Abdominal Trauma: Blunt or penetrating

Reviewed and revised 21 December 2015

OVERVIEW

Assessment of abdominal trauma requires the identification of immediately life-threatening injuries on primary survey, and delayed life threats on secondary survey.

- Primary survey

- Resuscitation

- Secondary survey

- Diagnostic evaluation

- Definitive care

Abdominal trauma is classified as blunt or penetrating, assessment and management is modified accordingly

BLUNT ABDOMINAL INJURY

Blunt abdominal injuries often managed conservatively, though interventional radiology and surgery are indicated for severe injuries

- Common mechanisms include road traffic crashes, falls, sports injuries and assaults

- organs most affected are : spleen > liver > small and large intestine

PENETRATING ABDOMINAL INJURY

Most patients with significant penetrating injury require laparotomy; there are differences in the management of projectiles (e.g. gunshot wounds) and non-projectiles (e.g. stabbings)

- Any wound between the nipple line (T4) and the groin creases anteriorly, and from T4 to the curves of the iliac crests posteriorly is potentially a penetrating abdominal injury

- If the wound was caused by a projectile, then a penetrating abdominal injury could result from an entry wound in almost any part of the body

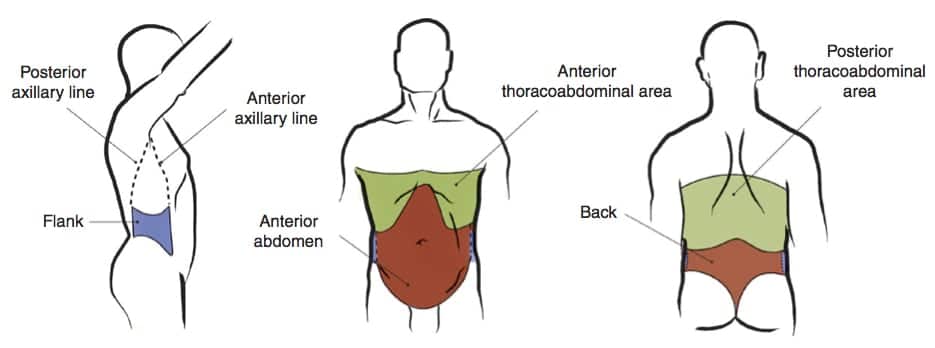

These are the 4 regions of the abdomen to consider in penetrating injury:

- Anterior abdomen

— Between the anterior axillary lines; bound by the costal margin superiorly and the groin crease distally. - Thoracoabdominal area

- — The area superiorly delimited by the fourth intercostal space (anterior), sixth intercostal space (lateral), and eighth intercostal space (posterior), and inferiorly delimited by the costal margin (definitions vary — a pragmatic approach is to use the nipple line as the upper boundary… in non-obese men at least!). Injuries in the region increase the likelihood of chest, mediastinal, and diaphragmatic injuries.

- Flanks

— From the inferior costal margin superiorly to the iliac crests; bound anteriorly by the anterior axillary line and posteriorly by the posterior axillary line. - Back

— Between the posterior axillary lines extending from the costal margin to the iliac crests.

ASSESSMENT OF BLUNT ABDOMINAL TRAUMA

Primary survey

- Use a coordinated team-based systematic approach aimed at identifying, prioritising and treating immediate and delayed life-threats

- Abdominal and pelvic injuries may cause life-threatening hemorrhage

- Initial examination of the abdomen is best performed in the ‘C’ phase of the primary survey, with the mindset of ‘Find the bleeding, stop the bleeding’

- 2 x 16G cannula

- activation of massive transfusion protocol if needed

Secondary survey (search for signs that indicate need for emergency laparotomy)

- Inspection

- abrasions

- bruising

- seat belt

- lap belt: 30% chance of mesenteric or intestinal injury

- retroperitoneal haemorrhage: ecchymosis of the peri-umbilical area (Cullen’s sign) and the flanks (Grey-Turner’s sign)

- genital and perineum

- Palpation

- fullness: haemorrhage

- crepitation of lower rib cage: hepatic or splenic injury

- peritonism: ruptured viscus with leakage

- rectal or vaginal examination

Investigations

- Trauma series (e.g. CXR, pelvis XR, c-spine XR)

- Trauma blood panel (e.g. FBC, UEC, LFTs, lipase, coags, group and hold, BHCG)

- Imaging (bedside FAST scan, +/- Ct abdomen if haemodynamically stable and imaging warranted)

Insert gastric tube and IDC

IMAGING IN BLUNT ABDOMINAL TRAUMA

In the absence of physical signs that indicate a need for immediate emergency laparotomy, imaging can be used to determine if emergency laparotomy is indicated, and help prioritise, identify and guide the management of other injuries

FAST

- 70-95% sensitivity

- 4 regions:

- subxipoid: pericardial space + rough assessment of contractility and filling

- RUQ

- splenorenal recess

- pelvis

- Pros

- Quick to perform with immediate results

- Repeatable

- Patient doesn’t have to leave Emergency department

- Sensitivity approaching 96% in detecting >800mls blood

- Cons

- Requires >250 mL free fluid to collect in Morison’s pouch for a positive result

- Operator dependent

- Doesn’t specify anatomical structures injured

- Does not distinguish other causes of intraperitioneal fluid (e.g. ascites, residual fluid after DPL, bladder rupture)

- Doesn’t look at solid organs, hollow viscus or retroperitoneal structures

- Can be technically difficult in obese patients, those with lots of bowel gas or if subcutaneous emphysema is present

Diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL)

- DPL is now rarely performed due to the advent of the FAST scan. It’s main role is when FAST and CT are unavailable or in mass casualty situations.

- Procedure:

- mini-laparotomy with placement of lavage catheter (chest drain or Foley) into peritoneal cavity directed towards pelvis

- blood -> positive

- if negative: 1L of warm saline in -> effluent sent for RBC, WCC, food, bile, bacteria

- Pros:

- Highly sensitive for intraperitoneal hemorrhage (>97%)

- Rapid

- Performed at the bedside

- Cons:

- Invasive

- Doesn’t specify anatomical structures injured

- False positives may result from trauma during the procedure (up to 25% negative laparotomy rate)

- Rarely performed, practitioner’s have become deskilled

- Residual fluid following DPL makes subsequent FAST scans unreliable

- Modified technique required if pregnant, pelvic fracture or midline scarring

- The modified procedure of diagnostic peritoneal aspirate (DPA) is useful in the hemodynamically unstable abdominal trauma with a negative FAST scan — a positive DPA indicates a false negative FAST scan and such patients require emergency laparotomy

CT ABDO/PELVIS

- for haemodynamically stable patients

- definitive imaging with multidetector CT Abdo/pelvis is performed in haemodynamically stable when an emergency laparotomy is not indicated and one of the following is present:

- Trauma patients with abdominal tenderness

- Trauma patients with altered sensorium

- Distracting injuries or injuries to adjacent structures

- Pros

- Identifies specific anatomical structures injured, allows grading of severity and helps guide management

- Concurrent imaging of other body compartments is frequently indicated

- Images retroperitoneal structures

- Provides imaging of the thoracolumbar vertebrae and other skeletal structures

- A blush of IV contrast is a strong predictor of failure of non-interventional management

- Cons

- Patient usually has to leave the ED

- Patient transfers are time consuming

- Requires IV contrast and risk adverse reactions

- Radiation exposure

- Less sensitive with pancreatic, diaphragmatic and hollow viscus injuries

- Poor access to patient during the scan should he or she deteriorate

- Requires additional skilled staff (CT radiographers and radiologists)

ASSESSMENT OF PENETRATING ABDOMINAL TRAUMA

In patients with penetrating abdominal injury, if immediate emergency laparotomy is not indicated then once the patient is stabilised we have to answer 2 questions that act as key decision nodes guiding our approach:

- does the wound penetrate the peritoneum?

- is there intraperitoneal organ injury?

Only two-thirds of anterior abdominal stab wounds violate the peritoneum, and only half of these require operative intervention.

Assessment for peritoneal penetration:

- local wound exploration — involvement of abdominal fascia is considered a positive result.

- CXR — peritoneal penetration is confirmed by free air under diaphragm, but absence of free does not rule it out

- Ultrasound —peritoneal penetration is confirmed by free fluid in the abdomen or evidence of abdominal fascia violation, but absence of these findings does not rule it out

- DPL — this is invasive and not specific for injuries requiring operative intervention. It may be use if ultrasound is unavailable and some advocate it for thoracoabdominal wounds. A positive result is >100,000 RBCs/hpf for anterior abdominal wounds, and 10,000 RBCs/hpf for thoracoabdominal wounds that are at higher risk of diaphragmatic injury. Some suggest using the lower threshold for anterior wounds as well, but this leads to a higher negative laparotomy rate.

If the fascia is intact (i.e. all of the above are confirmed negative, excluding peritoneal penetration):

- the wound can be cleaned and closed in the ED

- If there are no other concerns the patient may be discharged

If local wound exploration is in adequate and abdominal fascia injury cannot be excluded, or there is evidence of peritoneal penetration, then further investigation is needed to assess for intraperitoneal injury

IMAGING & INVESTIGATION OF PENETRATING ABDOMINAL INJURIES

Similar to blunt abdominal trauma, a coordinated team-based systematic approach is used with the aim of identifying, prioritising and treating immediate and delayed life-threats

If emergency laparotomy is not indicated, there are two options for identifying intraperitoneal injury:

- CT abdomen

- direct laparoscopy

CT abdomen (97% sensitive for peritoneal violation) is usually performed to look for evidence of peritoneal penetration and intraperitoneal injury:

- free air

- free fluid

- bowel wall thickening

- wound tracts adjacent to a hollow viscus/solid organ injury

An alternative in some centers is direct laparoscopy, which is often performed for left thoracoabdominal wounds due to the risk of diaphragmatic injury (17%) and may allow repair.

If the peritoneum is penetrated, then the options are:

- laparotomy if there is intraperitoneal injury requiring operative repair (e.g. colon perforation), or

- observation with serial examination +/- FAST scans and serial full blood count checks for 24 hours if no intraperitoneal injury

(some injuries such as those the pancreas or a hollow viscus may not be detectable initially and may present later)

The option of selective non-operative management of anterior abdominal wounds is made based on the type of intraperitoneal injury and the experience of the trauma center

GUNSHOT WOUNDS (GSWs)

Assessment and management is modified compared to non-projectile penetrating abdominal trauma (e.g. stab wounds)

- Abdominal gunshot wounds are more likely to penetrate the peritoneum (80%), and those that do are more likely to cause intraperitoneal injury (90%)

- Bullets and similar missiles are higher velocity and may ricochet resulting in unpredictable wound tracts

Differences in assessment:

- Local wound exploration should only be performed if the projectile was low velocity with a presumed tangential tract

- CT abdomen with IV contrast is the optimal method for determining both peritoneal penetration and intraperitoneal injury unless emergency laparotomy is indicated. It also identifies the missile pathway. Triple contrast is used if suspected gastrointestinal injury

- DPL is an alternative for detecting intraperitoneal injury if CT is not available, using a threshold of 5 to 10,000 RBCs/hpf for a positive result

- Direct laparoscopy is also useful for left thoracoabdominal gunshot wounds

Differences in management:

- Traditionally all gunshot wounds with peritoneal penetration undergo laparotomy

- In centers experienced with the management of GSWs selective non-operative management may be used, such as isolated liver injuries (RUQ) and patients who remain hemodynamically stable with no evidence of peritonism

INTERVENTIONAL THERAPY

Common indications for emergency laparotomy are:

- Peritonism

- Free air

- Evisceration

- Penetrating abdominal trauma + hypotension

- Gunshot wound traversing peritoneum or retroperitoneum

- GI bleeding following penetrating trauma

- Penetrating object is still in situ (risk of precipitous haemorrhage on removal)

- Blunt abdominal trauma + hypotension with positive FAST scan, positive diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) or peritonism

Interventional radiology

- main role in abdominal trauma is stop bleeding without the physiological stress of surgery

- sources of bleeding are typically spleen, liver, pelvis, retroperitoneal or gastrointestinal haemorrhage

- techniques include embolisation and balloon occlusion

- in some centers may be performed in conjunction with operative intervention (e.g. Raptor Suite)

Damage control surgery

- Damage control surgery involves limited surgical interventions to control haemorrhage and minimize contamination until the patient has sufficient physiological reserve to undergo definitive interventions

- Damage control surgery, along with permissive hypotension and hemostatic resuscitation, is integral to the concept of damage control resuscitation

- This strategy was derived from military experience and is now increasingly adopted into civilian trauma management

ICU MANAGEMENT

- repeated primary and secondary surveys (high chance of unrecognized injuries)

Admission for Non-operative management of Solid Organ Injury

- serial examination

- serial measurement of laboratory parameters

- often strict bed rest

- optimise coagulation

- if deteriorates: laparotomy or interventional radiology

Admission after Damage Control Surgery

- goal = avoidance of the triad of acidosis, hypothermia and coagulopathy

- correct parameters

- return to surgery for definitive care

- warm: room, blankets, FAW, warm fluids

- acidosis: should correct with restoration of volume and Hb

- coagulopathy: replace Ca2+, appropriate product transfusion

Prevent, seek and treat complications

- sepsis

- venous thromboembolism

- pressure areas

- disability

- death

Supportive care and monitoring (e.g. FASTHUGS IN BED Please)

DUODENAL INJURY

Assessment

- Suspect in unrestrained drivers in frontal impact MVC and in patients who sustain direct blows to the abdomen, e.g. from bicycle handle bars.

- Abdominal pain and tenderness

- Bloody gastric aspirate

- Retroperitioneal air on abdominal x-ray or CT abdomen

- Can be confirmed by double contrast CT abdomen

Management

- Resuscitation

- Surgical repair via laparotomy

SMALL INTESTINAL INJURY

Assessment

- Clinical signs can be minimal initially

- Usually a deceleration injury (e.g. MVC with lap belt)

- May involve bowel wall and / or mesenteric avulsion with subsequent intraperitoneal bleeding and devascularisation of bowel

- Coexistent lumbar distraction fracture (Chance fracture) may be present

- An abdominal seatbelt sign mandates definitive imaging

- May be missed on early FAST scan and CT abdomen — DPL or repeat examination may be required

Management

- Usually requires surgical repair

PANCREATIC INJURY

Assessment

- Classically due to a direct blow, e.g. motorbike handlebars

- Abdominal pain +/- vomiting

- Double contrast CT abdomen and amylase / lipase may initially be normal

Management

- Usually conservative, rarely surgical exploration and repair are needed

OTHER SPECIFIC INJURIES

References and links

LITFL

- Trauma Tribulation 023 — Trauma! Abdominal trauma decision making

- Trauma Tribulation 019 — Trauma! Assessing the Abdomen

- Trauma Tribulation 020 — Trauma! Abdominal injuries

- CCC — Damage Control Surgery

- CCC — The Open Abdomen

- CCC — Interventional radiology and the critically unwell

- CCC — Digital rectal exam (DRE) in trauma

- CCC — Raptor Suite

Journal articles

- Kozar RA, Feliciano DV, Moore EE, Moore FA, Cocanour CS, West MA, Davis JW, McIntyre RC Jr. Western Trauma Association/critical decisions in trauma: operative management of adult blunt hepatic trauma. J Trauma. 2011 Jul;71(1):1-5. PMID: 21818009

- Moore FA, Davis JW, Moore EE Jr, Cocanour CS, West MA, McIntyre RC Jr. Western Trauma Association (WTA) critical decisions in trauma: management of adult blunt splenic trauma. J Trauma. 2008 Nov;65(5):1007-11. PMID: 19001966.

- Raikhlin A, Baerlocher MO, Asch MR, Myers A. Imaging and transcatheter arterial embolization for traumatic splenic injuries: review of the literature. Can J Surg. 2008 Dec;51(6):464-72. PMC2592580.

FOAM and web resources

- Trauma Professional’s Blog — Bucket Handle Injury Part 1 and Part 2

- Trauma Professional’s Blog —Seat Belt Sign

- Trauma Professional’s Blog — Bicycle handlebar injury to the epigastrium

Critical Care

Compendium

Chris is an Intensivist and ECMO specialist at The Alfred ICU, where he is Deputy Director (Education). He is a Clinical Adjunct Associate Professor at Monash University, the Lead for the Clinician Educator Incubator programme, and a CICM First Part Examiner.

He is an internationally recognised Clinician Educator with a passion for helping clinicians learn and for improving the clinical performance of individuals and collectives. He was one of the founders of the FOAM movement (Free Open-Access Medical education) has been recognised for his contributions to education with awards from ANZICS, ANZAHPE, and ACEM.

His one great achievement is being the father of three amazing children.

On Bluesky, he is @precordialthump.bsky.social and on the site that Elon has screwed up, he is @precordialthump.

| INTENSIVE | RAGE | Resuscitology | SMACC