Name that murmur

Eponymythology: The myths behind the history

An alphabetic review of eponymythology associated with named cardiac murmurs. We review related eponyms, the person behind their origin, their relevance today, and modern terminology.

Austin Flint murmur

Mid-diastolic, low-pitched rumbling murmur, heard best at the apex with the patient leaning forward and breathing out.

Occurs in aortic regurgitation as a result of the vibration of the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve due to the regurgitant jets from the left atrium and aorta. The striking of these regurgitant jets often cause the premature closure of the mitral leaflets, commonly mistaken for mitral stenosis

The murmur is oftener rough than soft. The roughness is often peculiar. It is a blubbering sound, resembling that produced by throwing the lips or the tongue into vibration with the breath of respiration

Flint A. 1862: 50

In some cases in which free aortic regurgitation exists, the left ventricle becoming filled before the auricles contract, the mitral curtains are floated out and the valve closed when the mitral current takes place, and, under the circumstance, the murmur may be produced by the current just named, although no mitral lesion exists.

Flint A. 1862: 53

- Austin Flint (1812-1886) was an American Physician.

- Flint A. On Cardiac Murmurs. American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 1862; 44: 29-54.

Bruit de Roger (Roger’s murmur)

Loud holosystolic murmur of a ventricular septal defect (VSD). Best heard at the left upper sternal border, accompanied by a harsh thrill most often compared to the sound of a ‘rushing waterfall’. The smaller the defect, the greater the turbulence of flow and therefore the louder the murmur.

In 1879 Roger provided the first clinicopathological overview, through the correlation of his autopsy findings of interventricular defects with the murmurs previously documented in patients’ records.

…a murmur loud and long; it is single, begins at systole and is prolonged so as to hide the natural tic-tac; it has its maximum… in the upper third of the precardial region; it is median, like the septum itself

Roger 1879

- Henri-Louis Roger (1809 – 1891) was a French paediatrician.

- Roger H. Recherches cliniques sur la communication congenitale des deux coeurs, par inocclusion du septum interventriculaire. Bulletin de l’Academie de Médecine, 1879. 2me serie, VIII, 1074-94, 1189-1191.

Cabot-Locke murmur

Early diastolic murmur, no associated ‘decrescendo’ phase. Observed in patients with severe anaemia. The murmur resolves with treatment of the anaemia. There is no functional valvular abnormality present

In cases of intense anaemia, when the red cells are reduced to or below 1,000,000 per cu. mm, one occasionally hears diastolic murmurs not to be explained by permanent dilatation of the aortic ring nor as “cardio-respiratory murmurs”, and not due to a diastolic accentuation of a venous hum. The cause of these murmurs is obscure

Cabot R, Locke E. 1903: 120

- Richard Clarke Cabot (1868-1939) was an American physician.

- Edwin Allen Locke (1874-1971) was an American Physician

- Cabot RC, Locke EA. On the occurrence of diastolic murmurs without lesions of the aortic or pulmonary valves. Johns Hopkins Hospital Bulletin. 1903; 14: 115-20

Carey Coombs murmur

Short mid-diastolic murmur caused by active rheumatic carditis with mitral-valve inflammation

Similar to the mid-diastolic rumble of mitral stenosis but distinguished by the absence of an opening snap; presystolic accentuation; or a loud first sound.

Next the apical second sound becomes doubled and then, but often not till some time after, a murmur is added to the second half of this second sound. This, hard to distinguish at first, lengthens and strengthens till at last it runs into the beginning of the next cycle, becoming, in fact, a pre-systolic murmur. This is not as rough and loud as that of mitral obstruction and it is not due to valvular disease.

Coombs CF. Bristol Med Chir J (1907)

Carey Coombs murmur which is now largely obsolete with the global reduction in cases of rheumatic heart disease..

- Carey Franklin Coombs (1879-1932) was a British cardiologist.

- Coombs CF. Rheumatic Carditis in Childhood. Bristol Medico-Chirurgical Journal. 1907; 25(97): 193–200.

Cole-Cecil murmur

Early diastolic murmur of aortic insufficiency with radiation to the axilla.

Cole and Cecil examined 17 patients with provisional diagnosis of aortic insufficiency and mapped the site of maximal intensity and axillary radiation of the early diastolic murmur.

Having our attention drawn to the localization of an aortic diastolic murmur in the axilla we began to pay special attention to the occurrence of this murmur, and decided to make an accurate study of the distribution of the diastolic murmur in a number of cases of aortic insufficiency.

We foresee that the chief objection that will be raised to our description of the axillary aortic diastolic murmur will be that we have been listening to the diastolic mitral murmur (either a true stenotic murmur or a Flint murmur) which is transmitted into the axilla. We feel convinced, however, that such objections are not valid. The fact that the murmur described has been of exactly the same kind and quality as that heard at the base makes it seem almost certain that both have an identical origin.

Cole and Cecil 1908

- Rufus Ivory Cole (1872 – 1966) was an American physician

- Arthur Bond Cecil (1885 – 1967) was an American surgeon and urologist.

- Cole R, Cecil AB. The Axillary Diastolic Murmur in Aortic Insufficiency. Johns Hopkins Hospital Bulletin. 1908; 19: 353-361

Dock’s murmur

Early diastolic murmur similar to that of aortic regurgitation and is heard at the left second or third intercostal space. Similar to that of aortic regurgitation with an additional presystolic accentuation.

Associated with severe stenosis of the left anterior descending coronary artery. The murmur produced is diastolic since the coronary arteries fill in diastole. It is described as early diastolic and decrescendo sounding similar to the murmur of aortic regurgitation.

…when he [the patient] is erect, one can record a continuous, high-pitched diastolic murmur, with striking early and late (presystolic) accentuation…a decrescendo early diastolic murmur and diamond-shaped high pitched presystolic murmur.

In this area (left of midline, third interspace), but only when he is erect, one can record a continuous, high-pitched diastolic murmur, with striking early and late (presystolic) accentuation. It seems likely this is due to a coronary A-V (atrioventricular) fistula, or a coronary anomaly with one vessel entering the pulmonary artery and retrograde flow from collaterals connecting with the normal artery.

Dock W, Zoneraich S. 1967

- William Dock (1898-1990) was an American cardiologist.

- Dock W. Atherosclerosis: the facts and the mysteries. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1967 Sep;43(9):792-7

Gibson murmur

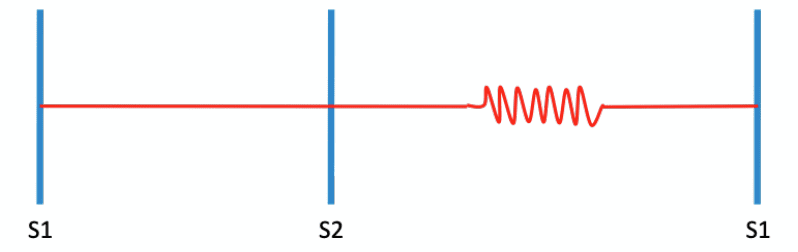

Long rumbling continuous (machinery) murmur occupying most of systole and diastole, most commonly localized in the second left interspace near the sternum.

Usually indicative of patent ductus arteriosus. The murmur results from continuous flow from aorta to pulmonary artery since aortic pressure is higher than pulmonary pressure throughout cardiac cycle.

It persists throughout the second sound, and dies away gradually during the long pause. The murmur is distinctly rough and thrilling in its character. It begins, however, somewhat softly, and increases in intensity so as to reach its acme just about, or immediately after, the incidence of the second sound, and from that point gradually wanes till its termination.

Gibson GA, 1906

- George Alexander Gibson (1854-1913) was a Scottish physician.

- Gibson GA. A clinical lecture on persistent ductus arteriosus. Med Press Circular 1906; 132: 572-574.

Graham Steell murmur

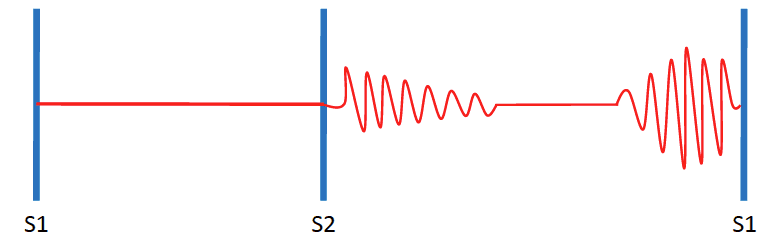

Soft, blowing, decrescendo early diastolic murmur. Best heard at the left sternal edge, second intercostal space in full inspiration. Associated with pulmonary incompetence caused by pulmonary hypertension.

In cases of mitral obstruction there is occasionally heard over the pulmonary area (the sternal extremity of the third left costal cartilage), and below this region, for the distance of an inch or two along the left border of the sternum, and rarely over the lowest part of the bone itself, a soft blowing diastolic murmur immediately following, or, more exactly, running off from the accentuated second sound, while the usual indications of aortic regurgitation afforded by the pulse, etc., are absent.

The maximum intensity of the murmur may be regarded as situated at the sternal end of the third and fourth intercostal spaces. When the second sound is reduplicated, the murmur proceeds from its latter part. That such a murmur as I have described does exist, there can, I think, be no doubt.

Steel G. 1888

- Graham Steell (1851-1942) was a Scottish physician and cardiologist.

- Steell G. Murmur of high-pressure in pulmonary artery. The Medical Chronicle (Manchester). 1888; 9: 182-186

Key-Hodgkin Murmur

A diastolic murmur of aortic regurgitation with a raspy quality likened to the sound of ‘a saw cutting through wood‘ (bruit de scie). Hodgkin correlated the murmur with retroversion of the aortic valve leaflets seen post mortem.

Key is credited with first drawing Hodgkin’s attention to the problem of aortic incompetence. Hodgkin addressed this association in his open letters to Key which he read in February 1827 before the Hunterian Society

My Dear friend. Thou will probably recollect having pointed out to me, a few months ago, a particular state of the valves of the aorta, which, by admitting of their falling back towards the ventricle, unfits them for the performance of their function

The impulse of the heart was not particularly feeble, but was considerably diffused; the sound very general over the whole left side, and nearly the whole of the right side of the chest, with the exception of the superior part of the chest. Each contraction appeared lengthened, accompanied with a purring, thrilling or sawing kind of noise

Hodgkin. On retroversion of the valves of the aorta. Read before the Hunterian Society Feb 21, 1827

- Charles Aston Key (1793-1849) was an English surgeon.

- Thomas Hodgkin (1798-1866) was an English physician and pathologist

- Hodgkin T. On retroversion of the valves of the aorta. Lond Med Gaz 1829; 3: 433-443.

Rivero-Carvallo sign

Accentuation of the murmur of tricuspid regurgitation and tricuspid stenosis with inspiration. Auscultation is performed during post-inspiratory apnoea and the loudness of the systolic murmur is compared to its loudness during post-expiratory apnoea.

The murmur of tricuspid insufficiency increases in intensity during held, deep inspiration. The murmur may also become higher pitched.This, as well as the location of the murmur, helps to distinguish tricuspid regurgitation from mitral regurgitation.

NOTE: Rivero-Carvallo manouver: With the patient in a seated position, they are requested take a deep inspiration and hold breath (inspiratory apnoea) whilst the examiner listens over the tricuspid area (left lower sternal border)

NOTE: Reversed Rivero-Carvallo sign: Inspiratory reduction in murmur intensity – reported in patients with right sided hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy and straight back syndrome

- José Manuel Rivero Carvallo (1905-1993) was a Mexican cardiologist.

- Rivero-Carvallo JM. Signo para el diagnóstico de las insuficiencias tricuspídeas [A sign for the diagnosis of tricuspid insufficiency]. Arch Inst Cardiol Mex. 1946; 16: 531–540

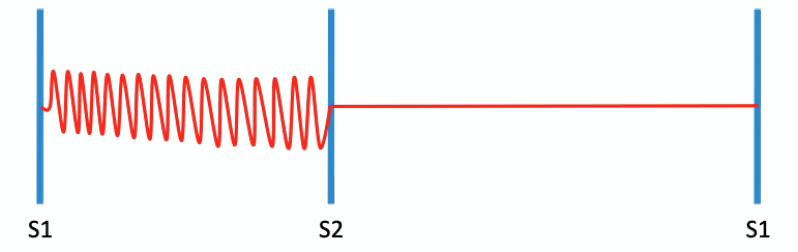

Rytand’s murmur

A blowing diastolic murmur heard occasionally in patients with complete atrioventricular heart block. Best heard at the apex and often confused with mitral stenosis, the murmur is loudest when it appears early in diastole (i.e. when it coincides with the end of the early rapid filling period of the ventricle) but may appear anytime during diastole.

Observations are reported on a blowing apical murmur related to auricular activity in nine elderly but ambulatory patients with varying degrees of auriculoventricular block.…This is another murmur which may be heard at the cardiac apex during diastole in the absence of mitral stenosis.

Rytand DA 1946: 597

- David Abramson Rytand (1909 – 1991) was an American physician and cardiologist

- Rytand DA. An auricular diastolic murmur with heart block in elderly patients. American Heart Journal. 1946; 32: 579-598

Still’s murmur

Benign “twangy” medium-to-long systolic murmur, heard loudest at the left lower sternal border and apex. The cause of Still’s murmur is not well understood. It is thought to be due to the resonance of blood ejected into the aorta, or to the vibration of the chordae tendineae. Most commonly heard in children. Increases in intensity with high output states.

I should like to draw attention to a particular bruit which has somewhat of a musical character, but is neither of sinister omen nor does it indicate endocarditis of any sort. …its characteristic feature is a twangy sound, very like that made by twanging a piece of tense string… Whenever may be its origin, I think it is clearly functional, that is to say, not due to any organic disease of the heart either congenital or acquired.

Still GF. 1909

- Sir George Frederic Still (1868 – 1941) was an English paediatrician.

- Still GF. Common disorders and diseases of childhood. London. 1909. [Still’s murmur 434-435, 481.]

References

- Ma I, Tierney LM. Name that murmur–eponyms for the astute auscultician. N Engl J Med. 2010; 363(22): 2164-8.

- Malik PK, Ahmad M, Rani A, Dwivedi S. The men who picked the truant notes in heart sounds. Astrocyte 2015; 1: 305-8.

eponymythology

the myths behind the names

Doctor in Australia. Keen interest in internal medicine, medical education, and medical history.

U.K trained doctor, medical physician in training.