Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM)

ECG features of HCM

- Left ventricular hypertrophy with increased precordial voltages and non-specific ST segment and T-wave abnormalities

- Deep, narrow (“dagger-like”) Q waves in lateral (I, aVL, V5-6) +/- inferior (II, III, aVF) leads

Other associated features may include:

- Left atrial enlargement (“P mitrale”) — left ventricular diastolic dysfunction may lead to compensatory left atrial hyertrophy

- Signs of WPW (short PR, delta wave) — ECG features of Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) were seen in 33% of patients with HCM in one study, and at least one genetic mutation has been identified that is associated with both conditions

- Dysrhythmias: atrial fibrillation and supraventricular tachycardias are common; PACs, PVCs, VT

- Giant precordial T-wave inversions in apical HCM

1) Voltage criteria for LVH in precordial and limb leads

2) Narrow, “dagger-like” Q waves in inferior and lateral leads

Q wave morphology

- Q waves seen in HCM can mimic prior myocardial infarction, although the Q-wave morphology is different:

- Infarction Q waves are typically > 40 ms duration

- Septal Q waves in HCM are < 40 ms

- Lateral Q waves are more common than inferior Q waves in HCM

Overview of HCM

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, previously termed hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM) or idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic stenosis (IHSS), is one of the most common inherited cardiac disorders:

- Prevalence ~1 in 500 people

- Annual mortality ~1-2%

- Number one cause of sudden cardiac death in young people

It is a heterogenous disorder produced by mutations in multiple genes coding for sarcomeric proteins (e.g. beta-myosin heavy chain, troponin T). Inheritance is primarily autosomal dominant, with variable penetrance. Over 150 mutations have been identified, explaining the variability in the clinical phenotype.

Structural changes

- The chief abnormality associated with HCM is left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), occurring in the absence of any inciting stimulus such as hypertension or aortic stenosis

- The degree and distribution of LVH is variable: mild hypertrophy (13-15 mm) or extreme myocardial thickening (30-60 mm) may be seen.

- The most commonly observed pattern is asymmetrical thickening of the anterior interventricular septum (= asymmetrical septal hypertrophy). This pattern has been classically associated with systolic anterior motion (SAM) of the mitral valve and dynamic left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction

- However, in the majority of cases (75%), HCM is not associated with LVOT obstruction, hence the name change from HOCM to HCM

- Other less common patterns of LVH include concentric hypertrophy (20% of cases) and apical hypertrophy (10%)

Pathophysiology of clinical manifestations

Processes responsible for clinical manifestations of HCM:

- Dynamic obstruction of the LVOT

- Left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, resulting from impaired relaxation and filling of the stiff and hypertrophied left ventricle (often associated with increased filling pressures)

- Abnormal intramural coronary arteries with thickened walls and narrowed lumens

- Chaotic, disorganised left ventricular architecture (“cellular disarray”) predisposing to abnormal transmission of electrical impulses, thus serving as a substrate for arrhythmogenesis

Clinical features

- Exertional syncope or pre-syncope — this is the most worrying symptom, suggesting dynamic LVOT obstruction ± ventricular dysrhythmia, with the potential for sudden cardiac death

- Symptoms of pulmonary congestion (e.g. exertional dyspnoea, fatigue, orthopnoea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea) due to left ventricular dysfunction

- Chest pain — may be typical anginal pain due to increased demand (thicker myocardial walls) and reduced supply (aberrant coronary arteries)

- Palpitations due to supraventricular or ventricular arrhythmias

Apical HCM

- This relatively uncommon form of HCM is seen most frequently in Japanese patients (13-25% of all HCM cases in Japan)

- There is localised hypertrophy of LV apex, causing a “spade-shaped” configuration of the LV cavity on ventriculography

- The classic ECG finding in apical HCM is giant T-wave inversion in the precordial leads

Useful Tip

- There is a small subset of patients with HCM who will have an abnormal ECG with no evidence of LVH on echo

- If there is clinical concern for HCM — i.e. syncope, chest pain and characteristic ECG changes — patients should be referred for a cardiac MRI if echo is unremarkable

ECG Examples

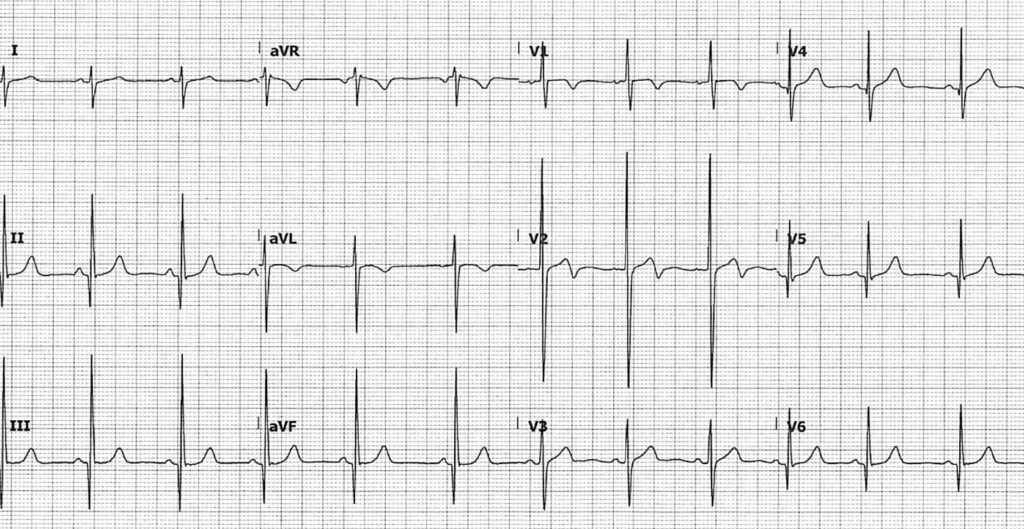

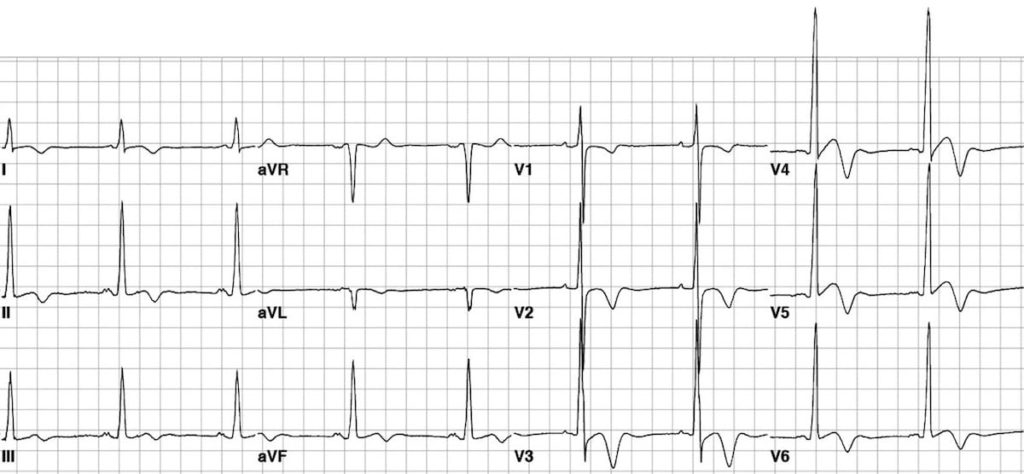

Example 1

Classic HCM pattern with asymmetrical septal hypertrophy:

- Voltage criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy.

- Deep narrow Q waves < 40 ms wide in the lateral leads I, aVL and V5-6.

This ECG was taken from a 30-year old man who presented with exertional lightheadedness and palpitations. The ECG was misread by the cardiology team as showing “left ventricular hypertrophy, lateral infarct age undetermined”.

The patient was discharged home and subsequently died of a VF arrest while running to catch a bus. Autopsy showed septal hypertrophy consistent with HCM.

Teaching Point: In a young patient presenting with exertional symptoms and an ECG that looks this this, think HCM — not “prior lateral infarction“!

This ECG and clinical vignette is reproduced from a fantastic review article by Kelly, Mattu and Brady (2007).

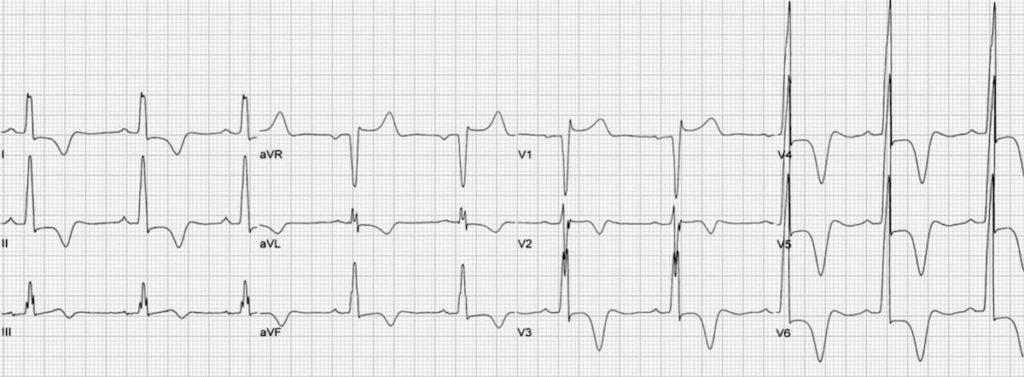

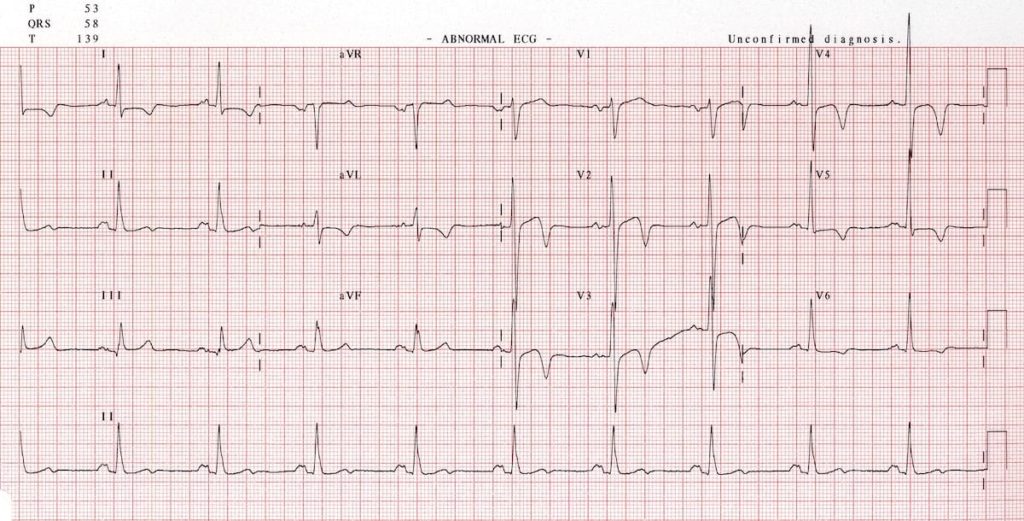

Example 2

HCM showing features of asymmetrical septal hypertrophy:

- Large precordial voltages.

- Deep, narrow, septal Q waves most prominent in leads I and aVL; also seen in V5-6.

This great ECG is reproduced from Kelly, Mattu and Brady (2007).

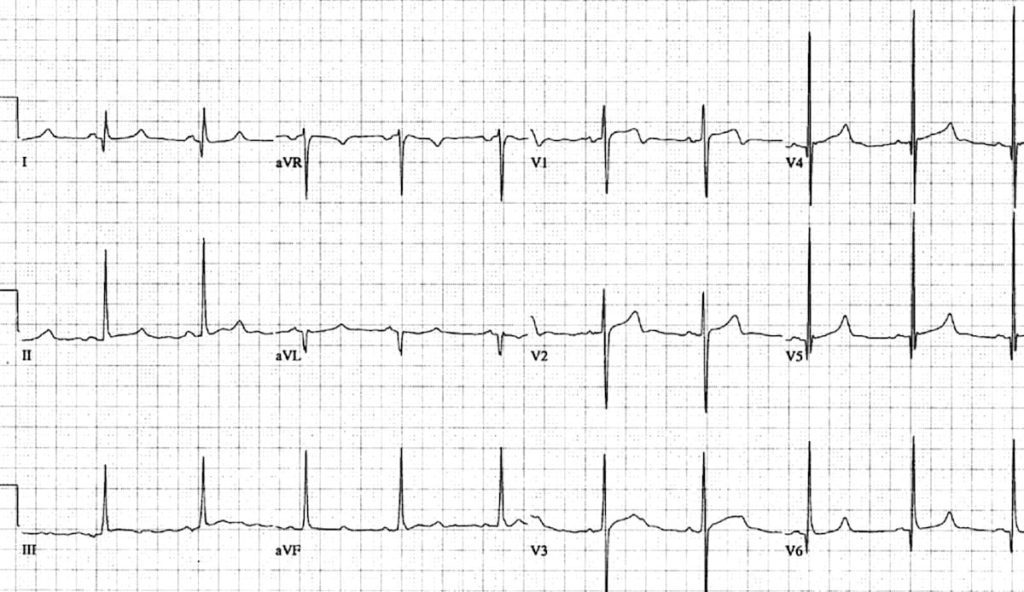

Example 3

This ECG shows the typical pattern of apical HCM:

- Large precordial voltages.

- Giant T wave inversions in the precordial leads

- Inverted T waves are also seen in the inferior and lateral leads.

This great ECG is reproduced from Hansen & Merchant (2007).

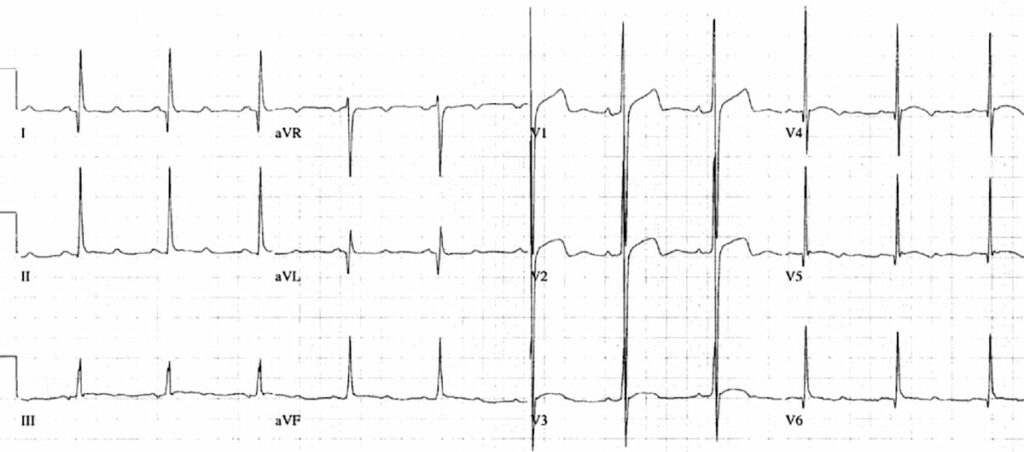

Example 4

Another example of apical HCM

- High precordial voltages.

- Deep T wave inversions in the precordial and high-lateral leads.

- There is also evidence of left atrial enlargement (“P mitrale”).

Videos

HCM video education

Related Topics

Advanced Reading

Online

- Wiesbauer F, Kühn P. ECG Mastery: Yellow Belt online course. Understand ECG basics. Medmastery

- Wiesbauer F, Kühn P. ECG Mastery: Blue Belt online course: Become an ECG expert. Medmastery

- Kühn P, Houghton A. ECG Mastery: Black Belt Workshop. Advanced ECG interpretation. Medmastery

- Rawshani A. Clinical ECG Interpretation ECG Waves

- Smith SW. Dr Smith’s ECG blog.

- Wiesbauer F. Little Black Book of ECG Secrets. Medmastery PDF

Textbooks

- Zimmerman FH. ECG Core Curriculum. 2023

- Mattu A, Berberian J, Brady WJ. Emergency ECGs: Case-Based Review and Interpretations, 2022

- Straus DG, Schocken DD. Marriott’s Practical Electrocardiography 13e, 2021

- Brady WJ, Lipinski MJ et al. Electrocardiogram in Clinical Medicine. 1e, 2020

- Mattu A, Tabas JA, Brady WJ. Electrocardiography in Emergency, Acute, and Critical Care. 2e, 2019

- Hampton J, Adlam D. The ECG Made Practical 7e, 2019

- Kühn P, Lang C, Wiesbauer F. ECG Mastery: The Simplest Way to Learn the ECG. 2015

- Grauer K. ECG Pocket Brain (Expanded) 6e, 2014

- Surawicz B, Knilans T. Chou’s Electrocardiography in Clinical Practice: Adult and Pediatric 6e, 2008

- Chan TC. ECG in Emergency Medicine and Acute Care 1e, 2004

LITFL Further Reading

- ECG Library Basics – Waves, Intervals, Segments and Clinical Interpretation

- ECG A to Z by diagnosis – ECG interpretation in clinical context

- ECG Exigency and Cardiovascular Curveball – ECG Clinical Cases

- 100 ECG Quiz – Self-assessment tool for examination practice

- ECG Reference SITES and BOOKS – the best of the rest

ECG LIBRARY

Emergency Physician in Prehospital and Retrieval Medicine in Sydney, Australia. He has a passion for ECG interpretation and medical education | ECG Library |

MBBS DDU (Emergency) CCPU. Adult/Paediatric Emergency Medicine Advanced Trainee in Melbourne, Australia. Special interests in diagnostic and procedural ultrasound, medical education, and ECG interpretation. Co-creator of the LITFL ECG Library. Twitter: @rob_buttner