

- Facial (CN7): ipsilateral facial weakness.

- Auditory (CN8): ipsilateral deafness.The 6th cranial nerve is the motor nerve in the medial pons. The 7th is a motor nerve but it also carries pathways of taste, and using the rule of 4 it does not divide equally in to 12 and thus it is not a motor nerve that is in the midline. The vestibular portion of the 8th nerve is not included in order to keep the concept simple and to avoid confusion. Nausea and vomiting and vertigo are often more common with involvement of the vestibular connections in the lateral medulla.

The 4 cranial nerves above the pons are CN 1-4:

- Olfactory (CN1): not in midbrain.

- Optic (CN2): not in midbrain.

- Oculomotor (CN3): impaired adduction, supradduction and infradduction of the ipsilateral eye with or without a dilated pupil. The eye is turned out and slightly down.

- Trochlear (CN4): eye unable to look down when the eye is looking in towards the nose (superior oblique).The 3rd and 4th cranial nerves are the motor nerves in the midbrain.

Thus a medial brainstem syndrome will consist of the 4 M’s and the relevant motor cranial nerves, and a lateral brainstem syndrome will consist of the 4 S’s and either the 9-11th cranial nerve if the lesion is in the medulla, or the 5th, 7th and 8th cranial nerve if the lesion is in the pons.

Handy tip: If there are signs of both a lateral and a medial (paramedian) brainstem syndrome, then one needs to consider a basilar artery problem, possibly an occlusion.

I’ll let you mull over these rules until the next ‘brainstem’ post, where you’ll be able to test drive ‘Gates’ Brainstem Rules of 4′ on some clinical scenarios.

References

- Gates P. The rule of 4 of the brainstem: a simplified method for understanding brainstem anatomy and brainstem vascular syndromes for the non-neurologist. Internal Medicine Journal 2005; 35: 263-266 [PMID 15836511]

- Goldberg S. Clinical Neuroanatomy Made Ridiculously Simple. MedMaster Series, 2000 Edition.

- Patten J. Neurological Differential Diagnosis. Springer-Verlag.

LITFL Links

- Brainstem Rules of 4 (original rules)

- Helpful Brainstem Figures (original figures)

- The rule of 4 of the brainstem (Rules re-imagined)

- A spider called Willis

- Using the Brainstem 1

- Using the Brainstem 2

- The Magic of the Neuro Exam

- Look Left, Look Right (Internuclear Ophthalmoplegia)

- More Befuddling Pupillary Asymmetry (Horner Syndrome)

Chris is an Intensivist and ECMO specialist at The Alfred ICU, where he is Deputy Director (Education). He is a Clinical Adjunct Associate Professor at Monash University, the Lead for the Clinician Educator Incubator programme, and a CICM First Part Examiner.

He is an internationally recognised Clinician Educator with a passion for helping clinicians learn and for improving the clinical performance of individuals and collectives. He was one of the founders of the FOAM movement (Free Open-Access Medical education) has been recognised for his contributions to education with awards from ANZICS, ANZAHPE, and ACEM.

His one great achievement is being the father of three amazing children.

On Bluesky, he is @precordialthump.bsky.social and on the site that Elon has screwed up, he is @precordialthump.

| INTENSIVE | RAGE | Resuscitology | SMACC