Abdominal CT: bowel perforation

Identifying bowel perforation

Perforation of the gastrointestinal tract can be due to a variety of causes. Patients often present with sudden and severe abdominal pain, peritonitis and laboratory abnormalities.

While you might be able to see free air with an x-ray, it will not provide a specific cause and can easily overlook smaller, localized perforations that have not spread throughout the entire abdomen. CT is the exam of choice to identify the cause of pain, the site of perforation, and direct surgical management.

It is important to consider the different causes of perforation in the gastrointestinal tract. Here are a few of the most common causes to consider:

- Peptic ulcer

- Ischemia

- Obstruction

- Appendicitis

- Diverticulitis

- Trauma

Key findings

The key findings are free intraperitoneal air and peritonitis.

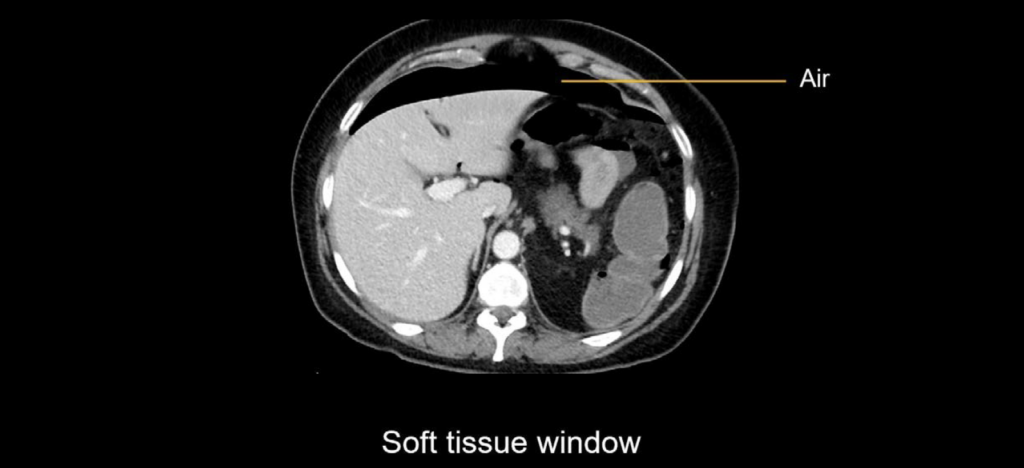

Free intraperitoneal air

Free intraperitoneal air is the first finding that should raise suspicion of a perforation. When there is a large amount of air it can be hard to miss even on soft tissue windows. Below we can see a black pocket in front of the liver.

While seeing a large amount of air confirms a perforation, you still have to determine the cause. Shifting to a bone or lung window will allow you to carefully evaluate the pattern of air if the site of perforation is not evident.

The bone windows are slightly better for being able to see both the solid organs and bowel along with the free air, whereas the stark contrast of the lung windows provides the highest sensitivity for smaller dots of air.

Clinical Case 1

Scroll through these images from a patient presenting with severe abdominal pain.

- Turning on lung windows, you can see that there is a large amount of intraperitoneal air as well as several locules within the intraabdominal fat.

- Switching back to soft tissue windows, take a closer look at the bowel to try to find the source. In the mid abdomen is the distended cecum, a likely source of the perforation.

- Continue to follow the dilated colon to see if you can find the point of obstruction.

- Find the transition point where there is thickening and irregularity.

- Take a closer look at the coronal image, where you can see the dilated descending colon leading into an area of soft tissue thickening. There’s increased enhancement and thickening in this location, with an apple core-like lesion.

The lesion was later confirmed to be an adenocarcinoma causing obstruction, which eventually resulted in perforation of the caecum.

Peritonitis

Peritonitis is another helpful clue for making this diagnosis, particularly for smaller localized perforations that do not distribute air all over the abdominal cavity. This pattern occurs more commonly with perforated diverticulitis or appendicitis

In the example shown next, the patient has thickening and increased enhancement of many small bowel loops, which at first glance might mimic infectious enteritis.

However, in this same case, there is a collection just outside the wall of the sigmoid colon, which is hard to discern on the soft tissue window but looks a lot like stool when using bone window settings. This is perforated diverticulitis with extraluminal stool and peritonitis.

Clinical Case 2

Scroll through these images from a patient presenting with severe abdominal pain.

- There is a lot going on in this case, so let’s use both axial and coronal views to identify the key findings of perforation.

- Keep in mind the value of switching the window to the lung or bone to help see the free air.

- Following the descending colon down to the sigmoid gives you an anatomic anchor point to understand what is going on.

- The sigmoid colon is thickened and has surrounding stranding, and if you look carefully, there is a single thickened and inflamed diverticulum projecting posteriorly.

- From the sigmoid colon, there is a thin tract of air leading to a collection of air and fluid. This is an early abscess as it is not well-defined.

- There is also a larger amount of air elsewhere tracking throughout the abdomen.

- Notice the adjacent small bowel is inflamed, indicating peritonitis.

It might surprise you that the perforated diverticulum is not more impressive than was shown in this case, but it is not uncommon for it to be relatively small as the perforation has an effect of relieving the colonic inflammation, spreading it throughout the rest of the abdomen.

This is an edited excerpt from the Medmastery course Abdominal CT Pathologies by Michael P. Hartung, MD. Acknowledgement and attribution to Medmastery for providing course transcripts

- Hartung MP. Abdominal CT: Common Pathologies. Medmastery

- Hartung MP. Abdominal CT: Essentials. Medmastery

- Hartung MP. Abdomen CT: Trauma. Medmastery

References

- Hartung MP. Abdominal CT: Imaging the small bowel

- Nickson C. Small bowel obstruction DDx. CCC

- Cadogan M. AXR Interpretation. CCC

- Nickson C. Abdominal X-ray and CT. CCC

- Top 100 CT scan quiz. LITFL

Radiology Library: Abdominal CT: Imaging important abdominal structures

- Hartung MP. Abdominal CT: acute appendicitis

- Hartung MP. Abdominal CT: diverticulitis

- Hartung MP. Abdominal CT: small bowel obstruction

- Hartung MP. Abdominal CT: closed loop small bowel obstruction

- Hartung MP. Abdominal CT: enteritis and colitis

- Hartung MP. Abdominal CT: peptic ulcer disease

- Hartung MP. Abdominal CT: peptic ulcer perforation

- Hartung MP. Abdominal CT: bowel perforation

Abdominal CT interpretation

Assistant Professor of Abdominal Imaging and Intervention at the University of Wisconsin Madison School of Medicine and Public Health. Interests include resident and medical student education, incorporating the latest technology for teaching radiology. I am also active as a volunteer teleradiologist for hospitals in Peru and Kenya. | Medmastery | Radiopaedia | Website | Twitter | LinkedIn | Scopus

MBChB (hons), BMedSci - University of Edinburgh. Living the good life in emergency medicine down under. Interested in medical imaging and physiology. Love hiking, cycling and the great outdoors.