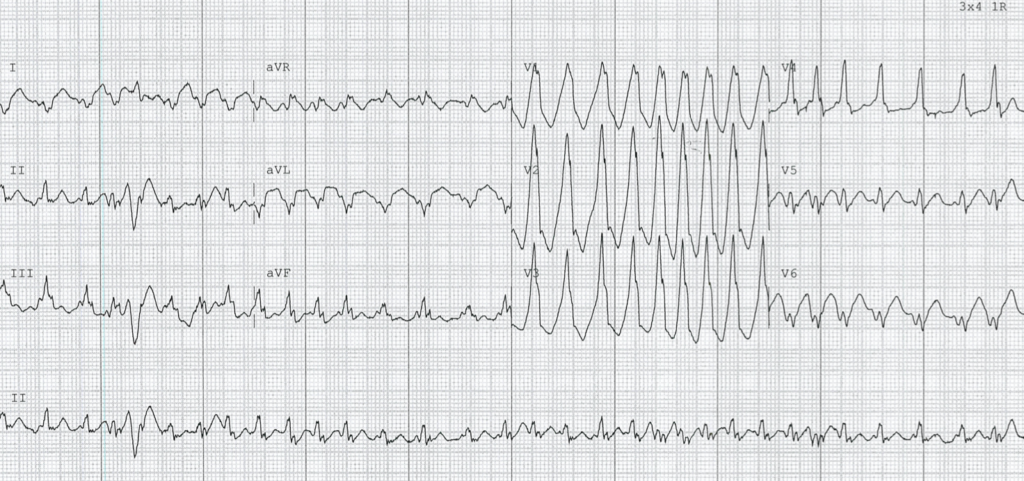

ECG Case 136

A 61-year-old lady is brought in by ambulance with palpitations and dizziness. GCS 15. HR 190, BP 75/50.

Describe and interpret this ECG

ECG ANSWER and INTERPRETATION

- Irregularly irregular broad complex tachycardia, rate ~190 bpm

- Right axis deviation

- P waves difficult to ascertain

- On first glance, QRS morphology in precordial leads may resemble a right bundle branch pattern

- Appropriately discordant ST-segment and T-wave changes

Irregularly irregular rhythm seen here is consistent with atrial fibrillation (AF). Conduction delay may be due to aberrancy (right bundle branch block) or pre-excitation.

However, there are two ECG features that point towards the presence of an accessory pathway (AP) – can you spot them?

Reveal answer

- Extremely rapid ventricular rates – up to 300 bpm in some places. This is too rapid to be conducted via the AV node

- Beat-to-beat variation in QRS morphology

OUTCOME

This patient underwent successful DCCV, with reversion to sinus rhythm and resolution of haemodynamic instability.

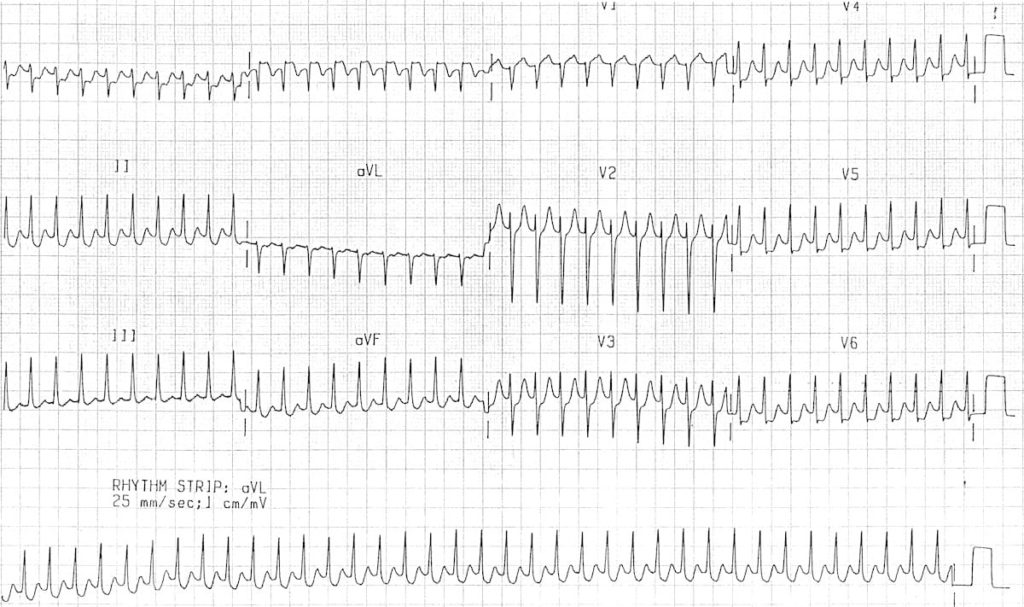

A repeat ECG was taken:

What is your interpretation?

The baseline ECG is consistent with a left lateral AP:

- Sinus rhythm, rate 90 bpm

- Normal P wave axis, persistent right axis deviation

- PR interval is relatively short at ~120ms, and there are broad QRS complexes with a slurred upstroke to the QRS complex – the delta wave

- Dominant R wave in V1 – this is associated with a left-sided AP and is sometimes termed a Type A Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) pattern

- Negative delta wave in aVL simulates the Q waves of lateral infarction – this is known as the “pseudo-infarction pattern”

Tall R waves in right precordial leads can mimic right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH). These changes are due to pre-excitation and do not indicate RVH.

CLINICAL PEARLS

WPW Pattern versus Syndrome

Is there clinical significance?

Traditionally, identification of a short PR interval and a delta wave on the ECG has confirmed the presence of a WPW pattern. The diagnosis of WPW syndrome has only been made when there is a history or subsequent development of an arrhythmia.

However, the clinical utility of these established “separate” definitions is questionable. Even if this patient had no prior history of palpitations or pre-excited AF, we would need to evaluate further and probably ablate their AP.

Management of pre-excitation AF

The emergent management of our patient above is fairly straight forwards. Regardless of the presence of an AP, in a patient with unstable haemodynamics due to (or presumably due to) AF, urgent synchronised DC cardioversion is required. Note the specific wording of this statement – if a patient with chronic AF comes with shock due to haemorrhage, we should not DCCV this patient.

However, it is in the more stable patient that we must be cautioned with the presence of an AP. Treatment with AV nodal blocking drugs (e.g. adenosine, calcium channel blockers, beta blockers) should be avoided for two reasons:

- Most APs have a shorter refractory period than the AV node, hence the ventricular rate can be more rapid if AV conduction occurs preferentially via the AP

- Normally, anterograde conduction occurs via both the AP and AV node, and these wavefronts fuse in the ventricles. Conduction through the AV node is actually a brake on AP conduction, ceasing its propagation path in the ventricle

AV nodal blockade can thus be catastrophic, preferencing conduction via the AP and leading to uninhibited propagation through the ventricles. The result is an increase in ventricular rate and possible degeneration into ventricular tachycardia (VT) or ventricular fibrillation (VF).

The most widely available medical management option in the stable patient is procainamide.

Procainamide: Mechanism of action

- Procainamide is a class I antiarrhythmic that targets the AP

- Prolongs action potential duration in atrial and ventricular myocardium

- No AV nodal blocking effect

- Effective in both reversion, and in slowing ventricular rate

- Safe in children

- Bolus dose followed by infusion

The preferred long-term approach for patients with an AP and recurrent tachyarrhythmias is ablation.

Tachyarrhythmias in WPW

There are only two main forms of tachyarrhythmias that occur in patients with WPW:

- Atrial fibrillation or flutter. Due to direct conduction from atria to ventricles via an AP, bypassing the AV node (as in our patient above)

- Atrioventricular re-entry tachycardia (AVRT). As the name suggests, this is due to formation of a re-entry circuit involving the AP and AV node

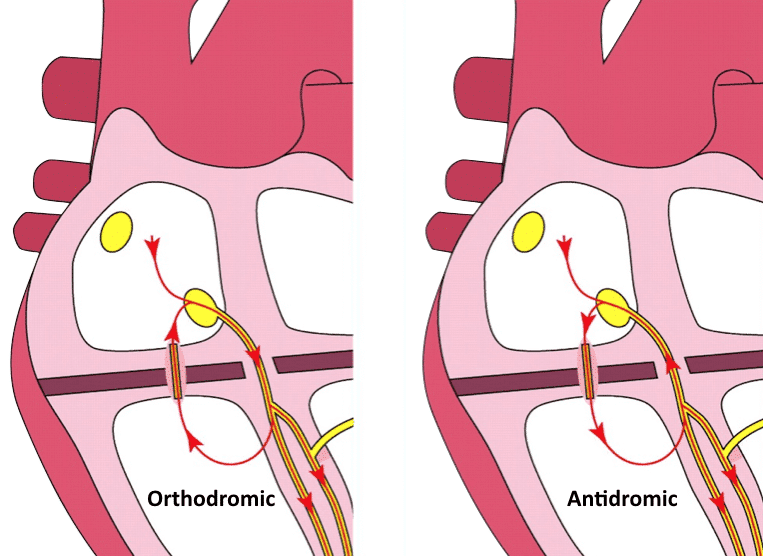

AVRT can be further divided into orthodromic (travelling in normal direction) or antidromic forms, based on the direction of re-entry conduction. Both have high rates, usually above 200 bpm.

Antidromic AVRT: Retrograde conduction through AV node

Orthodromic AVRT

In orthodromic AVRT, anterograde conduction occurs via the AV node, resulting in a normal direction of ventricular depolarisation. In the absence of pre-existing bundle branch block, this produces a narrow QRS complex.

This rhythm can appear very similar to AVNRT, but the RP interval can differentiate:

- In typical AVNRT, retrograde P waves occur early, so we either don’t see them (buried in QRS) or partially see them (pseudo R’ wave at terminal portion of QRS complex)

- In AVRT, retrograde P waves occur later, with a long RP interval > 70 msec

The anterograde portion of conduction is typically the “weak link” of the re-entry circuit – management options in the stable patient therefore target slowing conduction through the AV node. A stepwise approach similar to AVNRT can be employed, beginning with vagal manoeuvres followed by adenosine and/or verapamil.

Note that with administration of any AV nodal blocking drug, there is a very small but significant risk of inducing AF. If verapamil is used, patients should be observed for at least 4 hours to ensure AF does not develop as a consequence of AV nodal blockade.

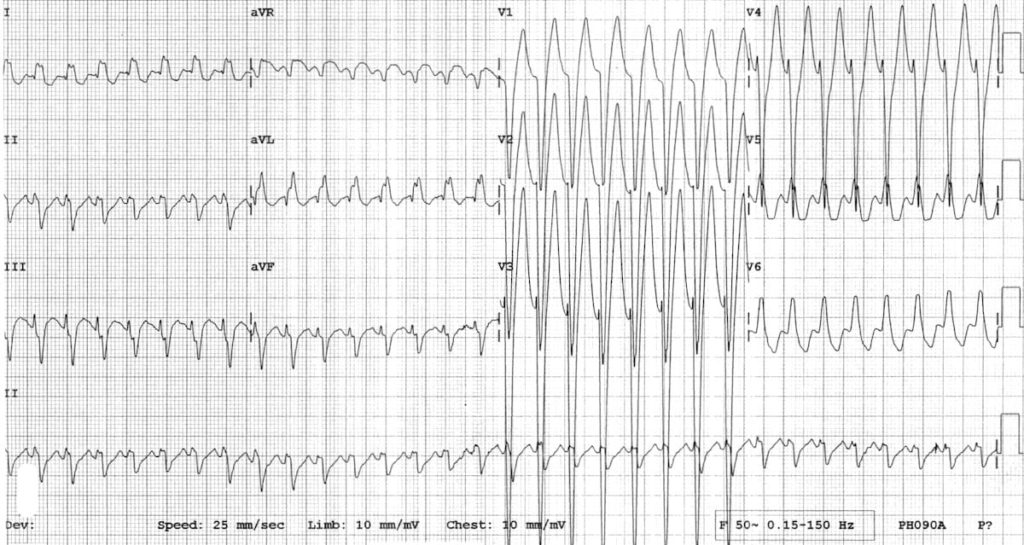

Antidromic AVRT

Antidromic AVRT is rare, and makes up only 5% of tachyarrhythmias in patients with WPW. As the name suggests, it involves anterograde conduction via the AP. Retrograde conduction is usually via the AV node, but can also be via another AP. The abnormal direction of ventricular depolarisation results in a broad complex tachycardia, which can be easily mistaken for VT.

Antidromic AVRT is often associated with a rapidly conducting anterograde AP. AV blockade through adenosine may interrupt this re-entry circuit, but as stated above there is a small risk of inducing AF. If this occurs it will likely precipitate cardiac arrest due to rapid conduction via the AP. As such, in a stable patient drug therapy should be targeted at the AP (procainamide would be our first line agent again).

If the patient is haemodynamically unstable, or there is any doubt as to the rhythm, we should presume a diagnosis of VT and treat accordingly.

- Tachyarrhythmias in patients with APs can be divided into two main categories – direct AV conduction (AF/flutter) and re-entry circuits (AVRT)

- In patients with AF, extremely rapid ventricular rates and beat-to-beat variation in QRS morphology suggest the presence of an AP

- In pre-excitation, AV nodal blocking drugs preference conduction via the AP, and should be avoided in patients with AF and antidromic AVRT. Procainamide is a suitable first-line agent in stable patients — it slows conduction through the AP, slowing ventricular rate and often causing reversion

- If in doubt, treat as VT!

Further reading

Related topics

Expert Review

- Smith SW. Wide Complex Tachycardia. Dr Smith’s ECG Blog. March 2013

References

- Brugada et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular tachycardia. European Society of Cardiology. Feb 2020

Further reading

- Wiesbauer F, Kühn P. ECG Mastery: Yellow Belt online course. Understand ECG basics. Medmastery

- Wiesbauer F, Kühn P. ECG Mastery: Blue Belt online course: Become an ECG expert. Medmastery

- Kühn P, Houghton A. ECG Mastery: Black Belt Workshop. Advanced ECG interpretation. Medmastery

- Rawshani A. Clinical ECG Interpretation ECG Waves

- Smith SW. Dr Smith’s ECG blog.

- Wiesbauer F. Little Black Book of ECG Secrets. Medmastery PDF

TOP 150 ECG Series

MBBS DDU (Emergency) CCPU. Adult/Paediatric Emergency Medicine Advanced Trainee in Melbourne, Australia. Special interests in diagnostic and procedural ultrasound, medical education, and ECG interpretation. Co-creator of the LITFL ECG Library. Twitter: @rob_buttner

Interventional cardiologist, ECG and hemodynamics fan. MD, Assoc. Prof. at Marmara University, Pendik T&R Hospital, Assoc. Editor at Archives of TSC, ESC National Prevention Coordinator

Help! I keep getting a normal axis with these two. To me, the QRS is upright in both leads I and aVF. Am I getting something wrong about the way I’m looking at it? I simply can’t get the RAD.

Yeah same, my answer is also normal axis for both the ecgs.

I think it’s tricky to see QRS in lead I because too many spikes, difficult to see which one is qrs, and which one is T wave. If you see other left leads like aVL, V5, V6, it’s clear that qrs is negative, it means that qrs in lead I is also negative

no right axis deviation in this ECG