Common paediatric arrhythmias

- Normal paediatric ECG

- Paediatric ECG lead placement

- Stepwise assessment of the paediatric ECG

- Common paediatric arrhythmias

Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT)

SVT is common in adult and paediatric populations. A more in-depth overview of SVT, including in the adult patient, can be found here.

SVT is the most common dysrhythmia seen in the paediatric population, and comprises over 90% of paediatric dysrhythmias. Of children presenting with SVT:

- Half will have no underlying heart disease

- 1⁄4 will have WPW

- Almost 1⁄4 will have congenital heart disease

Characteristics in the paediatric population

- Rapid, regular usually narrow (< 80 ms) complex tachycardia:

- 220 – 320 bpm in infants

- 150 – 250 bpm in older children

- P wave is usually invisible, or if visible is abnormal in axis and may precede or follow the QRS complex (retrograde P waves)

- 90% are of the re-entrant type

Clinical significance

- SVT may be well tolerated in infants for 12-24 hours. Congestive heart failure later manifests with irritability, poor perfusion, pallor, poor feeding, and then rapid deterioration

- Note that > 95% of wide complex tachycardias in paediatrics are not VT, but SVT with aberrancy:

- SVT with BBB (in pre-existing congenital heart disease)

- Accessory pathway re-entrant SVT

The presence of AV block will interrupt any re-entrant tachycardia that involves the AV node; therefore adenosine (transiently blocks AV conduction) works well for these rhythms. Several atrial rhythms; atrial flutter, atrial fibrillation and sinoatrial node re-entry tachycardia are also considered subgroups of re-entrant SVT. These do not respond to adenosine but the transient slowing of the ventricular rate may unmask the atrial activity and therefore underlying cause of the SVT. A running rhythm strip is therefore imperative.

Management

A 12-lead ECG in SVT and post-conversion is essential. Monitor with a rhythm strip during manoeuvres – this allows later assessment of underlying rhythm in unclear cases.

1. Acute treatment: Aim to induce AV nodal slowing

Vagal manoeuvres

- Infants: ice plus water in bag placed on face for up to 10 seconds – often effective

- Older children: carotid sinus massage, valsalva manoeuvre (30 – 60 seconds), deep inspiration/cough/gag reflex, headstand

- Causes transient AV nodal blockade, interrupting re-entry pathway through AV node

- Half life < 10seconds

- Side effects of flushing and bronchospasm are short-lived

- Give 100mcg/kg rapidly into a large vein. Repeat after 2 minutes with 250mcg/kg

- Maximum total dose 12mg

Cardioversion

- Be very wary of cardioverting an “unstable” child in SVT in ED who remains conscious to the point of requiring sedation or anaesthesia

- Rapid deterioration of the “SVT-stressed” myocardium may occur with anaesthesia

- If shock is present, synchronous DCCV is indicated at 0.5-2 J/kg (monophasic)

2. Chronic treatment

Conducted as an inpatient; either medical or surgical/catheter pathway ablation.

ECG Examples

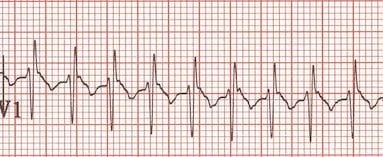

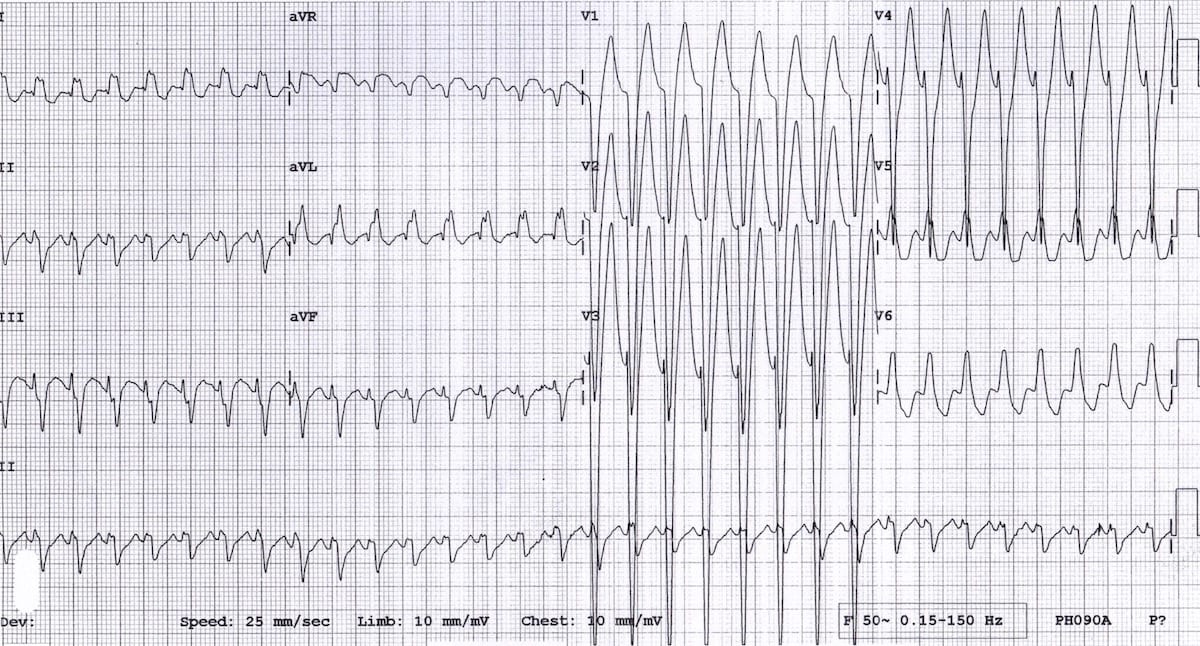

Example 1(a) – Narrow-complex tachycardia in a 12-day old boy

- Rapid narrow complex regular tachycardia at around 300 bpm

Example 1(b) – Narrow-complex tachycardia in a 12-day old boy — paper speed at 50mm/sec

- The same patient with the paper at double speed (50 mm/s)

- There are no visible P waves — this is an AV nodal re-entry tachycardia

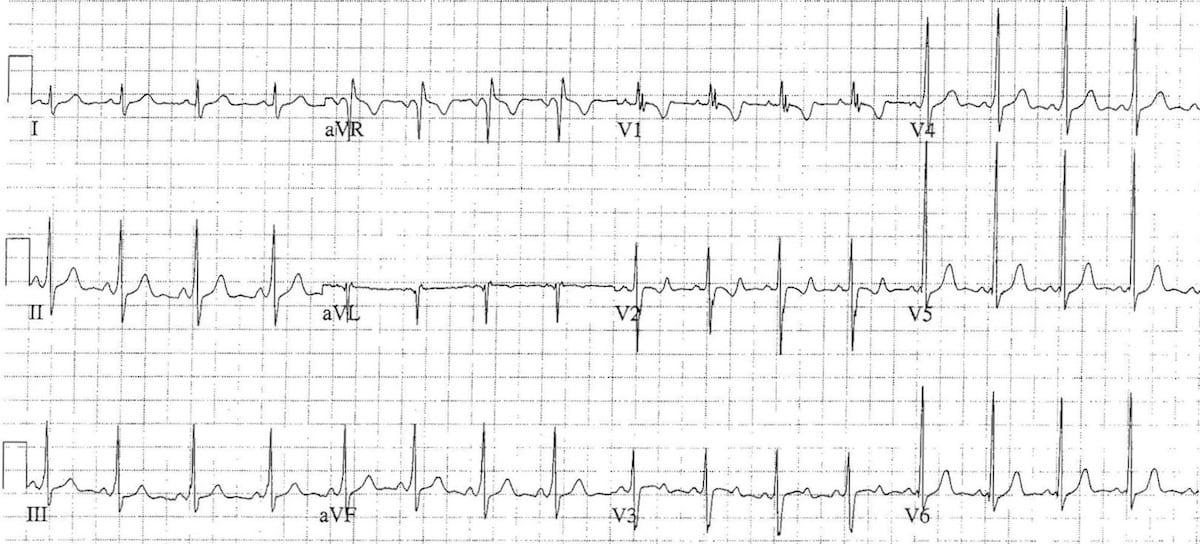

Example 1(c) – normal sinus rhythm in a 12-day old boy

- This is the same patient after reversion to sinus rhythm

- Slightly peaked P waves, right axis and tall R waves in V1 are all within normal limits for the patients age

Automatic SVT

SVT due to abnormal or accelerated normal automaticity (e.g sympathomimetics). Usually accelerate (‘warm up’) and decelerate (‘cool down’) gradually.

- Sinus tachycardia: enhanced automatic rhythm. Rate varies with physiological state.

- Atrial tachycardia: non-reciprocating or ectopic atrial tachycardia – rapid firing of a single focus in the atria. Slower heart rate (130-160). Rare. Usually constant rather than paroxysmal.

- Junctional ectopic tachycardia: difficult to treat, usually occurs in setting of post extensive atrial surgery. Rapid firing of a single focus in the AV node. Slower rhythm – 120-200bpm.

Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome

WPW syndrome is characterised by the occurrence of SVT plus specific ECG findings in sinus rhythm. The characteristic pre-excitation is evidenced by a short PR interval and widened QRS with a slurred upstroke or delta wave.

It is caused by ventricular excitation occurring earlier via the accessory pathway than it would have occurred via the normal AV node alone. With the onset of SVT, conduction reverses (becomes V to A) in the accessory pathway as part of the circular rhythm.

In a small number of patients with WPW, accessory pathway conduction is A to V in SVT (and reversed to become V to A in the AV node). This results in an anomalous ventricular activation sequence and a wide complex QRS (> 120 msec) followed by retrograde P waves which may be difficult to differentiate from VT.

ECG Examples

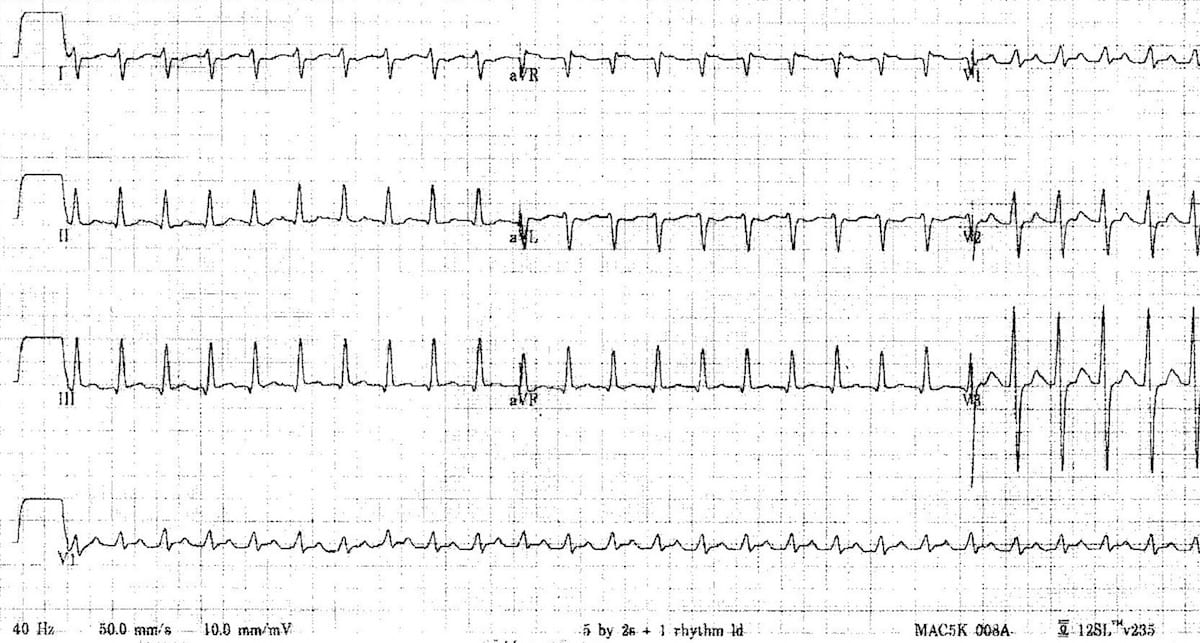

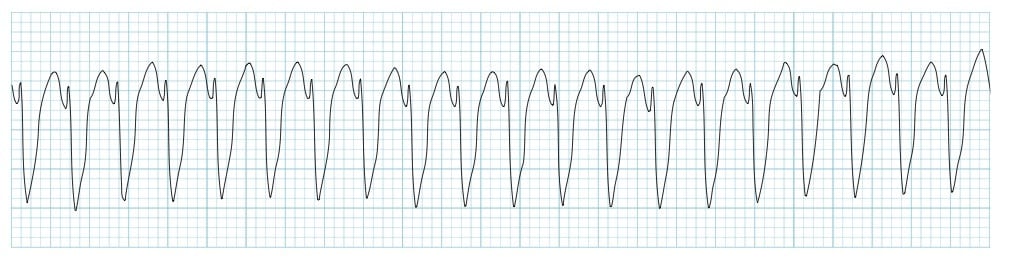

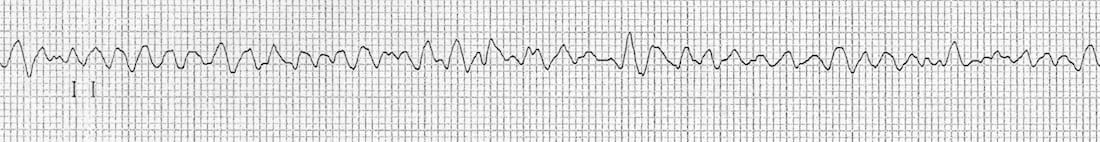

Example 2(a)

Antidromic AVRT due to WPW in a 5-year old boy.

- Broad complex tachycardia at ~280 bpm

- This could easily be mistaken for VT; however, remember that >95% of broad complex tachycardias in paediatrics are actually SVT with aberrancy (usually a re-entrant tachycardia)

- This is an antidromic atrioventricular re-entry tachycardia due to WPW

Example 2(b) – WPW in a 5-year-old boy

This is the resting ECG of the same 5-year boy, shortly after reversion to sinus rhythm. Note:

- Very short PR interval (< 100 ms)

- Slurred upstroke to the QRS complexes = the delta wave

- In contrast to WPW in adults, the QRS complex is not particularly wide (80-100 ms)

- There is a “pseudoinfarction” Q wave in aVL (simply an inverted delta wave)

- Rightward axis (+90 degrees), RSR’ pattern in V1 and T-wave inversion in V1-2 is normal for age.

See how subtle these changes are compared to WPW in adults.

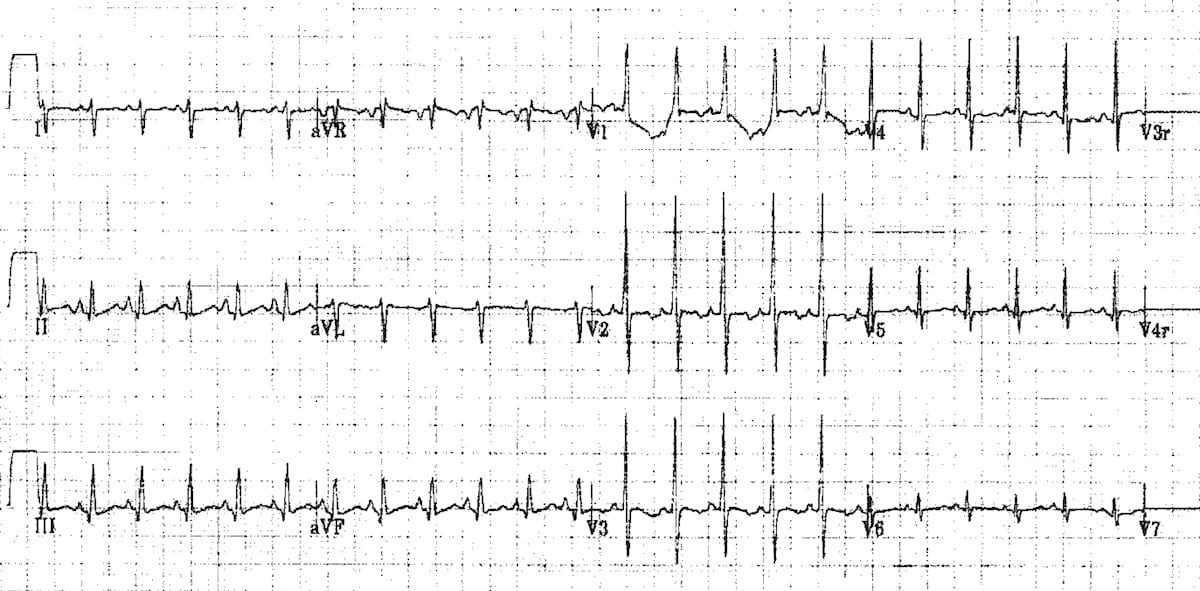

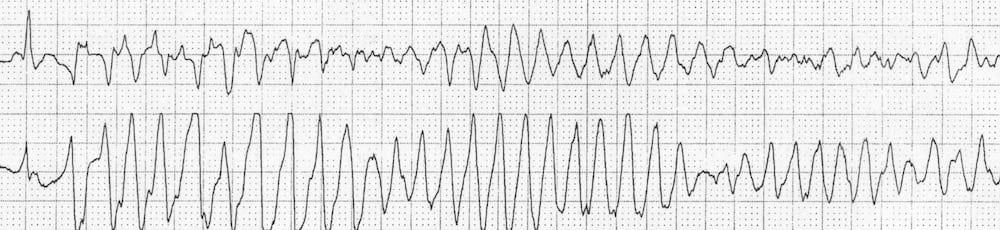

Example 3

Antidromic AVRT due to Wolf-Parkinson-White in a 15-year old boy. This case is discussed further in ECG Exigency 004.

Example 4

Another example of Wolf-Parkinson-White, this time in a 7-year old child, demonstrating:

- Short PR interval

- Delta waves

- Mild QRS prolongation

- Rightward axis (+90 degrees), dominant R wave in V1 and inverted/biphasic T waves in V1-2 are normal for the patients age

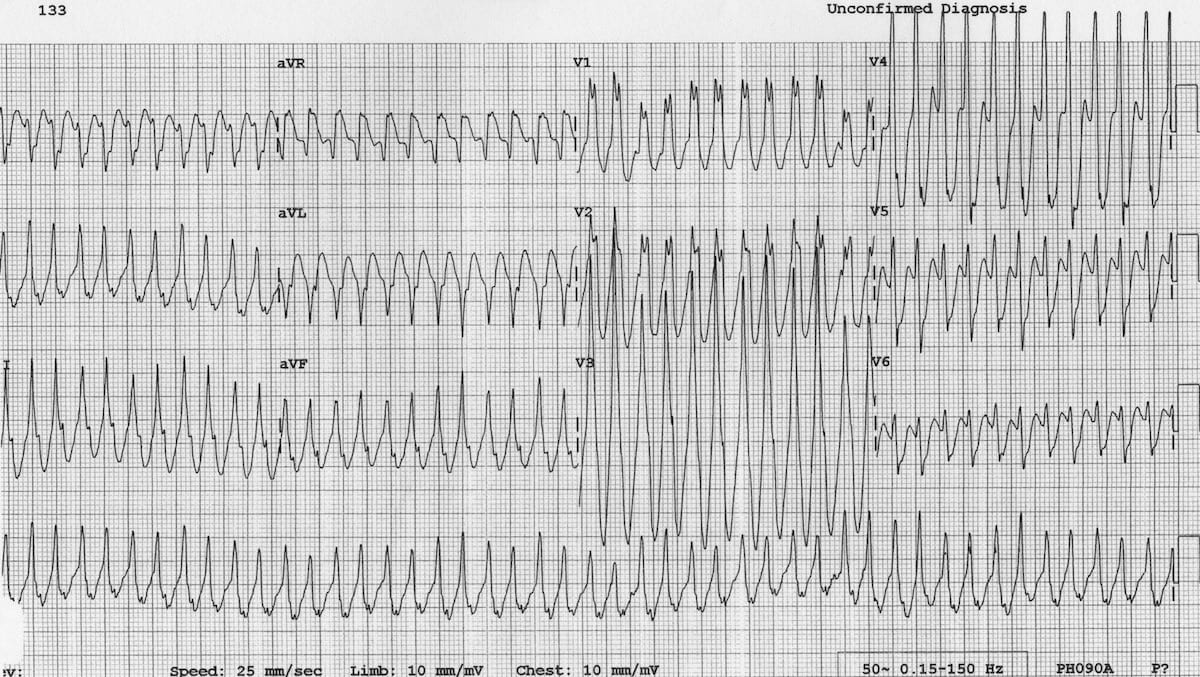

Broad Complex Tachydysrhythmias

VT is extremely rare in children. There is usually a history of structural (congenital) cardiac abnormality.

Polymorphic VT / Torsades de Pointes

Occurs in long QT syndrome and with some drugs. Causes syncope if self-terminating or cardiac arrest if prolonged (i.e. degenerates to VF).

Also extremely rare in children and associated with congenital cardiac abnormalities. Treatment is DC shock at 4 joules / kg.

Related Topics

- Paediatric ECG Basics

- Normal paediatric ECG

- Paediatric lead placement

- Stepwise assessment of the paediatric ECG

- ECG approach in syncope

References

- Paediatric Electrocardiography by Steve Goodacre and Karen McLeod, from the BMJ’s “ABC of Clinical Electrocardiography” series (2002)

- O’Connor M, McDaniel N, Brady WJ. The pediatric electrocardiogram. Part I: Age-related interpretation. Am J Emerg Med. 2008 Feb;26(2):221-8

- Evans WN1, Acherman RJ, Mayman GA, Rollins RC, Kip KT. Simplified pediatric electrocardiogram interpretation. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2010 Apr;49(4):363-72.

Advanced Reading

Online

- Wiesbauer F, Kühn P. ECG Mastery: Yellow Belt online course. Understand ECG basics. Medmastery

- Wiesbauer F, Kühn P. ECG Mastery: Blue Belt online course: Become an ECG expert. Medmastery

- Kühn P, Houghton A. ECG Mastery: Black Belt Workshop. Advanced ECG interpretation. Medmastery

- Rawshani A. Clinical ECG Interpretation ECG Waves

- Smith SW. Dr Smith’s ECG blog.

- Wiesbauer F. Little Black Book of ECG Secrets. Medmastery PDF

Textbooks

- Zimmerman FH. ECG Core Curriculum. 2023

- Mattu A, Berberian J, Brady WJ. Emergency ECGs: Case-Based Review and Interpretations, 2022

- Straus DG, Schocken DD. Marriott’s Practical Electrocardiography 13e, 2021

- Brady WJ, Lipinski MJ et al. Electrocardiogram in Clinical Medicine. 1e, 2020

- Mattu A, Tabas JA, Brady WJ. Electrocardiography in Emergency, Acute, and Critical Care. 2e, 2019

- Hampton J, Adlam D. The ECG Made Practical 7e, 2019

- Kühn P, Lang C, Wiesbauer F. ECG Mastery: The Simplest Way to Learn the ECG. 2015

- Grauer K. ECG Pocket Brain (Expanded) 6e, 2014

- Surawicz B, Knilans T. Chou’s Electrocardiography in Clinical Practice: Adult and Pediatric 6e, 2008

- Chan TC. ECG in Emergency Medicine and Acute Care 1e, 2004

LITFL Further Reading

- ECG Library Basics – Waves, Intervals, Segments and Clinical Interpretation

- ECG A to Z by diagnosis – ECG interpretation in clinical context

- ECG Exigency and Cardiovascular Curveball – ECG Clinical Cases

- 100 ECG Quiz – Self-assessment tool for examination practice

- ECG Reference SITES and BOOKS – the best of the rest

ECG LIBRARY

Emergency Physician in Prehospital and Retrieval Medicine in Sydney, Australia. He has a passion for ECG interpretation and medical education | ECG Library |

MBBS DDU (Emergency) CCPU. Adult/Paediatric Emergency Medicine Advanced Trainee in Melbourne, Australia. Special interests in diagnostic and procedural ultrasound, medical education, and ECG interpretation. Co-creator of the LITFL ECG Library. Twitter: @rob_buttner