More Befuddling Pupillary Asymmetry

aka Ophthalmology Befuddler 025

You are examining a 46 year-old man who has presented with a persistent cough.

You note the following:

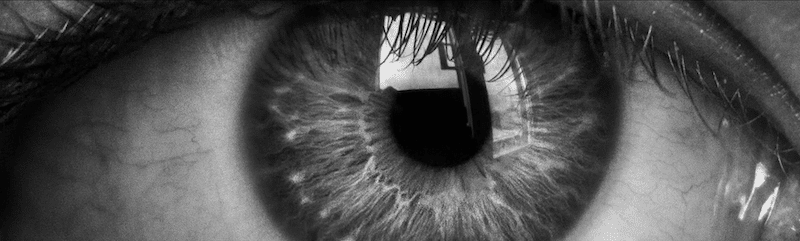

After shining a light in both eyes, you turn off the lights and see this:

Questions

Q1. What is the likely diagnosis?

Answer and interpretation

Described in 1869 by Swiss ophthalmologist, Johann Friedrich Horner (1831 – 1886) was an Swiss ophthalmologist.

Q2. What are the characteristic features of this condition?

Answer and interpretation

The features of Horner’s syndrome include:

- Mild ptosis: paresis of Müller muscle (absent on upward gaze due to intact CN3 function)

- Miosis: paralysis of pupillary dilator muscle

- Ipsilateral anhidrosis

- Apparent enophthalmos

- Heterochromia iridis: may be present in congenital horner’s syndrome

- Lower eyelid reverse ptosis

- The eye may appear slightly bloodshot due to loss of vasoconstrictor activity in the vessels of the bulbar conjunctiva

The features of Horner’s syndrome may be very subtle and can be easily missed:

or they may be obvious:

Q3. What are the possible causes of this condition?

Answer and interpretation

The underlying causes of Horner’s syndrome are numerous and fall into 3 categories – Central, Preganglionic and Postganglionic.

Central lesions (expect anhydrosis of the upper forequarter and coexistent neurological deficits)

- Hemisphere lesions

- hemispherectomymassive infarction of one hemispherethalamic hemorrhagehypothalamic hemorrhage or infarct

- Brainstem lesions

- Vascular events (ischemia or hemorrhage), e.g. Wallenberg syndrome (lateral medullary syndrome)Tumor, e.g. pontine gliomasyringobulbiademyelination, e.g. multiple sclerosisencephalitis

- Neck lesions (central cord lesions)

- syringomyelia (can cause bilateral Horner’s syndrome)

- tumors e.g. ependymoma, glioma

- central cord syndrome due to trauma

- arteriovenous malformation

Preganglionic lesions

- lesions of cervico-thoracic spinal roots

- cervical ribs

- aortic aneurysms

- avulsion of the lower brachial plexus (e.g. Klumpke’s paralysis)

- severe cervical osteoarthritis with impingement from bony spurs (rare)

- AVM

- apical lung disease (some repetition — but a useful category to remember)

- vascular anomalies

- pancoast tumour

- iatrogenic (chest tube, central catheter)

- infection (eg. apical TB)

- cervical sympathetic chain lesions

- local trauma and surgery e.g. thyroidectomy

- tumours

- Apical lung tumor (Pancoast tumor — usually NON squamous cell carcinoma)

- metastases

- thyroid tumours

- neurofibroma

- children — neuroblastoma, lymphoma, metastasis

Postganglionic lesions (may not affect sweating — main sympathetic outflow to facial vessels and sweat glands is from below the superior cervical ganglion)

- Neck lesions affecting the superior cervical ganglion

- tumours — e.g. thyroid

- trauma

- surgery (e.g. tonsillectomy)

- degenerative or inflammatory spinal disease

- Carotid artery lesions

- Spontaneous or traumatic dissection of the carotid artery

- carotid aneurysm

- carotid thrombosis

- pericarotid tumours (e.g. Raeder’s syndrome)

- Base of skull/ carotid canal

- tumor (nasopharyngeal carcinoma)

- trauma

- Headache syndromes

- Cluster headaches

- Migraines

- Middle ear (close proximity to the internal carotid artery, alongside which the sympathetic fibers run)

- infection, e.g. otitis media

- tumor e.g. cholesteatoma

- Cavernous sinus

- tumour, e.g. pituitary tumours such as prolactinoma

- inflammation — Tolosa-Hunt syndrome

- cavernous carotid fistula or aneurysm

- cavernous sinus thrombosis

Q4. What features should be sought on history and examination?

Answer and interpretation

History:

- Is the Horner’s syndrome old or new? (Check old photographs if necessary)

- Associated symptoms: Headaches, arm pain, associated neurological symptoms (e.g. brainstem or spinal lesions), ipsilateral neck pain, symptoms of malignancy

- Past medical history: Previous stroke, head/ neck trauma, surgery (e.g. cardiac, thoracic, thyroid, or neck surgery), headache syndromes

Examination:

- Assess for features of Horner’s syndrome described in Q2.

- Neurological examination: including checking for a hoarse voice and evidence of a lateral medullary syndrome e.g. T1 weakness, brainstem, spinal or brachial plexus lesions

- Neck exam: e.g. supraclavicular lymph nodes, neck masses, carotid bruits, surgical scars

- Other: guided by history and other findings, e.g. clubbing, respiratory exam, detailed eye examination

Q5. Is anisocoria greater in the light or in the dark in this condition?

Answer and interpretation

Anisocoria is greater in a dark room in patients with Horner’s syndrome, as there is good reaction light in both eyes and a dilation lag in the affected pupil.

Q6. How is this condition distinguished from physiological anisocoria?

Answer and interpretation

Check for:

- dilation lag — this is typically present in Horner’s Syndrome but not physiological anisocoria. The degree of anisocoria in the dark is greater after 5 seconds than after 15 seconds of darkness — this is demonstrable in about half of Horner’s syndrome cases. Other factors such as drowsiness may cause miosis in the normal eye and may obscure the dilation lag.

- response to 10% cocaine — dilatation occurs in physiological anisocoria but not with Horner’s syndrome. Cocaine exerts its effects by blocking noradrenaline reuptake, and has no effect on a sympathetically denervated pupil because no noradrenaline is released. Re-examine the eyes an hour after administering 2 drops of 10% cocaine to each eye — a post-cocaine anisocoria amplitude difference of > 0.8mm has >1000:1 odds of being due to a Horner’s syndrome. (Use topical anesthestic drops first — cocaine in the eye can really sting!)

According to Jeff Mann’s EM Guidemap on Anisocoria (no longer online, sadly), the features of physiological anisocoria are:

- always less than 1.0 mm difference, and usually <0.5 mm difference, in size between the pupils

(the amplitude of the difference may or may not vary greatly under dim or bright light conditions, but may vary in amplitude from hour-to-hour) - pupillary constriction is normal to light and during near vision

- both pupils respond equally promptly to direct light, and the smaller pupil usually still dilates equally promptly in the dark

- occasionally the anisocoria may switch sides (called “alternating” or “seesaw” anisocoria)

Q7. How can central/ preganglionic causes be distinguished from postganglionic causes of this condition?

Answer and interpretation

Once the diagnosis of Horner’s syndrome is confirmed, the hydroxyamphetamine test can be performed to distinguish between postganglionic and central/ preganglionic causes of Horner’s syndrome. Hydroxyamphetamine causes noradrenaline release from sympathetic neurons.

Dilatation with 1% hydroxyamphetamine only occurs in Horner’s syndrome with a central or preganglionic cause because the postganglionic nerves can still release noradrenaline. Dilatation does not occur if the cause is postganglionic, as noradrenaline stores are depleted.

This tests needs to be done >24-72 hours after the 10% cocaine test for it to work — it can be performed by an ophthalmologist during inpatient or outpatient follow up

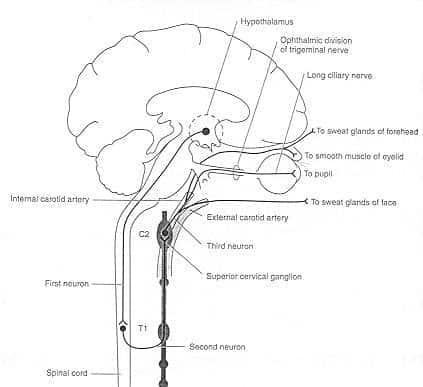

Q8. Describe the oculosympathetic pathway.

Answer and interpretation

Understanding the oculosympathetic pathway helps us understand why Horner’s syndrome occurs, and provides a framework for considering the underlying causes. The pathway consists of a three-neuron arc.

First-order neurons

- originate in the posterior hypothalamus

- descend to the intermediolateral gray column of the spinal cord

- synapse at the ciliospinal center of Budge at spinal levels C8 to T2.

Preganglionic second-order neurons

- arise from the intermediolateral column

- leave the spinal cord by the ventral spinal roots

- enter the rami communicans and join the paravertebral cervical sympathetic chain

- ascend through this chain to synapse at the superior cervical ganglion.

Postganglionic third-order neurons

- originate in the superior cervical ganglion

- enter the cranium with the internal carotid artery

- joins the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve (V1) within the cavernous sinus

- reach the ciliary muscle and pupillary dilator muscle via the nasociliary nerve and the long ciliary nerves

And don’t forget about the other structures that are related to the cavernous sinus:

Q9. What factors affect the size of the affected pupil in this condition?

Answer and interpretation

The degree of miosis depends on the following:

- the resting size of the pupils

- the completeness of the injury

- the extent of reinnervation of the pupillary dilator muscle

- the degree of denervation supersensitivity

- the concentration of circulating adrenergic agents in the blood e.g. an anxious state causes greater dilatation of the normal pupil and anisocoria is more obvious

- the alertness of the patient. e.g. a fatigued or drowsy patient has diminished sympathetic outflow from the hypothalamus causing less dilatation of the normal pupil and anisocoria is less obvious.

Q10. What investigations are required in a patient with this condition?

Answer and interpretation

Generally, a longstanding Horner’s syndrome is likely to be benign. If the findings are new, a more detailed work up is required. Most, but not all postganglionic causes are relatively harmless. Some authorities advise imaging of the entire oculosympathetic chain in all cases of new-onset Horner’s syndrome if there are no clues as to the etiology. It is usually wise to at least get a chest x-ray prior to discharge from the ED in patients who are going to be followed up as outpatients.

Useful investigations may include:

- Laboratory — FBC, inflammatory markers, lymph node biopsy

- Imaging — chest XR, CT chest, CTA/MRA of head/neck, carotid doppler ultrasound, carotid angiography

Q11. What conditions should be suspected in the case of this ocular finding and:

…the following clinical manifestations

ipsilateral headache and contralateral hemispheric neurological deficits

…show answer

Carotid dissection — this must be excluded

cranial nerve III, V1, V2 and/or VI lesions

…show answer

suspect cavernous sinus pathology (V3 is not affected) — e.g. cavernous sinus thrombosis, carotid cavernous fistula, tumours, Tolosa-Hunt syndrome

cranial nerve III, V1, and/or VI lesions

…show answer

suspect superior orbital fissure pathology (V2 and V3 are not affected)

cranial nerve II, III, IV, V1, and/or VI lesions

…show answer

suspect superior orbital apex pathology (V2 and V3 are not affected)

a cranial nerve II lesion and an incomplete cranial nerve III dysfunction

…show answer

suspect posterior orbital pathology (IV, V, and VI are are not affected)

brainstem signs and an affected pupil that does not respond to the 10% cocaine test

…show answer

central Horner syndrome due to a brainstem lesion, e.g. stroke or hemorrhage, Wallenberg syndrome

sensory and motor abnormalities of the limbs, no brainstem signs, and an affected pupil that does not respond to the 10% cocaine test

…show answer

central Horner’s syndrome due to cervical spinal cord pathology

a hoarse voice

…show answer

a compressive lesion in the chest or neck affecting the preganglionic fibers (second neuron lesion) and the recurrent laryngeal nerve

a hoarse voice, ipsilateral palatal weakness, shortness of breath with a high diaphragm on the ipsilateral side of the chest XR

…show answer

a compressive lesion (tumor) behind the carotid sheath at the C6 level affecting the preganglionic (second neuron) fibers, as well as the phrenic, vagus and recurrent laryngeal nerves.

…and finally

And finally a video summary…

To learn more about how to interpret this ocular finding in the context of brainstem lesions read the Brainstem Rules of 4 and test yourself on some Brainstem Lesions, and then some More brainstem lesions.

References

- Ehlers JP, Shah CP, Fenton GL, Hoskins EN. The Wills Eye Manual: Office and Emergency Room Diagnosis and Treatment of Eye Disease Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

- NSW Statewide Opthalmology Service. Eye Emergency Manual — An illustrated Guide. [Free PDF]

OPHTHALMOLOGY BEFUDDLER

Chris is an Intensivist and ECMO specialist at The Alfred ICU, where he is Deputy Director (Education). He is a Clinical Adjunct Associate Professor at Monash University, the Lead for the Clinician Educator Incubator programme, and a CICM First Part Examiner.

He is an internationally recognised Clinician Educator with a passion for helping clinicians learn and for improving the clinical performance of individuals and collectives. He was one of the founders of the FOAM movement (Free Open-Access Medical education) has been recognised for his contributions to education with awards from ANZICS, ANZAHPE, and ACEM.

His one great achievement is being the father of three amazing children.

On Bluesky, he is @precordialthump.bsky.social and on the site that Elon has screwed up, he is @precordialthump.

| INTENSIVE | RAGE | Resuscitology | SMACC