Is COVID-19 ARDS? What about lung compliance?

COVID-19: Keeping the baby in the bath (Part 3)

All models are wrong, but some are useful”

George Box 1976

Another “paradigm shift” is the argument that acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is now newly broken, that COVID-19 is not ARDS, and that established ARDS therapies are inappropriate for COVID-19 patients or may cause harm.

ARDS is an acute syndrome of hypoxia (P/F ratio <300) and bilateral lung opacities on imaging not fully explained by a cardiogenic cause or fluid overload (ARDS Definition Task Force, 2012). ARDS is not a disease. ARDS has always been a heterogeneous mix of different diseases. It would be surprising if the pathogenesis and progression of ARDS did not vary, at least in the beginning, considering how different “direct” causes like bacterial pneumonia and “indirect” causes such as pancreatitis are. Whether ARDS represents a “final common pathway” of lung injury, iatrogenic insults (such as fluid overload or ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI)), or host responses, is debatable. Diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) is often regarded as the key pathological finding in ARDS, and is being seen in autopsies of COVID-19 patients (Barton et al, 2020; Tian et al, 2020). However, others argue that DAD is not a universal feature of COVID-19 pneumonia at autopsy (Magro et al, 2020). So does this mean that COVID-19 is not ARDS? We don’t think so, because even before the COVID-19 pandemic, less than 50% of all ARDS patients had DAD at autopsy (Thille et al, 2013). ARDS has always been a construct in the minds of clinicians and researchers. It exists not because it is perfect, but because it has utility. It has utility for clinicians as it gives us a frame of reference for categorising patients, providing appropriate therapies, and prognosticating. It has utility for research as it allows otherwise heterogeneous patient groups to be studied in adequately powered clinical trials and provides a touchstone for new concepts and discoveries.

So, do COVID-19 patients have ARDS? They do if they meet the criteria of the Berlin definition (ARDS Definition Task Force, 2012). However, of interest, at least a subset of COVID-19 pneumonia patients have preserved lung compliance and present with “silent hypoxaemia”. An L-phenotype has been proposed by Gatinoni and colleagues in an interesting article that stimulates thought and suggests a framework for how to manage COVID-19 patients (Gattinoni et al, 2020). However, there are few patient data, and certainly no experimental evidence, to support this model and the proposed implications for patient management. Furthermore, some patients with “silent hypoxia” and good lung compliance improve their oxygenation with prone positioning (including when performed awake). This doesn’t quite fit the expected response of the L-phenotype in this model, which implies that L patients should be less prone-responsive. Other reports suggest that patients with COVID-19 respiratory failure exhibit similar gas exchange, respiratory system mechanics, and response to prone ventilation as prior large cohorts of patients with ARDS (Ziehr et al, 2020). It is plausible that, at least in the early stages, COVID-19 patients may have different ventilator requirements to other ARDS patients. However, until there is compelling scientific evidence, standard approaches to ventilation should apply.

Furthermore, the concept of different ARDS phenotypes is not new (Wilson & Calfee, 2020). Approaches to phenotyping include physiological (e.g. stratification by P/F ratio), clinical (e.g. baseline clinical characteristics, time course, and radiographic patterns) and biologic (e.g. inflammatory markers). Calfee and colleagues, using a combined clinical and biologic approach, have previously performed a number of secondary analyses of major ARDS randomised controlled trials that identify two distinct subphenotypes of ARDS, namely the hyperinflammatory and hypoinflammatory subphenotypes (Calfee et al, 2014). Their characteristics are shown in table 1. Furthermore these subphenotypes appear stable over the first 3 days of intensive care; in other words, patients do not switch phenotypes over this time period (Delucchi et al, 2018). While such analyses are primarily hypothesis-generating and require further research, they are based on substantially more robust data than any proposed COVID-19 phenotypes and demonstrate that ARDS has never been a homogeneous entity. It is critical to note, however, that the phenotypes rigorously derived by Calfee and colleagues are not the same as the proposed COVID-19 L/H phenotypes.

Table 1. Features of the hyperinflammatory and hypoinflammatory ARDS phenotypes described by Calfee and colleagues. Sources are identified in the table.

| Characteristic | Hyper- inflammatory phenotype | Hypo- inflammatory phenotype | Source |

| Plasma concentrations of inflammatory biomarkers | Higher | Lower | 1 |

| Vasopressor use | Higher | Lower | |

| Serum bicarbonate | Lower | Higher | |

| Sepsis prevalence | Higher | Lower | |

| Mortality | Higher | Lower | |

| Beneficial PEEP settings | Higher | Lower | |

| Beneficial fluid strategy | More liberal | More conservative | 2 |

| Beneficial response to statins | More likely | Less likely | 3 |

Sources 1: Calfee et al, 2014 (ARMA & ALVEOLI trials); 2: Famous et al, 2017 (FACTT trial); 3: Calfee et al, 2018 (HARP2 trial)

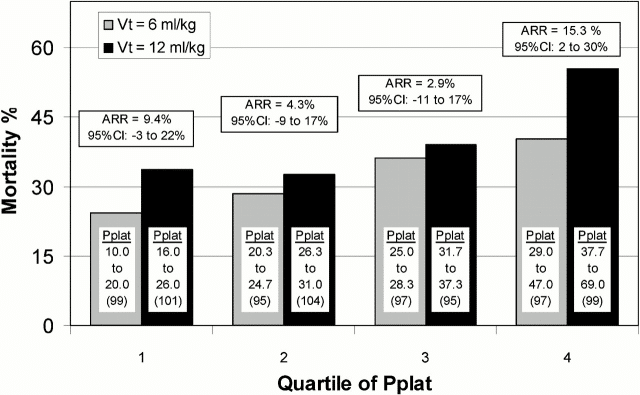

Now, let us return to our understanding of ARDS and consider lung compliance. It is a misconception that ARDS means poor lung compliance. Lung compliance is not part of the 2012 Berlin definition of ARDS (ARDS Definition Task Force, 2012) as it was not found to be helpful, and wasn’t part of the 1994 AECC definition either (Bernard et al, 1994). In the original 1967 description of ARDS by Ashbaugh and colleagues, the 12 patients studied did have poor lung compliance, all being less than 20 mL/cmH20 (Ashbaugh et al, 1967). However, this is a very small sample of patients and in the major ARDS trials that inform the standard management of ARDS, ARDS patients typically have lung compliances that vary across a wide spectrum. For instance, analysis of data from the landmark ARDSNet ARMA trial (ARDSNet, 2000) shows that a quarter of the ARDS patients randomised to 6 mL/kg PBW tidal volumes had plateau pressures in the 10 to 20 cmH20 range, consistent with high lung compliance (Hager et al, 2005) (see Figure 1). Concerningly, this study also found no clear “cut off” suggesting a safe plateau pressure. Instead, the higher the plateau pressure measured, the higher mortality, which has implications for allowing high tidal volumes in ARDS/ COVID-19 patients.

On the other hand, one of the explanations for the mortality benefit of protective lung ventilation in the ARDSNet ARMA trial (ARDSNet, 2000) is the phenomenon of practice misalignment, which occurs when randomization disrupts the normal relationship between clinically important characteristics and therapy titration (Deans et al, 2010). This re-analysis showed that in patients with more compliant lungs (compliance > 0.6 mL/cm H2O/kg PBW), decreasing tidal volume increased mortality compared to increasing tidal volume (37% vs. 21%), despite the overall study finding of a mortality benefit from low tidal volumes (Deans et al, 2010). Our conclusion is that higher tidal volumes in ARDS patients with high lung compliance are probably not (very) harmful. The problem is that lung compliance can change (e.g. through progression of disease) and then harm is likely from high tidal volumes and ventilator induced lung injury (VILI), or even – though controversial – patient self-inflicted lung injury (P-SILI). At the same time, there is no trivial way to prevent P-SILI if it exists; all strategies involve changes in sedation and prolonged neuromuscular blockade that themselves have risks.

Another group of patients with higher lung compliance are mechanically ventilated patients that do not have ARDS. Protective ventilation with lower tidal volumes has been associated with better clinical outcomes for patients without ARDS in systematic reviews (Serpa Neto et al, 2012). More recently though, the PREVENT trial found no benefit of 6 mL/kg PBW tidal volumes compared with 9 mL/kg PBW tidal volumes in critically ill non-ARDS patients, although there was no signal of harm either (Writing Group for the PReVENT Investigators et al, 2018).

Once again, this brings us back to the need for highly trained, experienced, clinicians involved in bedside care. Care should be standardised where possible, but always optimised to the patient actually in the bed. We think the ARDSNet protective lung ventilation approach (ARDSNET, 2000) is a useful starting point for the management of any mechanically ventilated ARDS patient, including patients with COVID-19, especially when expert clinicians are not available to optimise ventilation further. It is unlikely to harm patients, and is more likely to provide benefit. However, when patients are “straying from the path” – and if they are critically ill, they almost always will – they need experts to monitor plateau pressures, static compliance, driving pressures, positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP), hemodynamic responses, sedation scores, and so on, to optimise the interventions being provided.

Figure 1. Mortality difference by quartile of Day 1 Pplat for patients in the ARDSNet ARMA trial (Hager et al, 2005). The range of Pplat levels in cmH20 and the number of patients (n) is detailed in each bar of the graph. ARR = absolute risk reduction; CI = confidence interval. Source: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2718413/

Next, we will discuss COVID-19: “To PEEP, or not to PEEP”?

Further reading

Please refer to these pages from the LITFL Critical Care Compendium for overviews of the key concepts discussed in this blogpost:

- Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS)

- Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Definitions

- ARDSnet Ventilation Strategy

- Coronavirus 2019 disease (COVID-19)

- High airway and alveolar pressures

- Protective Lung Ventilation

- Pulmonary mechanics

- Spontaneous breathing, assisted ventilation, and patient self-inflicted lung injury (P-SILI)

- Ventilator Associated Lung Injury (VALI)

COVID-19: Keeping the baby in the bath series

- COVID-19: Keeping the baby in the bath (Introduction)

- “Silent hypoxaemia” and COVID-19 intubation

- Is COVID-19 ARDS? What about lung compliance?

- COVID-19: “To PEEP, or not to PEEP”?

- MacGyverism and “hacking COVID-19”

- Novel drug therapies and COVID-19 clinical trials

- Overcoming uncertainty in the Age of COVID-19

References

- ARDS Definition Task Force, Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, Fan E, Camporota L, Slutsky AS. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012 Jun 20;307(23):2526-33.

- ARDSNet. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. N Engl J Med. 2000 May 4;342(18):1301-8.

- Ashbaugh DG, Bigelow DB, Petty TL, Levine BE. Acute respiratory distress in adults. Lancet. 1967;2(7511):319–323. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(67)90168-7

- Baldwin J, Cox J. Treating Dyspnea: Is Oxygen Therapy the Best Option for All Patients?. Med Clin North Am. 2016;100(5):1123–1130. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2016.04.018

- Barton LM, Duval EJ, Stroberg E, Ghosh S, Mukhopadhyay S. COVID-19 Autopsies, Oklahoma, USA [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 10]. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;aqaa062. doi:10.1093/ajcp/aqaa062

- Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, et al. The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS. Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149(3 Pt 1):818–824. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.7509706

- Bong CL, Brasher C, Chikumba E, McDougall R, Mellin-Olsen J, Enright A. The COVID-19 Pandemic: Effects on Low and Middle-Income Countries [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 1]. Anesth Analg. 2020;10.1213/ANE.0000000000004846. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000004846

- Borba MGS, Val FFA, Sampaio VS, et al. Effect of High vs Low Doses of Chloroquine Diphosphate as Adjunctive Therapy for Patients Hospitalized With Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Infection: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(4):e208857. Published 2020 Apr 1. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8857

- Brazil V. Translational simulation: not ‘where?’ but ‘why?’ A functional view of in situ simulation. Adv Simul (Lond). 2017;2:20. Published 2017 Oct 19. doi:10.1186/s41077-017-0052-3

- Briel M, Meade M, Mercat A, et al. Higher vs lower positive end-expiratory pressure in patients with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010 Mar 3;303(9):865-73.

- Bromiley M. The journey of human factors in healthcare. J Perioper Pract. 2014;24(3):35–36. doi:10.1177/175045891602400301

- Brewster DJ, Chrimes NC, Do TBT, et al. Consensus statement: Safe Airway Society principles of airway management and tracheal intubation specific to the COVID-19 adult patient group. MJA. {Updated 1 April 2020]. Available at URL: https://www.mja.com.au/system/files/2020-04/Preprint%20Brewster%20updated%201%20April%202020.pdf

- Burke D. Coronavirus preys on what terrifies us: dying alone. CNN, 29 March 2020. Accessed 25 April 2020. Available at URL: https://edition.cnn.com/2020/03/29/world/funerals-dying-alone-coronavirus/index.html

- Calfee CS, Delucchi K, Parsons PE, et al. Subphenotypes in acute respiratory distress syndrome: latent class analysis of data from two randomised controlled trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(8):611–620. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70097-9

- Calfee CS, Delucchi KL, Sinha P, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome subphenotypes and differential response to simvastatin: secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(9):691–698. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30177-2

- Carroll JS, Rudolph JW. 2006. Design of high reliability organizations in healthcare. Qual Saf Health Care. 15:i4–i9.

- Chapin JC, Downs JB, Douglas ME, Murphy EJ, Ruiz BC. Lung expansion, airway pressure transmission, and positive end-expiratory pressure. Arch Surg. 1979;114(10):1193–1197. doi:10.1001/archsurg.1979.01370340099017

- Colman N, Doughty C, Arnold J, et al. Simulation-based clinical systems testing for healthcare spaces: from intake through implementation. Adv Simul (Lond). 2019;4:19. Published 2019 Aug 2. doi:10.1186/s41077-019-0108-7

- Cooper DJ, Rosenfeld JV, Murray L, et al. Decompressive craniectomy in diffuse traumatic brain injury [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2011 Nov 24;365(21):2040]. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(16):1493–1502. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1102077

- Çoruh B, Luks AM. Positive end-expiratory pressure. When more may not be better. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(8):1327–1331. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201404-151CC.

- Deans KJ, Minneci PC, Danner RL, Eichacker PQ, Natanson C. Practice misalignments in randomized controlled trials: Identification, impact, and potential solutions. Anesth Analg. 2010 Aug;111(2):444-50.

- De Jong A, Rolle A, Molinari N, et al. Cardiac Arrest and Mortality Related to Intubation Procedure in Critically Ill Adult Patients: A Multicenter Cohort Study. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(4):532–539. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000002925

- Delucchi K, Famous KR, Ware LB, et al. Stability of ARDS subphenotypes over time in two randomised controlled trials. Thorax. 2018;73(5):439–445. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-211090

- Dul J, Bruder R, Buckle P, Carayon P, Falzon P, Marras WS, Wilson JR, Van der Doelen B. 2012. A strategy for human factors/ergonomics: developing the discipline and profession. Ergonomics. 55:377–395.

- Duggan LV, Marshall SD, Scott J, Brindley PG, Grocott HP. The MacGyver bias and attraction of homemade devices in healthcare. Can J Anaesth. 2019;66(7):757–761. doi:10.1007/s12630-019-01361-4

- Erlandsson K, Odenstedt H, Lundin S, Stenqvist O. Positive end-expiratory pressure optimization using electric impedance tomography in morbidly obese patients during laparoscopic gastric bypass surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2006;50(7):833–839. doi:10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.01079.x

- Famous KR, Delucchi K, Ware LB, et al. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Subphenotypes Respond Differently to Randomized Fluid Management Strategy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(3):331–338. doi:10.1164/rccm.201603-0645OC

- Ferner RE, Aronson JK. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in covid-19. BMJ 2020;369:m1432

- Fujii T, Luethi N, Young PJ, et al. Effect of Vitamin C, Hydrocortisone, and Thiamine vs Hydrocortisone Alone on Time Alive and Free of Vasopressor Support Among Patients With Septic Shock: The VITAMINS Randomized Clinical Trial [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jan 17]. JAMA. 2020;323(5):423–431. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.22176

- Gattinoni L. et al. COVID-19 pneumonia: different respiratory treatment for different phenotypes? (2020) Intensive Care Medicine; DOI: 10.1007/s00134-020-06033-2

- Grein J, Ohmagari N, Shin D, et al. Compassionate Use of Remdesivir for Patients with Severe Covid-19 [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 10]. N Engl J Med. 2020;NEJMoa2007016. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2007016

- Gurses AP, Ozok AA, Pronovost PJ. Time to accelerate integration of human factors and ergonomics in patient safety. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(4):347–351. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000421

- Hager DN, Krishnan JA, Hayden DL, Brower RG; ARDS Clinical Trials Network. Tidal volume reduction in patients with acute lung injury when plateau pressures are not high. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(10):1241–1245. doi:10.1164/rccm.200501-048CP

- Jardin F, Farcot JC, Boisante L, Curien N, Margairaz A, Bourdarias JP. Influence of positive end-expiratory pressure on left ventricular performance. N Engl J Med 1981;304:387–392.

- Jardin F, Genevray B, Brun-Ney D, Bourdarias JP. Influence of lung and chest wall compliances on transmission of airway pressure to the pleural space in critically ill patients. Chest. 1985;88(5):653–658. doi:10.1378/chest.88.5.653

- Kane-Gill SL, Kirisci L, Verrico MM, Rothschild JM. Analysis of risk factors for adverse drug events in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(3):823–8

- Lang M, Som A, Mendoza DP, et al. Hypoxaemia related to COVID-19: vascular and perfusion abnormalities on dual-energy CT [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 30]. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;S1473-3099(20)30367-4. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30367-4

- Leff B, Finucane TE. Gizmo idolatry. JAMA. 2008 Apr 16;299(15):1830-2.

- Levitan R. The Infection That’s Silently Killing Cornoavirus Patients. New York Times. 20 April 2020. [Accessed 26 April 2020]. Available at URL: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/20/opinion/coronavirus-testing-pneumonia.html

- López A, Lorente JA, Steingrub J, et al. Multiple-center, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor 546C88: effect on survival in patients with septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(1):21–30. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000105581.01815.C6

- Magro C, Mulvey JJ, Berlin D, et al. Complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 infection: a report of five cases [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 15]. Transl Res. 2020;S1931-5244(20)30070-0. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2020.04.007

- Maitland K, Kiguli S, Opoka RO, et al. Mortality after fluid bolus in African children with severe infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(26):2483–2495. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1101549

- Mao X, Jia P, Zhang L, Zhao P, Chen Y, Zhang M. An Evaluation of the Effects of Human Factors and Ergonomics on Health Care and Patient Safety Practices: A Systematic Review. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129948. Published 2015 Jun 12. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0129948

- Meng L, Qiu H, Wan L, et al. Intubation and Ventilation amid the COVID-19 Outbreak: Wuhan’s Experience [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 26]. Anesthesiology. 2020;10.1097/ALN.0000000000003296. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000003296

- Mort TC. The incidence and risk factors for cardiac arrest during emergency tracheal intubation: a justification for incorporating the ASA Guidelines in the remote location. J Clin Anesth. 2004;16(7):508–516. doi:10.1016/j.jclinane.2004.01.007

- Nestler C, Simon P, Petroff D, et al. Individualized positive end-expiratory pressure in obese patients during general anaesthesia: a randomized controlled clinical trial using electrical impedance tomography. Br J Anaesth. 2017;119(6):1194–1205. doi:10.1093/bja/aex192

- Nieman GF, Satalin J, Andrews P, Aiash H, Habashi NM, Gatto LA. Personalizing mechanical ventilation according to physiologic parameters to stabilize alveoli and minimize ventilator induced lung injury (VILI). Intensive Care Med Exp. 2017;5(1):8. doi:10.1186/s40635-017-0121-x

- NICE-SUGAR Study Investigators, Finfer S, Chittock DR, et al. Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(13):1283–1297. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0810625

- Nir R. Coronavirus: could government face legal questions over the death of NHS workers during PPE shortage?. The Conversation. April 23, 2020. Accessed 25 April 2020. Available at URL: https://theconversation.com/coronavirus-could-government-face-legal-questions-over-the-death-of-nhs-workers-during-ppe-shortage-137020

- Niven AS, Herasevich S, Pickering BW, Gajic O. The Future of Critical Care Lies in Quality Improvement and Education. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019;16(6):649–656. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201812-847IP

- Onakpoya IJ, Heneghan CJ, Aronson JK. Post-marketing withdrawal of 462 medicinal products because of adverse drug reactions: a systematic review of the world literature [published correction appears in BMC Med. 2019 Mar 2;17(1):56]. BMC Med. 2016;14:10. Published 2016 Feb 4. doi:10.1186/s12916-016-0553-2

- Patterson MD, Geis GL, Falcone RA, LeMaster T, Wears RL. In situ simulation: detection of safety threats and teamwork training in a high risk emergency department. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(6):468–477. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000942

- Petrosoniak A, Hicks C, Barratt L, et al. Design Thinking-Informed Simulation: An Innovative Framework to Test, Evaluate, and Modify New Clinical Infrastructure [published online ahead of print, 2020 Feb 28]. Simul Healthc. 2020;10.1097/SIH.0000000000000408. doi:10.1097/SIH.0000000000000408

- Pirrone M, Fisher D, Chipman D, et al. Recruitment Maneuvers and Positive End-Expiratory Pressure Titration in Morbidly Obese ICU Patients. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(2):300–307. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000001387

- Rice TW, Janz DR. In Defense of Evidence-Based Medicine for the Treatment of COVID-19 ARDS [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 22]. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;10.1513/AnnalsATS.202004-325IP. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202004-325IP

- Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting Characteristics, Comorbidities, and Outcomes Among 5700 Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19 in the New York City Area [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 22]. JAMA. 2020;10.1001/jama.2020.6775. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6775

- Schmidt GA. Counterpoint: should positive end-expiratory pressure in patients with ARDS be set based on oxygenation? No. Chest. 2012;141(6):1382–1384. doi:10.1378/chest.12-0157

- Serpa Neto A, Cardoso SO, Manetta JA, Pereira VG, Espósito DC, Pasqualucci Mde O, Damasceno MC, Schultz MJ. Association between use of lung-protective ventilation with lower tidal volumes and clinical outcomes among patients without acute respiratory distress syndrome: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2012 Oct 24;308(16):1651-9.

- Sutherasan, Y., Vargas, M. & Pelosi, P. Protective mechanical ventilation in the non-injured lung: review and meta-analysis. Crit Care 18, 211 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc13778

- Thille AW, Richard JC, Maggiore SM, Ranieri VM, Brochard L. Alveolar recruitment in pulmonary and extrapulmonary acute respiratory distress syndrome: comparison using pressure-volume curve or static compliance. Anesthesiology. 2007;106(2):212–217. doi:10.1097/00000542-200702000-00007

- Thille AW, Esteban A, Fernández-Segoviano P, Rodriguez JM, Aramburu JA, Peñuelas O, Cortés-Puch I, Cardinal-Fernández P, Lorente JA, Frutos-Vivar F. Comparison of the Berlin definition for acute respiratory distress syndrome with autopsy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013 Apr 1;187(7):761-7.

- Thimbleby H. Technology and the future of healthcare. J Public Health Res. 2013;2(3):e28.

- Tian S, Xiong Y, Liu H, et al. Pathological study of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) through postmortem core biopsies [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 14]. Mod Pathol. 2020;10.1038/s41379-020-0536-x. doi:10.1038/s41379-020-0536-x

- Tobin MJ. Basing Respiratory Management of Coronavirus on Physiological Principles [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 13]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;10.1164/rccm.202004-1076ED. doi:10.1164/rccm.202004-1076ED

- Tremblay L, Valenza F, Ribeiro SP, Li J, Slutsky AS. Injurious ventilatory strategies increase cytokines and c-fos m-RNA expression in an isolated rat lung model. J Clin Invest. 1997;99(5):944–952. doi:10.1172/JCI119259

- Wang M, Cao R, Zhang L, et al. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30(3):269–271. doi:10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0

- Wilson JG, Calfee CS. ARDS Subphenotypes: Understanding a Heterogeneous Syndrome. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):102. Published 2020 Mar 24. doi:10.1186/s13054-020-2778-x

- Writing Group for the PReVENT Investigators, Simonis FD, Serpa Neto A, et al. Effect of a Low vs Intermediate Tidal Volume Strategy on Ventilator-Free Days in Intensive Care Unit Patients Without ARDS: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2018;320(18):1872–1880. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.14280

- Xie A, Carayon P. A systematic review of human factors and ergonomics (HFE)-based healthcare system redesign for quality of care and patient safety. Ergonomics. 2015;58(1):33–49. doi:10.1080/00140139.2014.959070

- Xie J, Tong Z, Guan X, Du B, Qiu H, Slutsky AS. Critical care crisis and some recommendations during the COVID-19 epidemic in China [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 2]. Intensive Care Med. 2020;1–4. doi:10.1007/s00134-020-05979-7

- Ziehr DR, Alladina J, Petri CR, et al. Respiratory Pathophysiology of Mechanically Ventilated Patients with COVID-19: A Cohort Study [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 29]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;10.1164/rccm.202004-1163LE. doi:10.1164/rccm.202004-1163LE

- Zochios V, Parhar K, Tunnicliffe W, Roscoe A, Gao F. The Right Ventricle in ARDS. Chest. 2017;152(1):181‐193. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2017.02.019

- Zuo MZ, Huang YG, Ma WH, Xue ZG, Zhang JQ, Gong YH, Che L. Chinese Society of Anesthesiology Task Force on Airway Management: Expert recommendations for tracheal intubation in critically ill patients with novel coronavirus disease 2019. Chin Med Sci J 2020. [Epub ahead of print].DOI: 10.24920/003724

Chris is an Intensivist and ECMO specialist at The Alfred ICU, where he is Deputy Director (Education). He is a Clinical Adjunct Associate Professor at Monash University, the Lead for the Clinician Educator Incubator programme, and a CICM First Part Examiner.

He is an internationally recognised Clinician Educator with a passion for helping clinicians learn and for improving the clinical performance of individuals and collectives. He was one of the founders of the FOAM movement (Free Open-Access Medical education) has been recognised for his contributions to education with awards from ANZICS, ANZAHPE, and ACEM.

His one great achievement is being the father of three amazing children.

On Bluesky, he is @precordialthump.bsky.social and on the site that Elon has screwed up, he is @precordialthump.

| INTENSIVE | RAGE | Resuscitology | SMACC

Critical care physician and health services researcher bringing the tools of social science and outcomes research to improve the care of patients with critical illnesses. I practice as an intensivist at the University of Michigan’s and the Ann Arbor VA's Critical Care Medicine units, where we work to bring the latest science and the best of clinical practice to patients | iwashyna-lab | @iwashyna |

Intensivist in Wellington, New Zealand. Started out in ED, but now feels physically ill whenever he steps foot on the front line. Clinical researcher, kite-surfer | @DogICUma |