Laryngospasm

OVERVIEW

- Laryngospasm is potentially life-threatening closure of the true vocal chords resulting in partial or complete airway obstruction unresponsive to airway positioning maneuvers.

- can occur spontaneously, most commonly associated with extubation or ENT procedures

CAUSES

Local

- extubation — especially children with URTI symptoms

- intubation and airway manipulation (especially if insufficiently sedated)

- ENT procedures

- fluids (e.g. blood, secretions, vomitus)

- foreign body

- aspiration

- reflux

- near drowning

Systemic

- drugs e.g. acute dystonic reactions; rarely associated with ketamine procedural sedation

- tetanus

- hypocalcemia

- strynchnine poisoning

- vocal cord dysfunction

- epilepsy (rare)

- sleep-related laryngospasm

- psychogenic pseudo-laryngospasm

CLINICAL FEATURES

Laryngospasm:

- Laryngospasm may be preceded by a high-pitched inspiratory stridor — some describe a characteristic ‘crowing‘ noise — followed by complete airway obstruction.

- It can occur without any warning signs.

- It should be suspected whenever airway obstruction occurs, particularly in the absence of an obvious supraglottic cause.

- Laryngospasm may not be obvious — it may present as increased work of breathing (e.g. tracheal tug, indrawing), vomiting or desaturation.

Complete airway obstruction is characterized by:

- No chest wall movement with no breath sounds on auscultation

- No stridor or airway sounds

- Sudden loss of carbon dioxide waveform

- Inability to manually ventilate with bag-mask ventilation

Complications:

- hypoxia and bradycardia

- negative pressure pulmonary edema

- ischemic end organ injury (e.g. stroke, hypoxic encephalopathy)

- death

MANAGEMENT

- Tell the proceduralist to stop the procedure.

- Call for expert help. Ensure equipment for difficult intubation is at hand.

- Administer 100% oxygen through a mask with a tight seal and a closed expiratory valve to try to force the vocal cords open with positive pressure. Hypoxia can occur rapidly in children when ventilation is inadequate.

- Use suction to clear the airway of blood and secretions – but only if the child is adequately oxygenated.

- Attempt manual ventilation while continuing to apply continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP).

- Attempt to break the laryngospasm by applying painful inward and anterior pressure at ‘Larson’s point‘ bilaterally while performing a jaw thrust. Larson’s point is also called the ‘laryngospasm notch‘.

- Consider deepening sedation/ anesthesia (e.g. low dose propofol) to reduce laryngospasm.

- If hypoxia supervenes consider administering suxamethonium. A dose of only 0.1-0.5 mg/kg may be sufficient, but in severe laryngospasm administer a full dose (1-2 mg/kg IV) and perform intubation. If there is no IV access administer the suxamethonium IM (3-4 mg/kg). Many experts advocate IM injection into the tongue.

- Be prepared for bradycardia and cardiac arrest as a result of airway manipulation and/or suxamethonium administration in the hypoxic child. Correct hypoxia urgently and administer atropine (0.02mg/kg) for bradycardia.

- Laryngospasm is usually brief and may be followed by a gasp – you may need to wait for this moment when attempting to pass a tracheal tube. A chest thrust maneuver immediately preceding intubation may temporarily open the vocal cords and allow passage of the tube.

- Laryngospasm may recur as neuromuscular blockade wears off.

- Keep the airway clear and monitor for negative pressure pulomnary oedema.

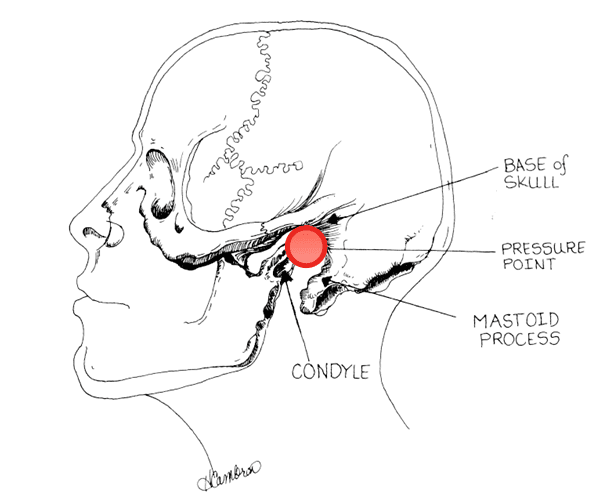

LARYNGOSPASM NOTCH

aka Larson’s point

Where is the ‘laryngospasm notch‘? According to Phil Larson:

“This notch is behind the lobule of the pinna of each ear. It is bounded anteriorly by the ascending ramus of the mandible adjacent to the condyle, posteriorly by the mastoid process of the temporal bone, and cephalad by the base of the skull.”

References and Links

CCC Airway Series

Emergencies: Can’t Intubate, Can’t Intubate, Can’t Oxygenate (CICO), Laryngospasm, Surgical Cricothyroidotomy

Conditions: Airway Obstruction, Airway in C-Spine Injury, Airway mgmt in major trauma, Airway in Maxillofacial Trauma, Airway in Neck Trauma, Angioedema, Coroner’s Clot, Intubation of the GI Bleeder, Intubation in GIH, Intubation, hypotension and shock, Peri-intubation life threats, Stridor, Post-Extubation Stridor, Tracheo-esophageal fistula, Trismus and Restricted Mouth Opening

Pre-Intubation: Airway Assessment, Apnoeic Oxygenation, Pre-oxygenation

Paediatric: Paediatric Airway, Paeds Anaesthetic Equipment, Upper airway obstruction in a child

Airway adjuncts: Intubating LMA, Laryngeal Mask Airway (LMA)

Intubation Aids: Bougie, Stylet, Airway Exchange Catheter

Intubation Pharmacology: Paralytics for intubation of the critically ill, Pre-treatment for RSI

Laryngoscopy: Bimanual laryngoscopy, Direct Laryngoscopy, Suction Assisted Laryngoscopy Airway Decontamination (SALAD), Three Axis Alignment vs Two Curve Theory, Video Laryngoscopy, Video Laryngoscopy vs. Direct

Intubation: Adverse effects of endotracheal intubation, Awake Intubation, Blind Digital Intubation, Cricoid Pressure, Delayed sequence intubation (DSI), Nasal intubation, Pre-hospital RSI, Rapid Sequence Intubation (RSI), RSI and PALM

Post-intubation: ETT Cuff Leak, Hypoxia, Post-intubation Care, Unplanned Extubation

Tracheostomy: Anatomy, Assessment of swallow, Bleeding trache, Complications, Insertion, Insertion timing, Literature summary, Perc. Trache, Perc. vs surgical trache, Respiratory distress in a trache patient, Trache Adv. and Disadv., Trache summary

Misc: Airway literature summaries, Bronchoscopic Anatomy, Cuff Leak Test, Difficult airway algorithms, Phases of Swallowing

Social media and web resources

- Anaesthetic Addler 001 — Nasal foreign body, ketamine and laryngospasm

- Resus.ME — Laryngospasm after Ketamine

Journal articles and textbooks

- Hobaika AB, Lorentz MN. [Laryngospasm]. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2009 Jul-Aug;59(4):487-95. Review. Portuguese. PubMed PMID: 19669024. [Free fulltext]

- Larson CP Jr. Laryngospasm–the best treatment. Anesthesiology. 1998 Nov;89(5):1293-4. PubMed PMID: 9822036. [Free fulltext]

- Orliaguet GA, Gall O, Savoldelli GL, Couloigner V. Case scenario: perianesthetic management of laryngospasm in children. Anesthesiology. 2012 Feb;116(2):458-71. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318242aae9. Review. PubMed PMID: 22222477. [Free fulltext]

- Salem MR, Crystal GJ, Nimmagadda U. Understanding the mechanics of laryngospasm is crucial for proper treatment. Anesthesiology. 2012 Aug;117(2):441-2. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31825f02b4. PubMed PMID: 22828433. [Free fulltext]

Critical Care

Compendium

Chris is an Intensivist and ECMO specialist at The Alfred ICU, where he is Deputy Director (Education). He is a Clinical Adjunct Associate Professor at Monash University, the Lead for the Clinician Educator Incubator programme, and a CICM First Part Examiner.

He is an internationally recognised Clinician Educator with a passion for helping clinicians learn and for improving the clinical performance of individuals and collectives. He was one of the founders of the FOAM movement (Free Open-Access Medical education) has been recognised for his contributions to education with awards from ANZICS, ANZAHPE, and ACEM.

His one great achievement is being the father of three amazing children.

On Bluesky, he is @precordialthump.bsky.social and on the site that Elon has screwed up, he is @precordialthump.

| INTENSIVE | RAGE | Resuscitology | SMACC